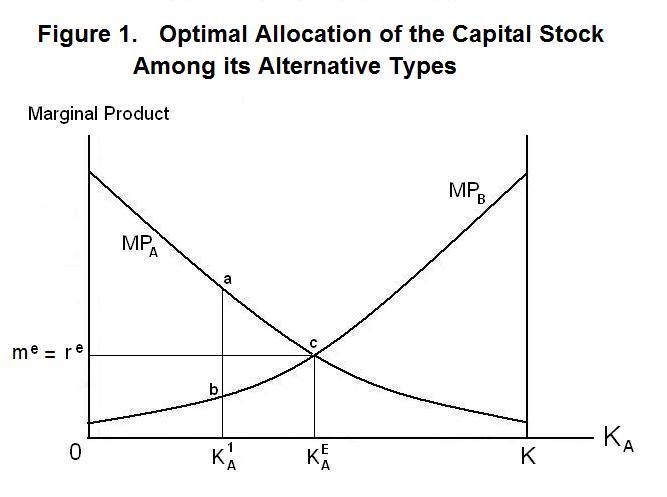

Our perfect efficiency assumption implies that the real rate

of interest, and the common marginal productivity of capital,

is me = re in

Figure 1, which is essentially a reproduction of Figure 1 of the

previous topic. The first question we must ask is how that rate of

interest will change when the stock of capital increases through

time as a result of saving and investment. It is possible that one

or both of the marginal productivity curves could shift up or down

as the capital stock grows. This would cause the real interest rate

to change through time as economic growth takes place. Since

aggregate investment involves an expansion of the various types of

capital in the optimal proportions, however, it is not obvious that any

change in me should occur.

We now turn to an examination of the process of saving

and investment and its effects on the rate of interest and the

rate of growth of income. To begin the discussion, we assume

that the private and social marginal products of capital are the

same for each type of capital and that the aggregate stock of

capital is allocated among the individual types of capital so

that the marginal product of capital is the same everywhere.

This is the case where the economy is perfectly efficient and

output is maximized. We will relax this assumption when we

proceed to the next Topic in this Lesson.

Although the stock of raw natural resources does not grow in step with the stocks of reproducible physical and human capital, it is not unreasonable to assume that growth of the stocks of knowledge and technology is sufficient to avoid diminishing returns to the expansion of the aggregate stock of capital on this fixed natural resource base. For example, diminishing returns to the employment of increased quantities of human and physical capital on a given stock of land need not occur as long as people keep inventing new and better farming methods. We lose nothing in the analysis that follows by adopting the simplifying assumption that me and re do not change as the aggregate stock of capital increases through time.

