Now we turn to a phenomenon that arises when the government tries

to fix the price for a product at a level above the

free market price---the problem of surpluses. As an example we

will use the price support program for agriculture that has been

in force in the United States during the past few decades.

We refer here to the market for corn, but the analysis applies

equally well to many other agricultural products.

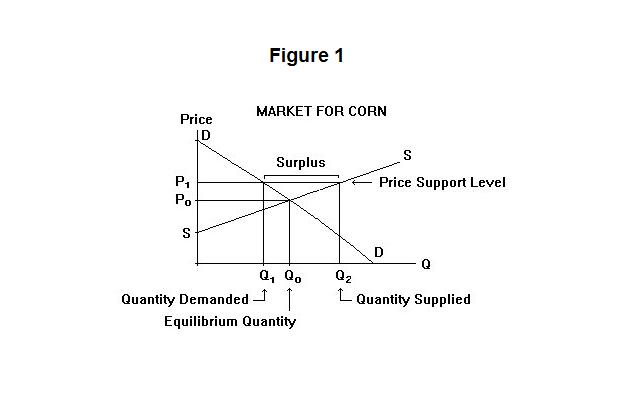

Suppose that the government, under pressure from the farm

lobby, institutes a policy of guaranteeing farmers a price for

corn above the free market price. Let this be the

price P1 in Figure 1. At that price, U.S.

farmers will produce the quantity of corn Q2, but

U.S. buyers (who feed the corn to animals) will chose to buy only the

quantity Q1. The excess

of Q2 over Q1 will represent

a surplus on the market---unless some action is taken to buy up the surplus

(artificially increase demand) or reduce production (control the

supply), the market price will fall back to the equilibrium

level, P0.

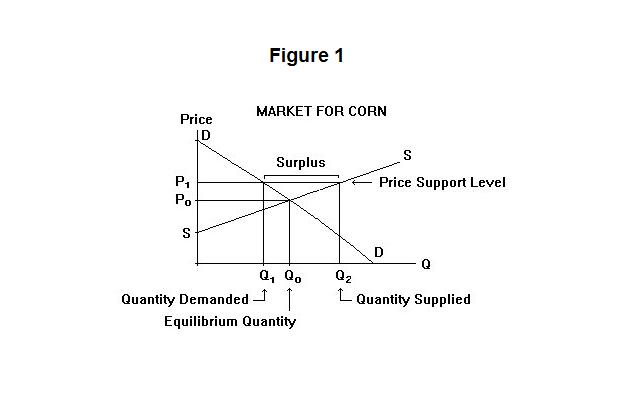

In the initial stages of the program, the U.S. Government maintained the price at P1 by purchasing any surpluses offered at that price. The quantity Q2 minus Q1 was bought up and stored each year in facilities that the Government built. As years passed, these stocks of surplus corn in government storage facilities grew larger and larger, as did the costs of storage.

The government could not dump these surplus stocks on the domestic market or the price would fall below the support level. One option was simply to destroy them. The difficulty with that is the cost to the U.S. tax payer---the annual cost of the price support program would then be P1 (Q2 - Q1) , given as the shaded area in Figure 2, plus the cost of storing the corn temporarily and destroying it. This is, of course, less costly than storing the corn forever.

Common sense would suggest that it would be better to give these surpluses away to poor countries rather than to destroy them. But that is also unpalatable to the taxpayer since the cost would be little different. A somewhat better option from the U.S. point of view would be to dump the surpluses on the international market at the world market price. Unfortunately, this has the effect of lowering that world price and, along with it, the price received corn producers in other countries. They become agitated and pressure their governments into putting restrictions on corn imports from the United States.

We are assuming in Figures 1 and 2 that the United States would not export or import corn under free market conditions---this is not an unreasonable assumption in the case of corn, but it would be entirely inappropriate in the case of products like wheat and cotton. Corn tends to be used locally as feed for livestock. Nevertheless, once prices are artificially raised, imports must be restricted---otherwise U.S. farmers might buy corn from abroad and sell it to the Government under the price support program.

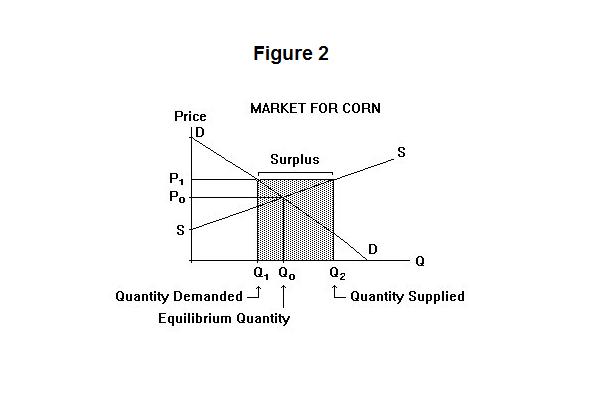

There is good reason to expect that the problem of surpluses will become greater and greater as time passes. For a short period after the price has increased, the supply curve for corn will be quite steep. It takes farmers a while to increase their corn-handling facilities. Then as time passes it becomes flatter as farmers gear up for producing corn. As more time elapses it becomes even flatter as new ways of increasing corn output are devised in response to the higher price. This supply response is shown in Figure 3. It is generally also the case that the demand curve becomes flatter as time elapses after a price change as consumers search out better and better substitutes, but this is not shown in the figure.

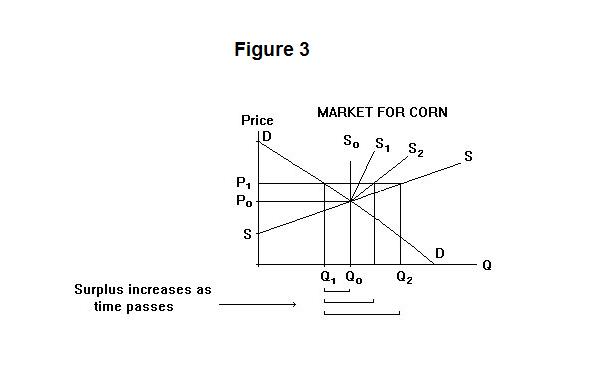

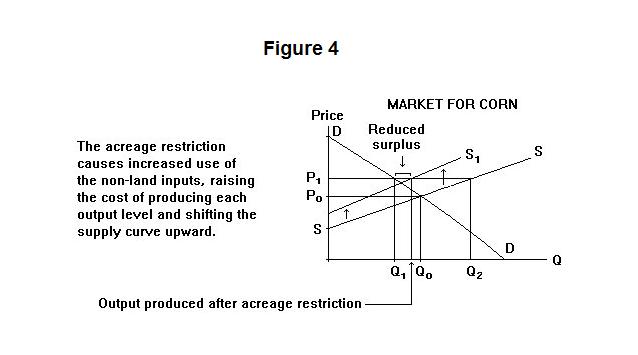

As the costs of the program mounted, the U.S. Government began searching for new ways of getting rid of the surpluses. A policy of acreage restrictions was settled upon. The Government began paying farmers to take land out of production. Since an agreement by farmers to use less land in corn production put no restrictions on the inputs of labor, machine-time, and fertilizer, farmers devoted increasing amounts of these non-land inputs to the restricted acreage. This increased the cost of producing every level of corn output, reducing the output level at which the cost of the last unit produced just equalled the support price. The effect was to shift the supply curve of corn upward as shown in Figure 4.

This had the desired effect of reducing the surpluses, but it did so at the cost of increasing the quantities of labor and capital used to produce every bushel of corn that was in fact produced. This extra labor, capital and fertilizer used to produce the nation's corn output could have been used to produce something else, but people tended not to notice because nothing was actually taken away from them. They did notice the lower tax burden, however, as the surpluses being purchased by the Government became smaller. Thus, the acreage restrictions were politically acceptable to American voters even though the cost of the price support program to the country as a whole may well have increased because of them.

One frequently hears the lament that something is wrong with the economic system when it produces surpluses in one area of the world while people are starving elsewhere. Farmers are especially fond of this argument---what could be better than having the government purchase their output at inflated prices and give it away? Their enthusiasm is a bit hollow, of course, because the generosity is at the expense of someone else. The problem is that the surpluses result from government policies designed to subsidize farmers, not from generosity to starving people abroad. The problem with giving the surpluses to needy people abroad is that someone has to pay for them. Also, giving food might not be the best way of helping poor people in the rest of the world---it might be better to help them improve their capacity to produce their own food.

It is time again for a test. Think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.