Most of the macroeconomic analysis in these Lessons, and

most practical analysis, involves countries that are very small

in relation to the rest of the world. Even a large country like

the United States will produce a relatively small fraction of the

world's output. The essential feature of small-country analysis

is that the country is too small to have any significant effect

on world saving, world investment, or the world interest rate.

World wide shocks impact on the small country but nothing that

happens in the small country has any significant effect on the

rest of the world.

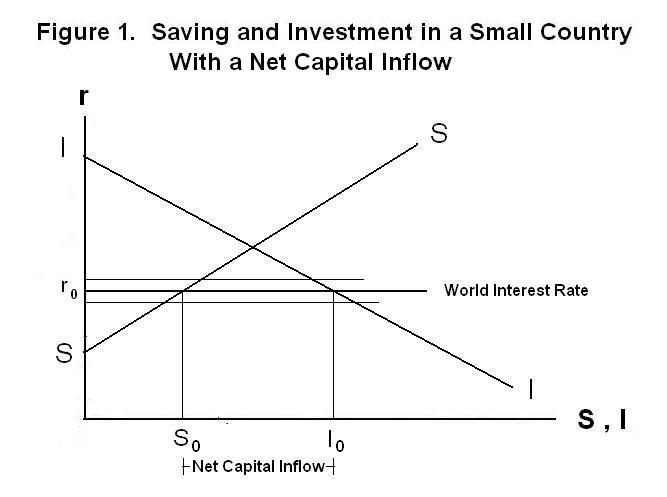

Suppose that a small country has the investment and savings functions I I and SS in Figure 1. Both these functions will reflect the institutional conditions in the small country and will typically differ from country to country. The world interest rate, r0, is determined in the rest of the world and independent of investment and saving in the small country. In the example shown in Figure 1, the country's investment exceeds its savings with the result that it is a net importer of capital---that is, is experiencing a net capital inflow.

It can easily be seen in Figure 1 that a rise in the world interest rate will cause the country's investment to decline and its savings to increase, reducing its net import of capital. And a fall in the world interest rate will increase investment, reduce savings and increase the net capital inflow.

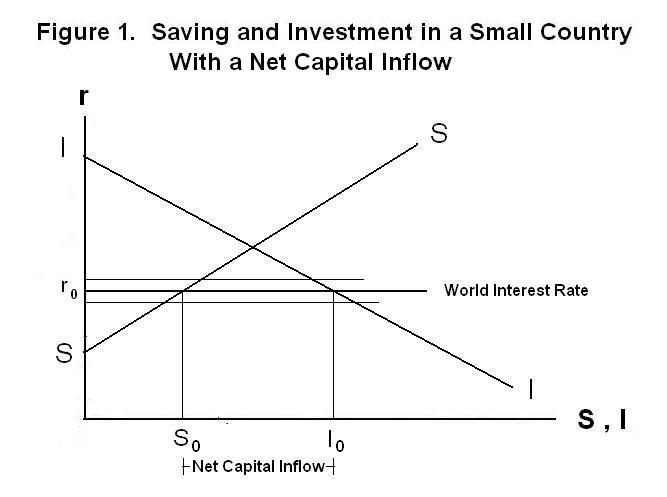

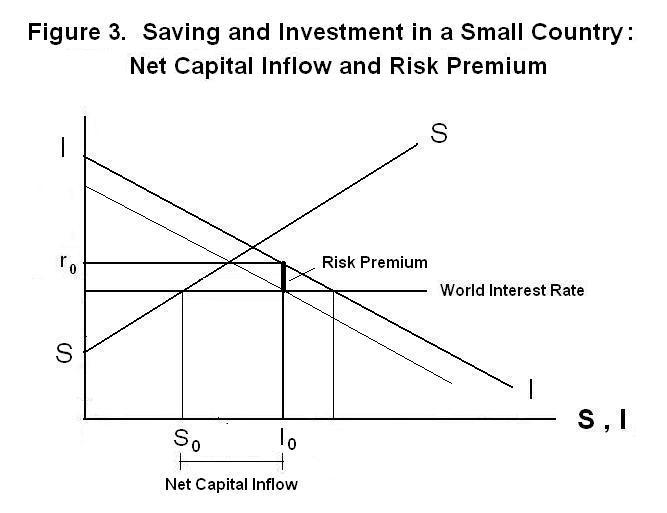

A different situation is shown in Figure 2. In this case the country's savings exceed world asset holders' investment in it at the existing world interest rate r0 so that there is an equilibrium net capital outflow. A fall in the world interest rate will increase investment and reduce savings and thereby reduce the net capital outflow. A rise in the world interest rate will increase savings and reduce investment, increasing the net capital outflow.

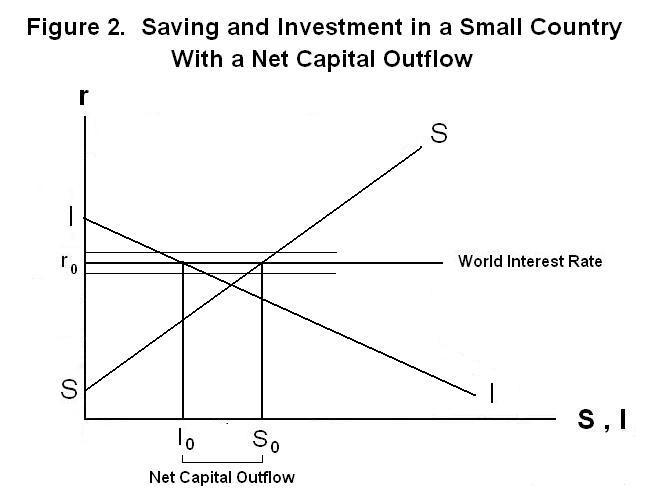

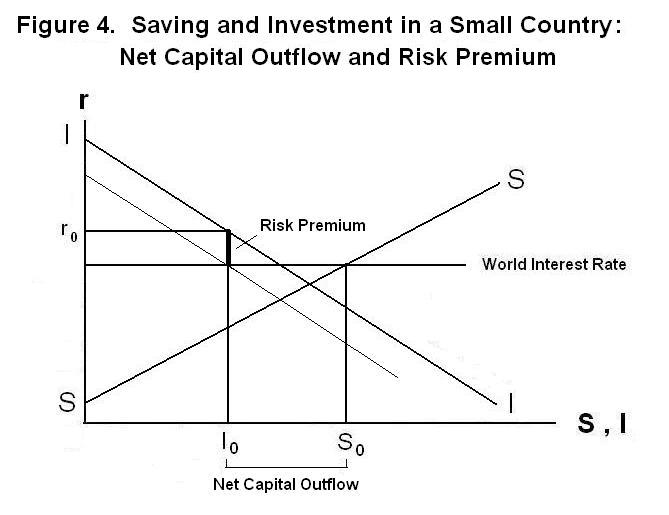

We have been letting the small country's interest rate be the same as the world interest rate. This assumes that the risk of investing in the small country is the same as the risk of investing in the rest of the world. Figure 3 and Figure 4 allow for a situation where the small country's economy is a more risky place to invest than the rest-of-world economy. In both cases there is a risk premium which reduces investment. The net capital inflow declines in Figure 3 and the net capital outflow increases in Figure 4. In both situations the domestic interest rate will exceed the world interest rate by a risk premium.

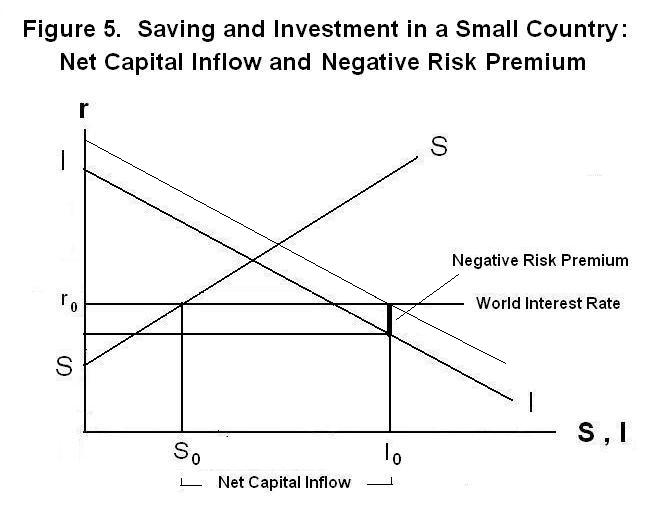

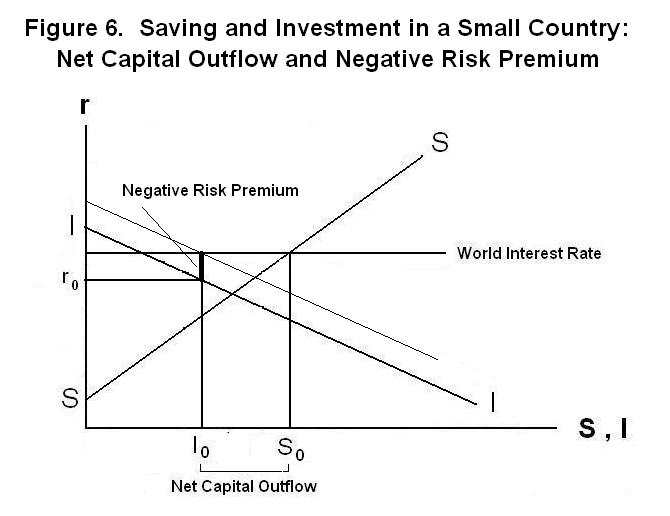

There is, of course, no reason why the risk premium need be positive. The small country might be a less risky place to invest than the rest of the world. This situation is shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6. The negative risk premium increases investment, increasing the net capital inflow in Figure 5 and reducing the net capital outflow in Figure 6.

