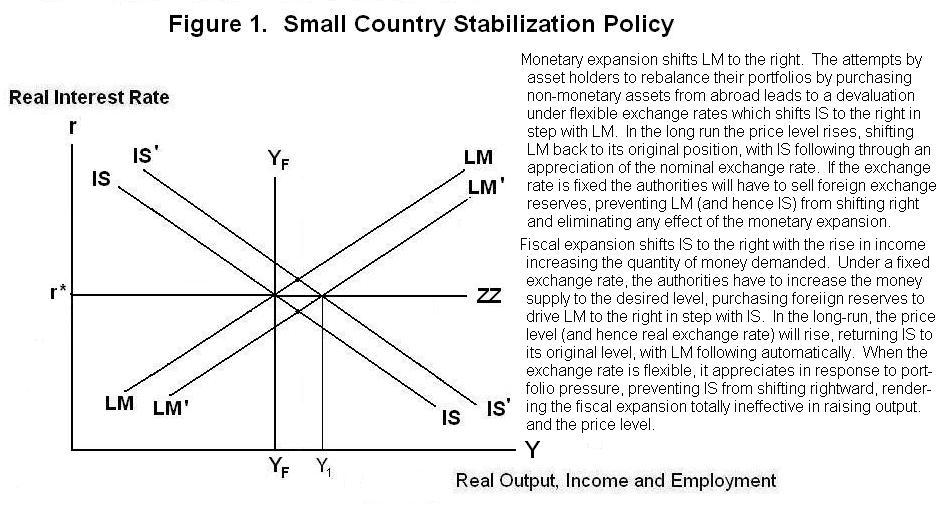

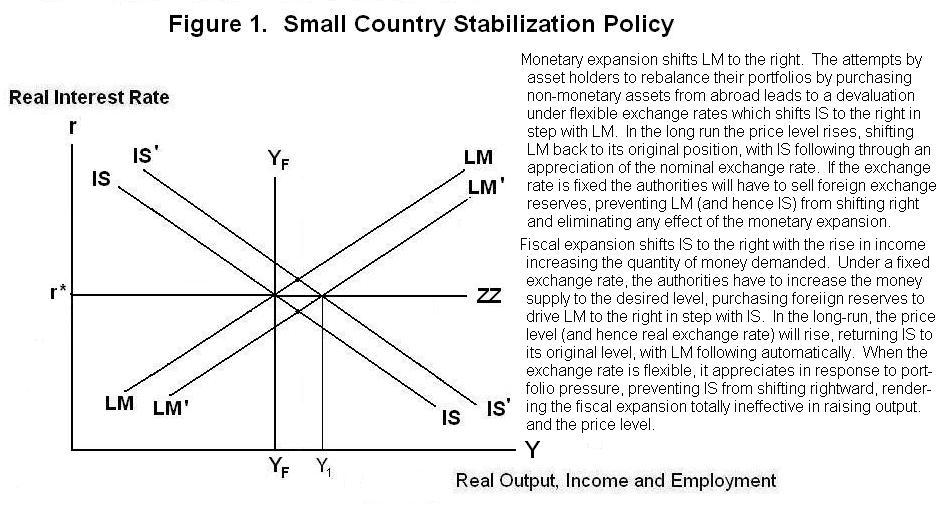

The effects of policy shocks in the small country will

depend on whether the exchange rate is fixed or flexible. Both

cases are examined in Figure 1. In the flexible exchange rate

case, it will be recalled, equilibrium is determined by the

intersection of the LM curve and the world interest rate line,

here labelled ZZ to conform to our exposition in earlier lessons.

An increase in the nominal money supply shifts LM to the right,

say to LM'. Faced with excess money holdings, people re-establish

portfolio equilibrium by purchasing assets abroad. This creates

an incipient balance of payments surplus which is eliminated by a

devaluation of the domestic currency. The devaluation shifts the

IS curve to the right until it passes through the

new LM-ZZ intersection. Output increases above the

full-employment level---which can be thought of as the normal or natural

level---to Y1.

We now turn to an examination of the effects of monetary,

fiscal and other policies in the big and small countries on their

own economies. For the small country, this is largely a review of

material covered in previous lessons. For the big economy we are

breaking new ground. Consider the small country first. Since the

world real interest rate can be taken as constant, given by

the situation in the big country which is unchanged by construction,

we need consider only small country's equilibrium, focusing

entirely on the left panels of figures like those presented in

the previous topic.

As time passes, wages and prices will rise in response to the abnormally high level of employment. This will shift LM back to its original position and output will return to its full-employment level. The nominal exchange rate will adjust to ensure that the real exchange rate returns to its initial level. This will imply an ultimate depreciation of the domestic currency, as compared to its pre-shock level, in the same proportion as the increase in the price level.

A fiscal expansion will lead to a rightward shift of the IS curve subject to the qualifications noted in the lesson entitled Fiscal Policy. This will tend to increase output and the demand for money. When the exchange rate is flexible, however, the attempt by asset holders to rebalance their portfolios by selling non-monetary assets abroad in return for money will create an incipient balance of payments surplus, causing the country's currency to appreciate. This will shift IS back to the left until any increase in income has been eliminated. Fiscal policy is thus impotent under flexible exchange rates. Tariff increases and export subsidies---that is, commercial policies---will have results identical to those of fiscal expansions under flexible exchange rates.

When the exchange rate is fixed, equilibrium is determined by the intersection of the IS curve with the ZZ line as shown in Figure 1, and the central bank is forced to supply whatever quantity of money the public wishes to hold. A monetary expansion will put rightward pressure on the LM curve, causing people to unload these excess money holdings by purchasing non-monetary assets from big-country residents and thereby creating a balance of payments deficit. The central bank will have to sell foreign exchange reserves in return for domestic currency to keep the domestic currency from depreciating. This will keep money holdings at their equilibrium level and maintain the continuing intersection of LM with IS at the point where the latter crosses ZZ . Monetary policy is impotent under fixed exchange rates.

A fiscal expansion under fixed exchange rates will shift the IS curve to the right, subject to the usual qualifications. The resulting rise in income to Y1 will increase the quantity of money demanded, causing domestic residents to sell assets to foreigners in return for money and creating a balance of payments surplus. To keep the domestic currency from appreciating, the central bank will be forced to accumulate foreign exchange reserves in return for domestic currency, putting additional money in circulation. This will shift LM to the right until it crosses IS at the intersection of IS' with ZZ. Fiscal policy is has its expected effect under fixed exchange rates.

In the long run, the excess of output above its normal level will cause wages and prices to rise. Given the fixed nominal exchange rate, this will raise the real exchange rate and make the small country's goods more expensive to both countries' residents, reducing the trade balance and shifting the IS curve back to its old level. The central bank will be forced, through changes in its foreign exchange reserve holdings, to adjust the money supply accordingly so that LM will also return to its initial level. Fiscal policy can thus be effective in changing the domestic price level and the real exchange rate under fixed exchange rates.

Another device for changing output and employment under fixed exchange rates is a devaluation of the nominal exchange rate to a new fixed level. At the initial levels of wages and prices this will reduce the real exchange rate in the same proportion and increase exports relative to imports, shifting IS to the right. The domestic authorities will then be forced to accumulate sufficient foreign exchange reserves to increase the supply of money to match the increased demand for it as output rises, shifting LM to the right by the same amount as IS. In the long run when wages and prices rise, the IS curve and real exchange rate will return to their original levels, leaving the domestic price level higher than it originally was in the same proportion as the devaluation of the nominal exchange rate. Notice that a devaluation will not affect the real exchange rate in the long run while properly implemented fiscal expansion will raise it. Tariffs, export subsidies and other expansionary commercial policies operate in exactly the same way as does a devaluation of the exchange rate.

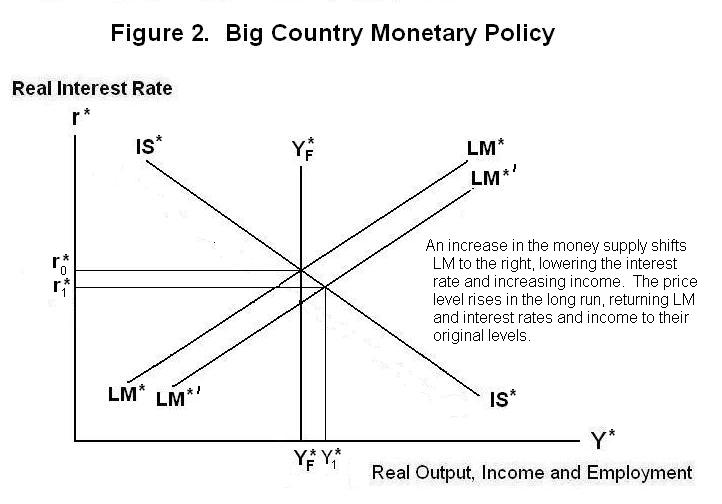

We now turn to the effects of economic policy in the big country on that country's employment, income and prices. By construction, the big country's trade balance is a tiny fraction of its income, so movements in the real and nominal exchange rates are of no consequence to big-country equilibrium. An increase in the money supply in the big country will shift its LM curve to the right, say to LM*′, in Figure 2. Big-country residents will attempt to purchase non-monetary assets with their excess money holdings, driving the domestic (and world) real interest rate down. Equilibrium will be re-established at the real interest rate r1* and the income level Y1* .

In the long run, the excess of employment over its natural or full-employment level will cause wages and prices to rise. This will reduce the real money stock, shifting the LM curve back to its original position. At that point income will have returned to YF* and the world interest rate to r0*. The price level will ultimately rise in proportion to the increase in the nominal money supply so that the real money supply returns to its initial level.

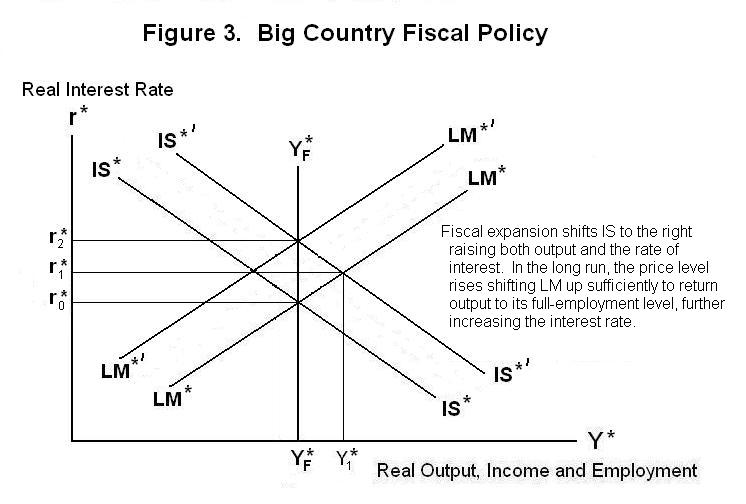

The effects of a fiscal expansion in the big country, subject to the qualifications noted in the earlier lesson dealing with fiscal policy, are shown in Figure 3. The IS curve shifts to the right to IS*′ causing the interest rate to rise to r1* and income to Y1* . In the long run, wages and prices rise, reducing the real stock of money and shifting LM to the left. Long-run equilibrium will be re-established at interest rate r2* where LM*′ crosses IS*′. Fiscal policy is thus effective in manipulating the world real interest rate and the domestic price level in the long run. This contrasts with monetary policy, which will affect nominal prices in the long run but leave the real interest rate and all other real magnitudes unchanged.

World equilibrium is also affected by exogenous shocks to consumption and investment and to the demand for money. In the big country, shocks to consumption and investment shift the IS curve and have essentially the same effects as fiscal shocks. Shocks to the demand for money shift the LM curve, affecting income and employment in the short run but only the level of prices in the long run as the LM curve shifts back to its initial position.

Shifts of the IS curve in the small country as a result of exogenous shocks to consumption and investment result in changes in income in the short-run and prices in the long run under fixed exchange rates. The real exchange rate changes in the same direction and proportion as the change in the price level. Shifts in the demand for money lead to identical changes in the supply of money as the central bank adjusts the stock of official foreign exchange reserves to keep the nominal exchange rate at its fixed level. This can be seen with reference to Figure 1.

Under a flexible exchange rate, consumption and investment shocks lead to real and nominal exchange rate adjustments which prevent the IS curve from moving away from the intersection of LM and ZZ in Figure 1. Monetary shocks will shift the LM curve and thereby affect income and employment in the short run. In the long run, wages and prices will respond, driving LM back to its original position. The nominal exchange rate will adjust to maintain the real exchange rate at its initial position. As in the big country, a nominal money shock only affects nominal magnitudes in the long run.

It's time for a test. Be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.