Central banks in big countries can invoke tight (or easy) money by reducing

(or increasing) the stock of base money sufficiently to raise (or lower) the

real interest rate above (or below) its full-employment level.

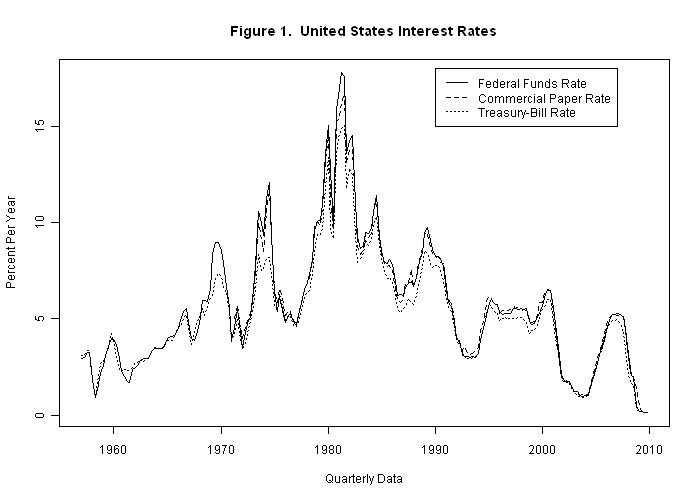

For the United States, the federal funds rate

is a good indication of the level of short-term interest rates. The job

of the Federal Reserve System is to vary the money supply so as to adjust

this rate to the desired level. Since the banking system holds other

assets in addition to reserves, it will bid the federal funds rate into

line with other interest rates in the economy. Appropriate money supply

adjustments will thus lead to changes the nominal interest rates in

the U.S. economy to appropriate levels and, given the expected inflation

rate, real interest rates will also be adjusted appropriately. The movements

of nominal interest rates in the United States during the past half-century

are evident from Figure 1 below.

Short-term interest rates clearly moved rather closely together. The commercial paper rate increases above the treasury bill rate during periods of high inflation because it is a more risky asset in boom periods---default of private firms is clearly more likely than government default in the periods of decline that will typically follow. And the federal funds rate follows the commercial paper rate more closely than it follows the treasury bill rate since commercial banks are private rather than government institutions.

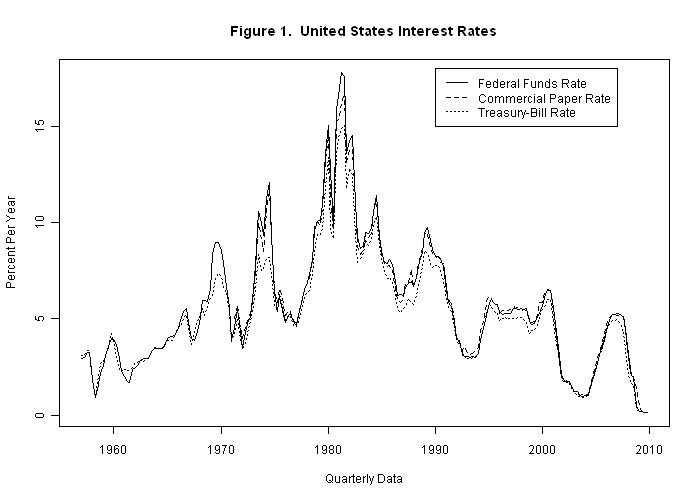

Since the federal funds rate is determined in a market, manipulation of that rate by the authorities presents a problem in that they will have difficulty determining whether a particular movement in the rate was a result of their actions or a consequence of market forces---they can never be sure exactly how much of an observed change was policy-induced. Moreover, quite aside from this problem, high nominal interest rates do not necessarily imply that money is tight---it may merely indicate that the expected future inflation rate is high. As can be seen from Figure 2 below, the federal funds rate, and hence other interest rates, tend to move with the inflation rate and tend to be above the inflation rate, reflecting the fact that realized real interest rates typically tend to be positive.

Actual interest rate movements depend on changes in expected as opposed to actual inflation rates and the former are not observed. This was reflected in the fact that during the inflationary period between 1965 and 1980 the U.S. authorities thought that money was tight when it was in fact easy.

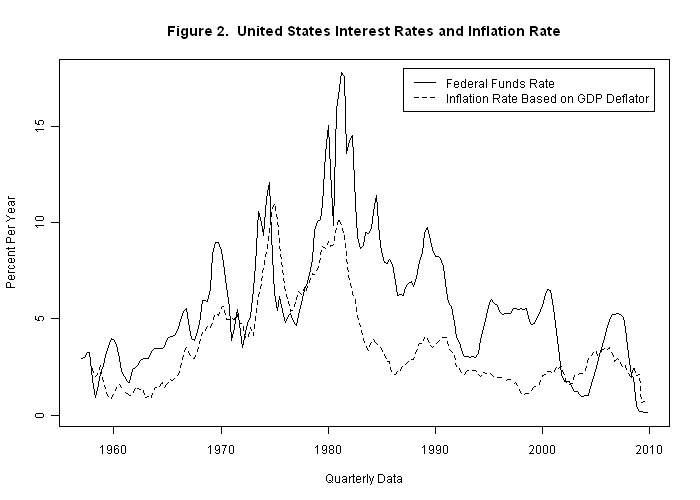

A potential way around this problem was devised by John Taylor (1946- ). He suggested that the federal funds rate be set according to an equation like

TRFFR = INFR + 2.0 + 0.5 ( INFR - 2.0 ) - 0.5 ( UEMR - 6.0 )

where TRFFR is the level the federal funds rate should be set at according to the Taylor Rule, and INFR and UEMR are the inflation and unemployment rates. This formulation of the rule assumed that the desired inflation rate and the real interest rate are both equal to 2 percent and the normal level of unemployment is 6 percent---the actual formula used in a particular case can be adjusted to reflect different magnitudes of these variables.

As is clear from Figure 3 below, this Taylor Rule confirms that monetary policy was easier in the inflationary period before 1980 than it should have been. It also suggests that monetary policy was tighter than it should have been during the 1980s.

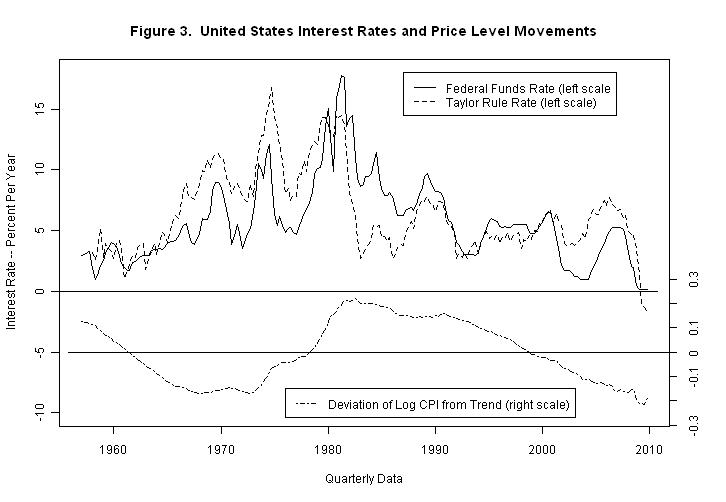

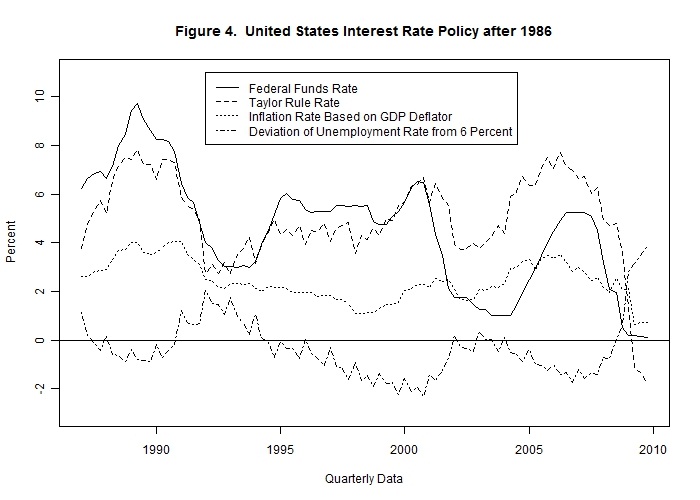

The above data and additional relevant series are plotted for the shorter period 1987-2009 in Figure 4 below.

The federal funds rate followed the Taylor Rule reasonably closely between for the period 1987 through 2001. Thereafter, until 2009 the Federal Reserve System conducted substantially more expansionary monetary policy than suggested by the Taylor Rule. The situation became sufficiently bad in the crises in 2009 that the Taylor Rule suggested a negative value for the federal funds rate---this is at a time when that rate is less than 1/4 of one percent with an inflation rate of less than 1 percent per year, calculated using the GDP deflator. At the end of 2009 the unemployment rate is close to 10 percent.

It is sometimes argued that interest rates close to zero present a problem for the implementation of monetary policy. This is true only to the extent that monetary policy focuses exclusively on interest rates. A zero interest rate presents no obstacle to monetary expansion---the central bank can increase the money supply simply by purchasing assets from the private sector. There is clearly some maximum money supply that the public will be willing to hold. Even if the interest rate on treasury bills is virtually zero it still makes sense for holders of excess money balances to purchase real assets---such assets will always yield a positive real return if the capital stock is productive. And, alternatively, consumer durables or even non-durables can be purchased with money balances in excess of those needed to make exchange.

Obviously, the exercise of monetary policy requires judgment! Mathematical models and formulas may be helpful in forming appropriate judgments but they are clearly insufficient in and of themselves. To take a further example, note that the Taylor Rule is devised from a closed economy perspective, implying no change in the real exchange rate consequent on monetary expansion or contraction. Unless foreign countries maintain their exchange rates with the U.S. dollar fixed, a U.S. monetary expansion will lead to a decline in that country's real exchange rate with respect to the rest of the world. This will shift demand onto U.S. output off foreign output resulting in a greater output and employment expansion in response to any given fall in the U.S. federal funds rate. The Federal Reserve authorities must therefore make a judgment regarding any exchange rate effects of monetary policy in each particular instance. Also, there is the question of how long it will take for policy changes to impact domestic output, employment and prices---the magnitude and timing of the effects of each policy initiative will depend critically on these issues.

It should be clear from the material presented in previous modules that a Taylor Rule makes no sense at all for countries that are too small to be able to influence world interest rates. Take Canada as an example. Canadian and United States treasury bills both have essentially zero default risk. The only difference between their ex-post yields is differential changes in the two countries' inflation rates. And the only difference between their ex-ante yields is expected differences in those inflation rates. The same is true of all other Canada/U.S. interest rate differentials once one adjusts for risk. The magnitudes of changes in the demand for Canadian assets as a result of expansionary monetary policy by the Bank of Canada will equal tiny fractions of the overall portfolios of asset holders abroad. It is therefore difficult to see how their estimates of the differential risks of holding Canadian assets would be much affected by changes in the quantities of these assets demanded by Canadians resulting from their portfolio responses to money supply changes. Indeed, it has already been clearly demonstrated that monetary policies in small open economies operate through their effects on exchange rates rather than interest rates.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.