The previous four figures also show the effects of shifts in world investment toward or away from the small country. A shift of investment toward the country may result from a perceived decline in the riskiness of investing in that country or may be a result of on-going changes in world technology that favour the particular natural resources with which the country is endowed. Correspondingly, a shift of world investment away from the country may result from an increase in perceived risk or from an endowment of resources less favorable to new world technology. In every case, shocks to the level of investment in the small country are completely absorbed by changes in the net inflow or outflow of capital, with no effect on domestic saving. In the cases where changes in risk are involved a positive or negative risk premium will emerge.

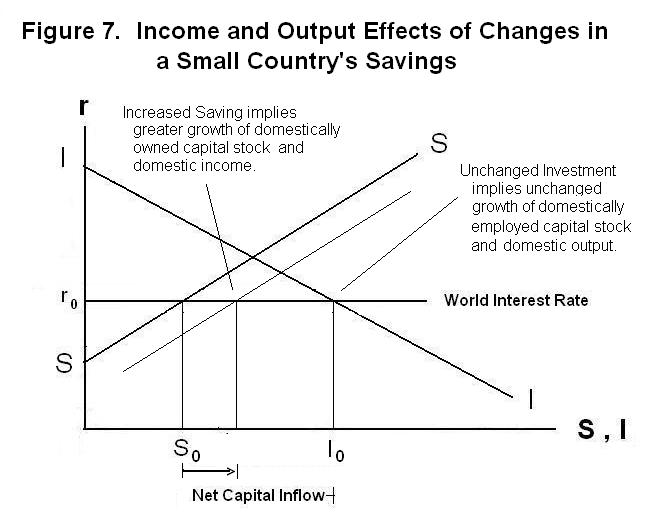

It is a straightforward extension of the above analysis to show that changes in savings in the small country will have no effect on that country's investment or output growth (although savings changes will affect the growth of the domestic residents' wealth). This is shown in Figure 7. In the case examined, an increase in savings reduces the net capital inflow.

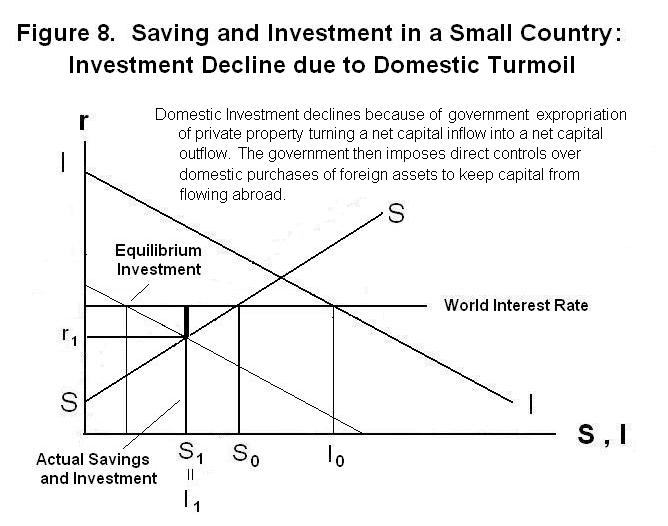

Shocks to savings need not always be based on a change in the residents' desired intertemporal allocation of consumption. One can imagine a situation where there is an implicit tax on saving of domestic residents reflecting the government's failure to provide secure property rights. Almost always, however, this sort of institutional breakdown will affect domestic investment even more than domestic saving. History is replete with examples of situations where investment in the domestic economy declines as a result of domestic turmoil or failure to enforce property rights and the government institutes controls over the purchase of foreign assets by domestic residents to prevent domestic savings from being invested abroad instead of in the domestic economy. This type of situation is illustrated in Figure 8. The investment function shifts to the left because, for example, a new government comes to power and adopts policies that will expropriate private property. An equilibrium net capital inflow turns into an equilibrium net capital outflow. The government then uses direct controls over the purchase of foreign assets to prevent domestic savings from going abroad. The actual net capital outflow is restricted at zero. This is equivalent to a tax on domestic savings equal to the difference between the rate of interest received by domestic residents, r1, and the world real interest rate.

It is time for a test. As always, think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson