In concluding this Lesson we want to summarize what economists can

and cannot say about institutional arrangements and government policies

designed to improve the economic welfare of society. We have already

noted that economists can give very useful guidance to society on matters

of efficiency, but their value judgements on matters of distribution are

no better than anyone else's.

When economists say that a particular government policy or

an institutional change (that is, change in the rules according

to which people do business with each other) leads to a gain in

efficiency they mean something very specific. They mean that

under the new arrangement it would be possible to make everyone

better off. That is, the gainers could compensate the losers

and still have something left over. Once such efficiency gains

have been fully exploited and a situation has been reached where

no further efficiency gains are possible---where one person's

situation can only be improved by making someone else worse

off---we say that the allocation of resources in the economy is

Pareto Optimal or Pareto Efficient.

The concept is named after Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923).

The production and consumption of the various goods in the

economy is Pareto Optimal when the combined rents to producers

and consumers are the largest that can be obtained. Since these

optimal quantities produced and consumed depend on the positions

of the demand curves for the various goods, and since the demand

curve for any good depends on the distribution of income between

those who like the good a lot and those who do not, changes in

the distribution of income will affect the demand curves for the

various commodities and the maximum consumer and producer rents

that can be obtained by producing and consuming them. The

Pareto-Efficient production and consumption levels for the commodities

produced and consumed in the economy will thus depend on the

distribution of income---the fact that a situation is

Pareto Optimal therefore does not imply that the distribution of

income at which it arises is a socially desirable one.

We have established that an important requirement for the usefulness of

straight-forward supply and demand analysis is that products be

competitively priced. By this we mean that each individual

buyer and seller buys such a small portion of the total quantity

of the good that his/her actions cannot appreciably influence

the market supply or demand---hence each market participant takes

the price as given. Economists call this perfect competition.

If there are no externalities, then competitive pricing implies

that the Pareto-Efficient quantity will be the one at which the

supply and demand curves intersect. These are the quantities

that will maximize combined producer and consumer rents for the

particular distribution of income that leads to these supply and

demand curves.

This condition that in the absence of externalities perfect

competition will lead to Pareto Optimality is called the first

theorem of welfare economics. While the ideas behind this

theorem have been known for decades, it was made precise by

Kenneth Arrow (1921- ), and Gerard Debreu (1921-2004). Note again

that this is a theorem about efficiency, not social welfare

in general. There are many possible competitive equilibria

since every different distribution of income will have associated with

it a different Pareto-Efficient mix of goods produced and consumed.

Economic efficiency involves getting to one such equilibrium---choosing

an appropriate distribution of income and thereby picking the particular

Pareto-Efficient equilibrium that will be the socially desirable one involves

value judgments and goes beyond the scope of economic analysis.

A movement to Pareto Optimality without the gainers

compensating the losers involves a redistribution of income.

The new equilibrium is still a Pareto-Efficient one in the sense

that, the redistribution having been made, it is now impossible

for any individual to gain without someone else losing. Because

of the distribution effects from moving to a Pareto-Efficient

situation, the losers will frequently engage in rent seeking to

prevent such a move from taking place.

If there are no transaction costs involved in making and

enforcing agreements among individuals and groups of individuals

and if the individual rights of all transacting parties are

properly guaranteed by the legal system, then the gainers would

bribe the losers to obtain their agreement and Pareto-Efficiency

would occur naturally. This notion that Pareto-Efficiency will occur

automatically if transactions costs are zero and gainers can always

compensate losers is called the Coase Theorem (due to

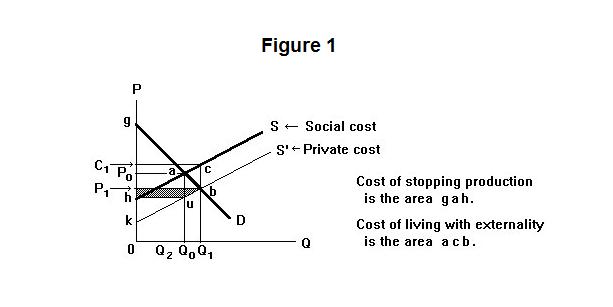

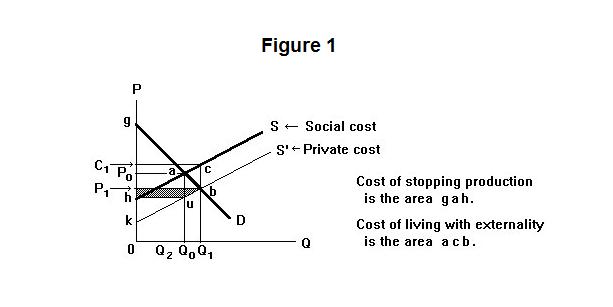

Ronald Coase (1910- ). It can be illustrated with respect to the familiar

externality arising from industrial smoke. The argument is

presented in Figure 1. We suppose for simplicity that the

social cost of production including the environmental damage

from the smoke by-product is the curve h S while the cost

of production of the industry, which pays none of the cost of

the smoke damage, is k S'. We also assume for simplicity

that smoke inhibiting devices are prohibitively costly. The

demand for the product is g D. We assume that the adverse

effects of environmental damage are borne by conumers alone.

Suppose now that the system of property rights protects

consumers from industrial smoke---no one has a right to produce

smoke without explicit permission from those affected. In the

absence of such permission the output of the product will be zero.

When there are no transactions costs, however, producers can easily

obtain the consent of consumers---they can agree to pay them the

amount h a u k for the right to

produce the quantity Q0 and sell it at the

price P0. Consumers will capture the

area g a P0 and producers will capture

the rent P0 a h. Bargaining between

producers and consumers could lead to a different split of the

rent g a h than this, but whatever

the distribution of these gains, the Pareto-Efficient output will

be produced.

Alternatively, suppose that well-defined property rights

exist that place no restrictions on industrial smoke. The

industry will produce the output Q1 and the market price

for the product will be P1. Producers will earn a

rent, over and above the private opportunity costs, equal to the

area P1 b k. Consumers will earn the

surplus g b P1 minus the cost to them

of the smoke damage, given by the

area h c b k. Taking everything into

consideration, the economic rent to society will be the

area g a h minus the

area a c b. This falls short of the maximum

possible rent by the area a c b, which equals

the area g b P1 plus the area

P1 b k minus the

area h c b k.

When there are no transactions costs, consumers will form an association and agree to pay producers an amount sufficient to induce them to produce the output Q0 and sell it at the price P0, rebating their profits, P0 a u h, back to the consumers' association for distribution to its members. Producers will require a payment from consumers equal to the shaded area to compensate them for the loss of rent from producing Q0 rather than Q1. Given linear supply curves, this shaded area is equivalent to the area C1 c a P0.

Since the price P0 now reflects consumers' full costs, including the environmental costs, they directly lose the area P0 a b P1 as compared to their previous situation. Previously they were receiving the consumer surplus g b P1 minus the environmental costs h c b k. Given linear supply curves, these environmental costs can be equivalently represented by C1 c b P1, so that the previous net benefits to consumers could be alternatively represented as g b P1 minus C1 c b P1.

After bribing producers to get them to produce Q0 at a net price u Q0, consumers lose, as they move from Q1 to Q0, the amount they have to compensate producers C1 c a P0 ( which is equivalent to the shaded area ) plus a reduction P0 a b P1 in consumer surplus. In doing this they avoid the loss C1c b P1 (which is equivalent to h c b k) leaving them with a net gain equal to the area a c b. The direct loss of consumer surplus plus the bribe to producers is less than the costs of the pollution by this area. Some of this gain will have to be shared with producers to obtain their agreement by making them better off rather than indifferent between the new and old arrangements.

When there are no transactions costs the inefficiencies resulting from price collusion among firms will also disappear, even if collusive agreements are enforceable in the courts. Consumers will simply pay cartels slightly more than the amount of their profits from collusion in return for their agreement to price competitively.

Given zero transactions costs, Pareto-Optimality will be attained as long as the government allows people to make the necessary agreements. The distribution of income will depend on the initial property rights before these agreements take place. But no matter what the initial situation, agreement will take place and Pareto-Optimality will be achieved as long as property rights are clearly defined and enforced.

The problem is, of course, that transactions costs are not zero. One or two firms may agree on a strategy, but it will be impossible to get a large number of consumers to agree on the payment or compensation for each consumer. There will always be hold-outs who will try to obtain a greater share of the rents. As a result, the Coase Theorem will not be applicable to most situations---the importance of the theorem is in its delineation of the appropriate roles of transactions costs and property rights in the achievement of Pareto-Efficiency. Property rights are important because individuals cannot make agreements unless they have the legal right to do so and any such agreements are legally enforceable. The particular property rights established in any situation also determine the distribution of income.

Because transactions costs are often large, Pareto-Efficient outcomes frequently cannot be achieved by private transactions. The government can often produce a Pareto-Optimal situation by intervening---for example, the optimal degree of pollution in Figure 1 can be engineered by putting a per-unit tax on output equal to a u. The trouble is that transactions costs of handling social problems through government are also not zero. Producers will lobby against the tax. Environmental groups will lobby in favor of it. The policies of the government will most often be determined by the effectiveness of the rent-seeking activities of the gainers and losers from government action---this will be determined, in turn, by whether transactions costs are lower for the gainers or for the losers.

It is again time for a test. Think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.