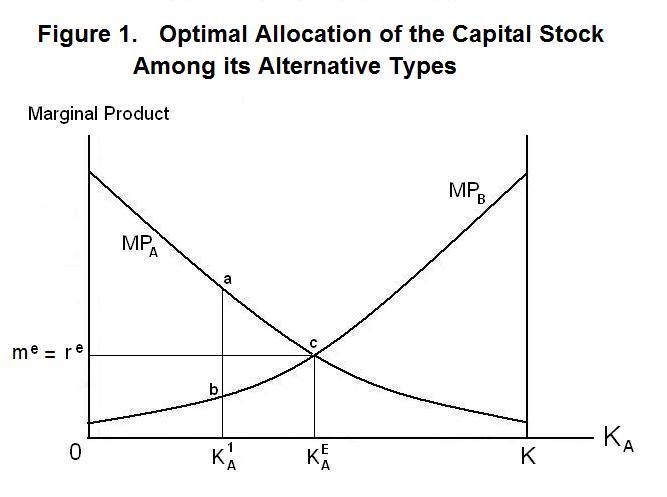

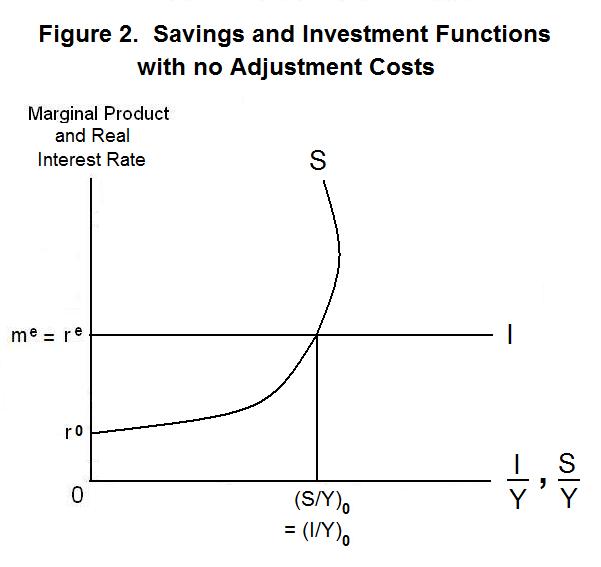

We have been defining a unit of capital as the quantity that can be obtained by sacrificing one unit of consumption. For the moment we will assume that new capital goods can be produced in any quantity desired at this one-for-one cost in terms of consumer goods. Together with our assumption that the marginal product of capital in the economy is independent of the level of the capital stock, this implies that the real rate of interest in the economy will be independent of the level of aggregate investment. The relationship between the level of investment and the level of the real interest rate is thus given by the line reI in Figure 2. The horizontal axis in the Figure gives the level of investment as a fraction of the level of output, which is identical to the level of income when we ignore depreciation.

The equilibrium level of investment will therefore be determined entirely by people's choices as to how much to save. And the level of saving will depend on, among other things, the real interest rate. Suppose that aggregate savings is zero at the real interest rate r0. Recall that the real interest rate measures the amount of additional future consumption every year in perpetuity that can be obtained by giving up one unit of consumption now. Saving is zero at r0 because people to not feel that the additional future consumption that can be obtained is worth the sacrifice. As the interest rate rises above r0 the incentive to save increases, making people willing to give up some current consumption for the now greater additional perpetual future consumption that can be obtained. At zero or low levels of saving, therefore, there is a positive relationship between saving and the real interest rate. This is shown by the r0S curve in Figure 2. A rise in the real rate of interest causes people to substitute future consumption, which is now relatively cheaper, for current consumption so saving increases. As the interest rate rises further and the level of saving increases, the rising interest rate has an additional effect. The higher interest rate means that the existing level of savings yields a higher level of future consumption so that the level of people's wealth increases at the current aggregate output level. Individuals are better off even if they do not increase savings. When wealth increases people usually want to buy more of everything, including both current and future consumption. Given that output is unchanged, an increase in current consumption will imply a reduction in the level of savings. Thus, the increase in wealth associated with the current level of income will, by itself, cause the ratio of savings to income to decline.

Therefore, some part of the increase in savings due to the substitution of future for present consumption on account of the fact that the rise in the interest rate makes future consumption more attractive relative to current consumption will be offset by an increase in consumption and decline in savings due to the effect of the increase in the interest rate on wealth. This wealth effect arises because the increase in the interest rate increases the amount of future consumption that will be obtained from the level of saving that existed before the interest rate rose. As a result of this wealth effect, saving increases by less and less in response to a rise in the interest rate as the ratio of savings to income increases. In fact, it is generally believed that at very high levels of savings a further increase in the real interest rate will cause the ratio of savings to output to decline ---this eventual domination of the wealth effect is shown by the backward bending portion of the r0S curve in Figure 2.

It is now a straight-forward exercise to determine the equilibrium growth rate of real output. Since the marginal product of capital is constant, independent of the capital stock, output will be proportional to the capital stock.

1. Y = me K

Given that savings represents growth of the capital stock,

2. ΔY = me ΔK = me I = me S .

where I and S are the levels of real investment and real saving. Output will increase by the amount

3. ΔY = me ΔK = me S

Divide both sides of Equation 3 by Y to obtain the growth rate of aggregate output

4. g = ΔY/Y = me S/Y

where me, it will be recalled, is the marginal product of capital when the stock of capital is efficiently allocated to its various uses and g is the growth rate of output. Output growth will be greater the higher the fraction of income that is saved.

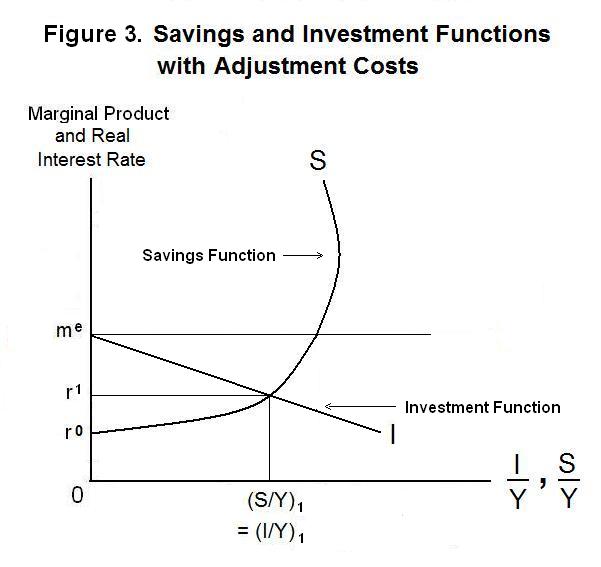

It is unreasonable, however, for us to assume that the real interest rate will be unaffected by the level of investment. It may be quite reasonable to assume that the economy can produce new units of each type of capital at a one-for-one cost in terms of consumer goods. It turns out, however, that there are two stages in adding a unit to the capital stock---producing that unit of capital, and blending it in with the existing stocks of the other types of capital. It may cost the same amount to actually produce a unit of capital whether investment is large or small. But it may be much more difficult to adjust existing capital to work with the newly produced capital when there are large additions to the capital stock than when only a small amount is added. Adding a large amount of may require a major reorganization of the way things are done in the production process. Introducing a new improved machine into a factory may involve simultaneous changes in the skills of the workers---the precise change in skills required as well as the efficient way to introduce those new skills may not be obvious until the new machine is added. These adjustment costs will tend to be larger the bigger the change in the aggregate capital stock---that is, the bigger the level of investment. It is thus reasonable to assume that the amount of consumption that will have to be foregone to put an additional unit of capital in place will increase progressively as the level of aggregate investment increases.

The additional perpetual future consumption yielded by a one-unit increase in the capital stock will equal

5. FC = meΔK = re

where ΔK = 1, while the amount of current consumption given up to obtain this increase in future consumption will equal

6. CC = 1 + α I/Y

where α is a parameter greater than zero. The actual rate of interest obtained will equal the perpetual future consumption that can be obtained by giving up one unit of current consumption, which will be

7. r = FC/CC = me / (1 + α I/Y) .

The rate of interest will be equal the marginal productivity of capital when investment is zero and fall below it by increasing amounts as the ratio of investment to income increases. This is shown in the downward sloping curve meI in Figure 3. This curve is called the investment function while the curve r0S can be called the savings function.

The equilibrium level of savings and investment relative to Y is determined by the intersection of the meI and r0S curves at r1. If r is above r1, savings will exceed investment---the quantity of new securities savers want to buy will be greater than the amount firms want to issue to finance current investment. The price of existing asset stocks will be bid up and the real interest rate will fall. Similarly, if r is below r1, there will be an excess supply of new assets and asset prices will be bid down and the real interest rate will be bid up.

Since the marginal product of capital is still me regardless of the size of the capital stock, output will continue to be proportional to the capital stock

Y = me K

as in Equation 1. It will still increase per year by

ΔY = me S

according to Equation 3. The growth rate of output will still be

g = ΔY/Y = me S/Y

as given by Equation 4, although it will be lower when we allow for adjustment costs because the level of saving and investment will be lower.

It is time again for a test. As always, think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson