We now delve more deeply into the microeconomics

of wage determination and employment. The basic analysis is presented with

reference to the Figure below.

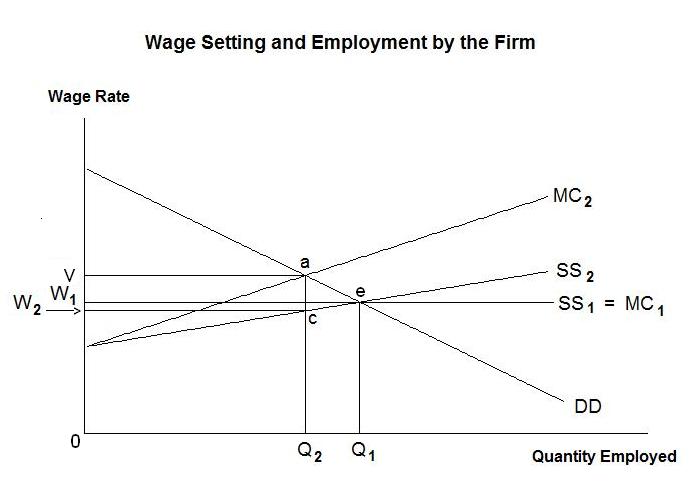

The demand for labour by a specific firm is denoted by the line DD and two

alternative labour supply curves facing the firm are SS1 and

SS2. In the case of the horizontal supply curve SS1,

the firm faces a given market wage for the type of labour it hires with the

result that its marginal cost of labor, given as MC1 , is constant

at the market wage rate W1 . The wage rate that the firm is

willing to pay as the level of employment increases is equal to the value marginal

product of labour, which is equal to the increase in output resulting from the

last unit employed---that is the marginal product of labour---multiplied by the

price at which that last unit of output can be sold, which equals the price of the

product. If the industry is competitive, the product price received by the firm

is also a constant, determined in the market. The value marginal product curve,

represented by the demand curve DD, is downward sloping because as more labour is

hired relative to the other inputs, the marginal product of labour declines. In

a competitive labour market, where the supply of labour to the firm is infinitely

elastic at the market wage, the firm will hire Q1 units of labour

at the wage rate W1 . That output is socially efficient in the

sense that, barring externalities, the value marginal product of labour to society

is the same as the value marginal product of labour to the firm and that value

marginal product is equal to the marginal cost to society of the last unit of

labour employed. If the marginal wage cost to society---that is, the wage rate---is

bigger or smaller than the value marginal product of an additional unit of labour,

it will be socially efficient to decrease or increase the level of employment.

Now consider a situation where the supply of labour to the firm is upward sloping, as indicated by SS2. Under these conditions,the firm has monopsony power in the labour market. Its profits will be maximized where the marginal wage cost, given by the line MC2, is equal to the value marginal product, given as before by the demand for labour line DD. This equality will occur at point a and level of employment Q2. To obtain that quantity of labour, the firm will pay the wage W2 which will be below the value marginal product of labour by the amount a c , yielding an excess profit to the firm equal to the rectangle a c W2 v . The loss in social efficiency will be the triangle a e c . And the workers are "exploited" by the firm by an amount equal to the area W1 e c W2. Keep in mind here that the firm has no monopoly power in the product market---the product price is determined in a market in which the firm sells a tiny fraction of the output.

Under what conditions could the above situation arise? Are firms likely to possess monopsony power in the real world? One can easily imagine such situations---the one-industry town, for example, where most of the town's labour force is employed by one large multi-national firm. For this firm's monopsony power to be sufficient to result in substantially lower wages, however, workers would have to be unwilling or unable to move elsewhere to improve their lot---if workers are able to migrate but chose not to, the monopsony firm is capturing economic rents workers obtain by living in a place they love.

Another easily imaginable monopsony situation is where a particular firm employs, among its workers, a particular type of worker endowed with firm-specific human capital skills that are not anywhere else demanded. It might be presumed that in this specific human capital market the firm faces a near vertical supply curve of labour whereby, there being an enormous distance between a and c in a Figure like the one above, it's profit maximizing equilibrium is to pay these workers very low wages relative to what would be received by workers with a similar level but different type of human capital. A bit of thought will suggest, however, that by paying low wages this firm will destroy its reputation as an employer of skilled workers---potential skilled employees will demand higher wages than they could earn elsewhere to compensate for the probability that, once they have acquired skills specific to the firm, the firm will exploit them.

A similar situation could arise with more senior workers who do not merit promotion to very high-paying administrative position but are nevertheless competent in the jobs they do and, given their age, have few opportunities elsewhere. Can the firm maximize its profit by exploiting these workers, paying them less than recently hired younger workers with the same skills? The answer again is that the firm will want to maximize its long-run profits rather than the profits in any particular year. In order to hire high quality young workers at going wages, a firm has to be able to demonstrate that the firm would be a good place to work over a worker's entire life, not just for a few years when that worker is young.

Accordingly, the firm like the one portrayed in the Figure above may be better off paying a wage rate above W2 when the diagram applies to profit maximization in only the current year because, if the usual span of employment is the worker's lifetime and the wage rate is a lifetime wage, the firm really faces a flat labour supply curve such as SS1.

It is now time for a test. As always, think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided. The second and third questions explore issues which, though not directly covered in this Topic, you should be able to analyse given what you have learned in this and the previous two Lessons.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson