We now turn to an analysis of alternative small-country

responses to real shocks occurring in the big country. Real shocks

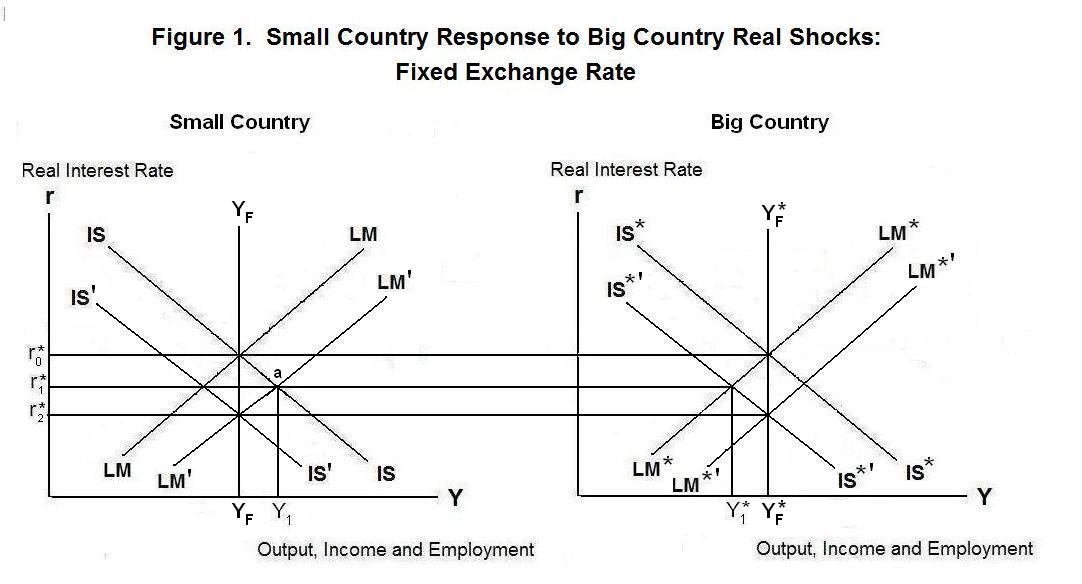

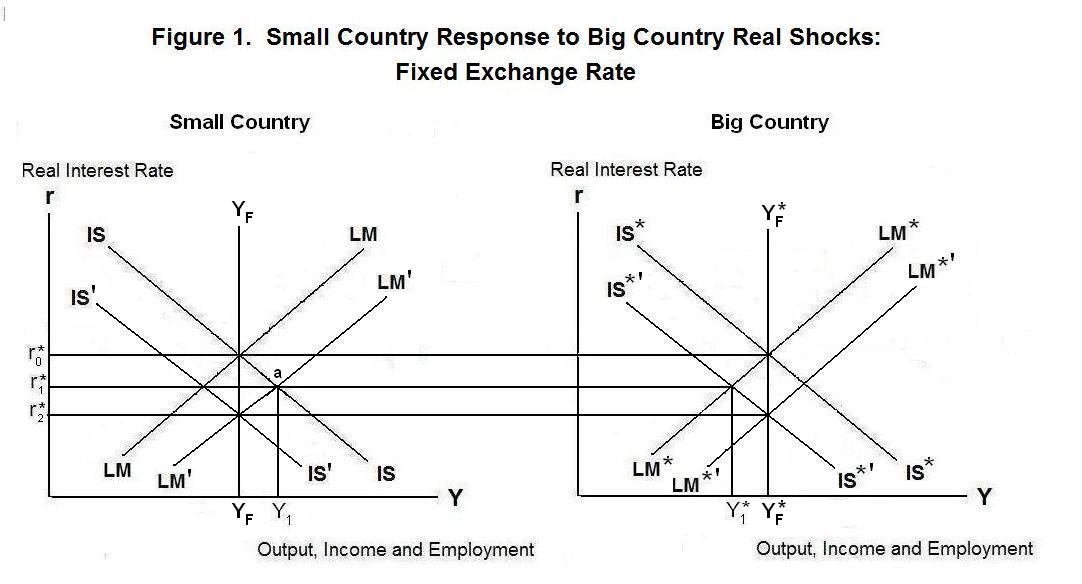

involve a shift in the big country's IS curve. An adverse real

shock is shown in Figure 1. This could arise as a result of tight

fiscal policy, an exogenous decline in consumption, or an exogenous

decline in investment. The result is a fall in the world real interest

rate to r1* . To keep the argument simple we will

assume that the small country experiences no real shock, so that

its IS curve is initially unaffected.

The task at hand is now to show how the small country's authorities might react to this change in the world real interest rate. First they have to decide whether to fix the exchange rate or let it float. If they adopt a flexible exchange rate they then have to decide upon an appropriate monetary policy.

Suppose that the central bank fixes the exchange rate. Then equilibrium will be determined by the intersection of IS and the real interest rate line. Output will rise to Y1 in the small country while at the same time falling to Y1* in the big country.

Notice that when the exchange rate is fixed output moves in opposite directions in the two countries in the short run in response to a big-country real shock. This is in contrast with big-country monetary shocks, which cause the two countries' outputs to move in the same direction in the short run under fixed exchange rates. The increase in income in the small country will cause its residents to hold a larger stock of money. They will acquire these additional money holdings by selling non-monetary assets to big-country residents. The central bank, to keep the currency from appreciating, is forced to accumulate foreign exchange reserves, putting the necessary additions to the money stock in circulation in the process. This will shift LM to the right to pass through point a.

In the long run, when wages and prices are flexible, the price level in the big country will fall, driving LM* down to LM*' , at which point output and income in the big-country will have returned to the full-employment level. This will drive the world interest rate down further to r2* . The fall in the big-country's price level will increase the small country's real exchange rate at the fixed level of the nominal exchange rate and at any given domestic price level. Ultimately, the real exchange rate must appreciate sufficiently to drive IS to IS' so it will cross through the intersection of the YF line and the real interest rate line. The return of income to YF will reduce the quantity of money demanded by the small country's residents. At the same time, the decline in the real interest rate will increase their quantity of money demanded. The figure is drawn so that these two effects offset each other exactly with no net effect on portfolio equilibrium. Thus, no further change in the stock of official foreign exchange reserves or the stock of nominal money holdings will occur as long-run equilibrium is established provided that the domestic price level does not change.

What will happen to the domestic price level? We can't say for sure because the real exchange rate appreciates while the nominal exchange rate is constant and the foreign price level falls. From the definition of the real exchange rate,

Q = P / Π P* ,

where Q is the real exchange rate, P and P* are the price levels and Π is the nominal exchange rate, defined as the price of the big country's currency in terms of the small country's currency, we can see that the ultimate movement of domestic price level could be in either direction, depending upon whether the real exchange rate appreciates by more or less than the foreign price level falls. This will depend on responsiveness of the small country's trade balance to real exchange rate movements. Clearly, however, the small country's price level will move by less than the movement of the price level in the big country. This suggests that by maintaining the fixed exchange rate the small country neutralizes at least some of the effects of big-country real shocks on its price level in the long run. But, of course, the short-run output effects on the small country are opposite to those in the big-country.

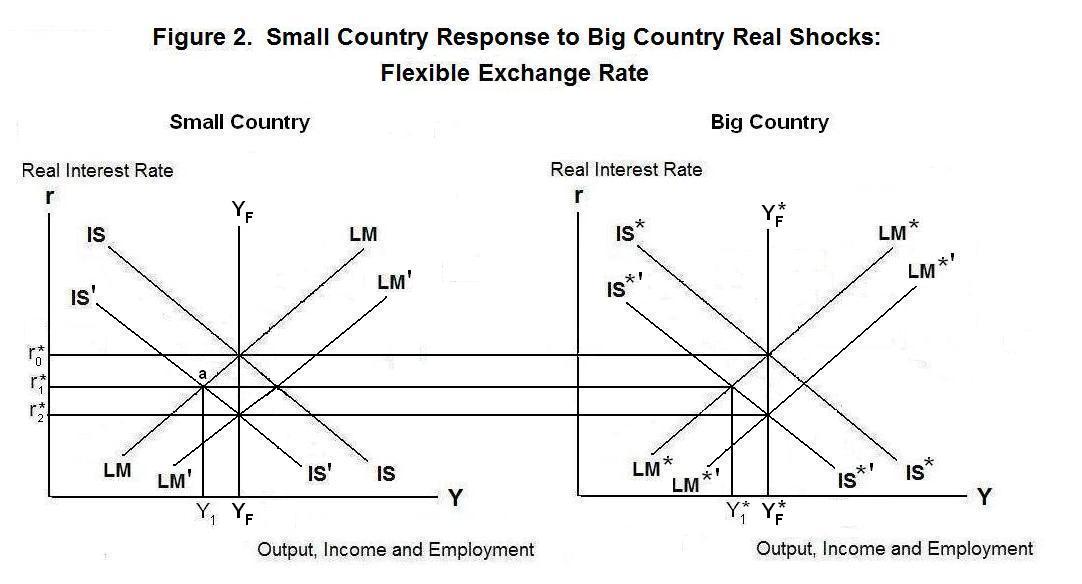

Now suppose that the small country lets the exchange rate float and holds its money supply constant. The effects of the big country real shock on the small country in this case are shown in Figure 2. The fall in the world interest rate in the short-run causes output to fall to Y1 since equilibrium is now determined by the intersection of LM and the real interest rate line---this occurs at point a. Note that under a flexible exchange rate with a constant money supply, the income and output effects in the big-country are transmitted directly to income and output in the small country.

As long as the IS curve crosses the real interest rate line to the right of point a, there will be upward pressure on income and on the demand for money. This will cause domestic residents to try to sell assets abroad for money, creating an incipient balance of payments surplus and causing the small country's currency to appreciate. This will happen until IS has shifted to the left to IS' .

In the long run when the price level in the big country falls and the world real interest rate moves down to r2* , there will be equivalent downward pressure on the small country's price level. The domestic price level will have to fall until LM has shifted to the right to LM' . If the big and small country are structurally the same except for size, we would expect the their price levels to fall in the same proportion. The entire adjustment of the real exchange rate required to shift IS to IS' will then fall on the nominal exchange rate. This can be seen from the definition of the real exchange rate,

Q = P / Π P* .

Notice that under a flexible exchange rate with a constant money supply in the long run, effect of the shock on the big country's price level is transmitted directly to the price level of the small country.

The small country's central bank can manage the float to keep the domestic price level from falling. It simply increases the money stock sufficiently to shift LM to LM' at the given pre-shock domestic price level. This will mean that real exchange rate adjustment required to move IS to IS' will not necessarily involve an appreciation of the nominal exchange rate. This will depend upon whether the fall in P* is sufficient, at the unchanged level of P , to bring about the required appreciation of the real exchange rate.

The effect on the nominal exchange rate will be ambiguous for the same reason as the effect on the domestic price level was ambiguous in the fixed exchange rate case. This can be seen by looking again at the definition of the real exchange rate.

Q = P / Π P* .

P* falls and Q rises, with P unchanged. Thus, Π will rise (fall) if P* falls proportionally more (less) than Q rises. This will depend on the amount the IS curve shifts in response to a given change in the real exchange rate.

It's time for a test. Be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Question 4

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.