Shocks in the big country can be divided into two types,

real or monetary, according to whether the shock affects the IS

curve or the LM curve. This topic deals with the small

country's response to big-country monetary shocks. Its response to real

shocks in the big country is the focus of the next topic.

Suppose that there is a positive monetary shock in the big

country that results in a rightward shift of its LM curve. This

shock could arise from an increase in the supply of money or a

reduction in the demand for money. Let us begin by assuming that the small

country adopts a fixed exchange rate. The big country, of course, does not

care about the exchange rate since it is unaffected by small-country

exchange rate decisions.

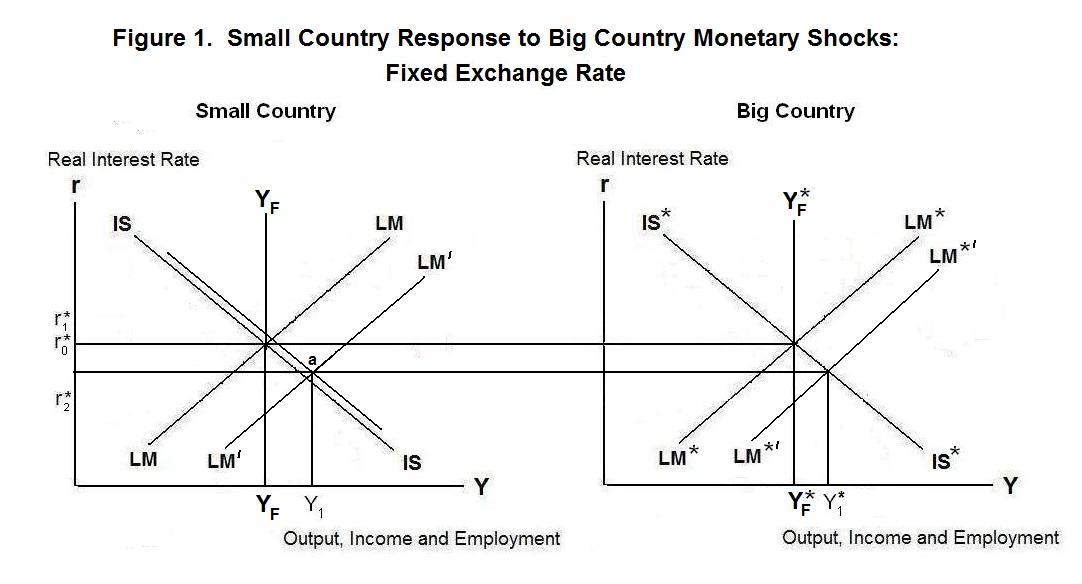

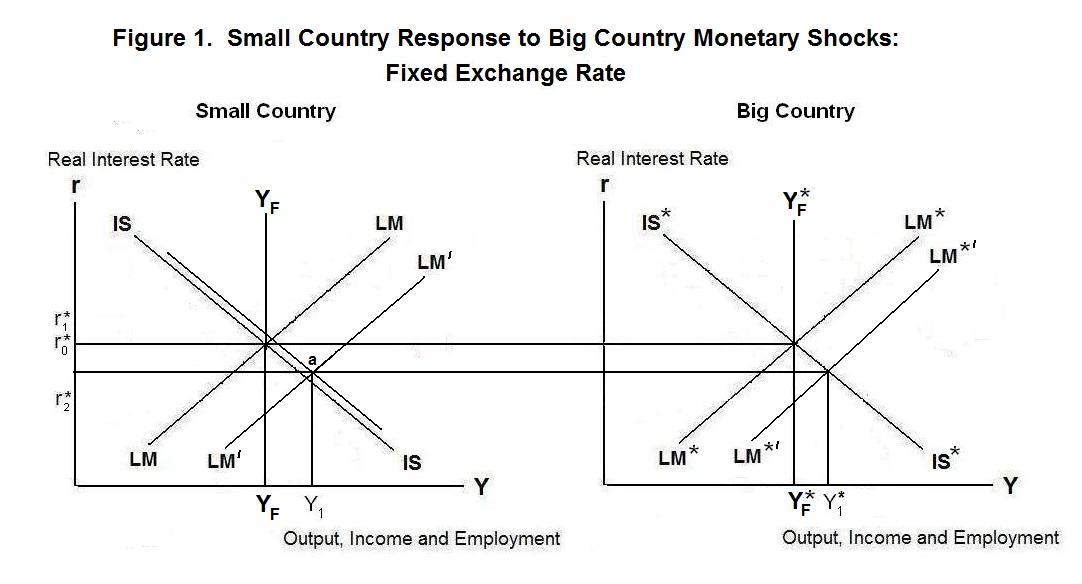

The situation is shown in Figure 1. The positive monetary

shock in the big country causes the world interest rate to fall

to r1* and the level of income and employment in

the big country to increase. As this increases the small country's exports,

its IS curve will shift to the right. Under the fixed exchange

rate regime, income in the small country is determined by the intersection

of IS and the world real interest rate line, so income will

increase to the level indicated by point a . This will cause

domestic residents to hold additional money balances, which they

will obtain by selling assets abroad. To keep the currency from

appreciating the small country's central bank must accumulate

foreign exchange reserves, putting domestic money in circulation

in the process. This endogenous increase in the money supply

will shift LM to the right to LM' .

You should now fully understand that policy and other shocks

in the big country have important effects on the small country

that operate primarily but not exclusively through changes in the

world real interest rate, while the effects of shocks in the

small country on the big country are insignificant and can thus

be ignored. We now turn to a consideration of how the small

country can respond to big-country shocks, and of the implications

for its employment, income and prices of alternative responses.

Ultimately, the response must take the form of a decision to

adopt a either a fixed or flexible exchange rate and, if the latter

is chosen, a decision as to what kind of monetary policy to follow.

In the long run, when wages and prices are flexible, the price level in the big country will rise, reducing the real quantity of money and shifting LM* back to its original position. This will return the world real interest rate and foreign output to r0* and YF* in Figure 1 and, since the increase in small-country exports to the big country will be eliminated, the small country's IS curve will return to its original position. When the exchange rate is fixed the rise in the world real interest rate will reduce the small country's output and income back to YF . This will return the demand for real money balances to its original level as full employment is reestablished.

The new equilibrium involves the same income and interest rate levels and the same IS curve as the original pre-shock equilibrium so the real exchange rate must ultimately return to its pre-shock level. Since the nominal exchange rate is fixed, the small country's price level must rise in proportion to the big country's price level. This follows from the definition of the real exchange rate,

Q = P / Π P* ,

where Q is the real exchange rate, P and P* are the price levels and Π is the nominal exchange rate, defined as the price of the big country's currency in terms of the small country's currency. To maintain the fixed exchange rate, the authorities will have to buy or sell foreign exchange reserves in return for domestic currency to ensure that the domestic nominal money stock rises in proportion to the domestic price level.

The important thing to note here is that when the exchange rate is fixed big-country monetary shocks have the same effects in both countries in both the short and long runs.

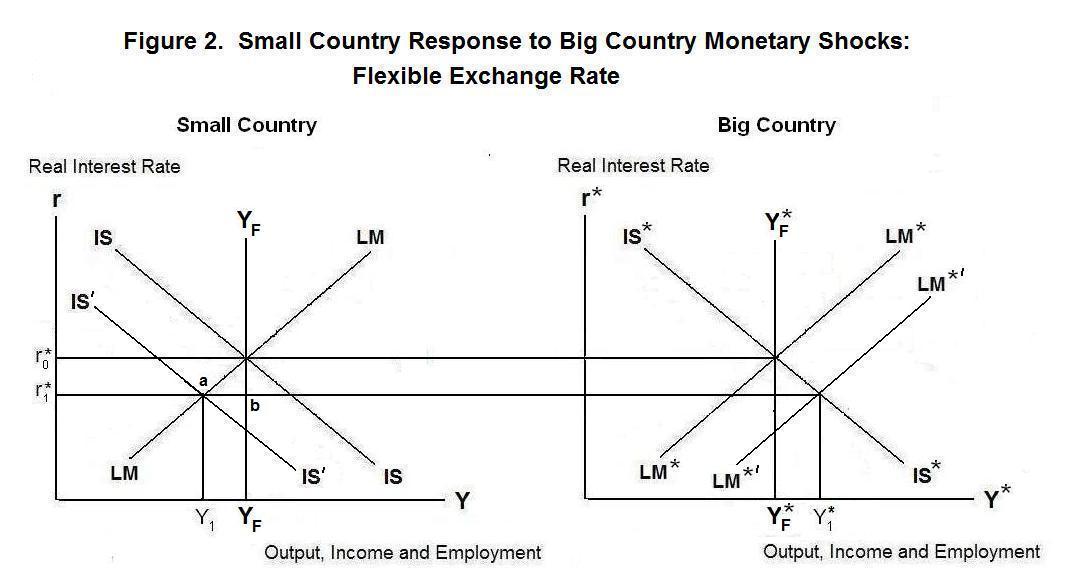

When the small country lets the exchange rate float and and holds the domestic money supply constant, the short-run effects are the opposite to those under a fixed exchange rate. This is shown in Figure 2. Equilibrium is now determined by the intersection of the LM curve and the world real interest rate line. The fall in the world interest rate increases the desired money holdings of the small country's residents, causing them to try to sell non-monetary assets abroad to accumulate money. This results in an incipient balance of payments surplus which causes the domestic currency to appreciate until the IS curve has shifted to the left to IS' . Income falls, with the new short-run equilibrium occurring at point a .

Note that income in the small country moves in the opposite direction to income in the big country. The small country's central bank could prevent the decline in domestic income by increasing the money supply sufficiently to shift LM rightward to intersect the real interest rate line at the full-employment output level---at point b . This would reduce the required appreciation of the nominal and real exchange rates, making the leftward shift of IS smaller so that it too would pass through point b .

In the long run when the exchange rate is flexible, the return of the world interest rate to r0* will mean that the IS curve must return to its original level in Figure 2, equilibrium being determined by the intersection of LM and the world interest rate line. This means that the real exchange rate must return to its original level, depreciating by the same amount as it had appreciated in the short run. As the price level in the big country rises at given levels of domestic prices this depreciation will occur naturally without necessitating a further change in the nominal exchange rate.

Remember again that

Q = P / Π P* .

The domestic price level will not change since the LM curve does not shift---nothing happens in the long run to affect either the demand or supply of money in the small country. Since Q returns to its pre-shock level along with the IS curve and P remains constant while P* rises, Π must end up lower than its pre-shock level in the same proportion as P* is higher. The flexible exchange rate insulates the small country's economy from the big country's monetary shock in the long run, though not in the short run.

In the case where the small country's central bank increases the money supply to maintain income equal to YF , shifting LM to the right to pass through point b , this monetary expansion will have to be reversed as the world interest rate rises. Otherwise the domestic price level will rise in the long run. The LM curve must return to its original position, either as a result of a return of the nominal money stock to its initial level or through an appropriate rise in the small country's price level.

When the small country's authorities vary the money supply to maintain domestic income constant in the face of shocks from abroad they are adopting a regime of managed floating instead of a pure flexible exchange rate regime. The idea is to conduct discretionary policy to offset shocks to the domestic economy. This is extremely difficult to do, because the small country's authorities have to be able to determine what kinds of shocks are occurring and to correctly gauge their magnitude. Then they also have to know the time path of the response of the domestic economy to their policy actions.

It's time for a test. As always, think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.