1.

Y = F ( K1, K2,

K3,......, Kn )

where Y is aggregate income and K i is

the quantity of the i th type of capital where

i = 1, 2, 3, 4,... n.

The principle of diminishing returns implies that an increase the stock of

one type of capital relative to others will cause the marginal

product of that type of capital to fall and the marginal products

of the other types of capital to rise. We have seen that to maximize the

aggregate output obtainable from any given aggregate

capital stock the mix of the various types of capital must be such

that the marginal products of all types of capital are the same.

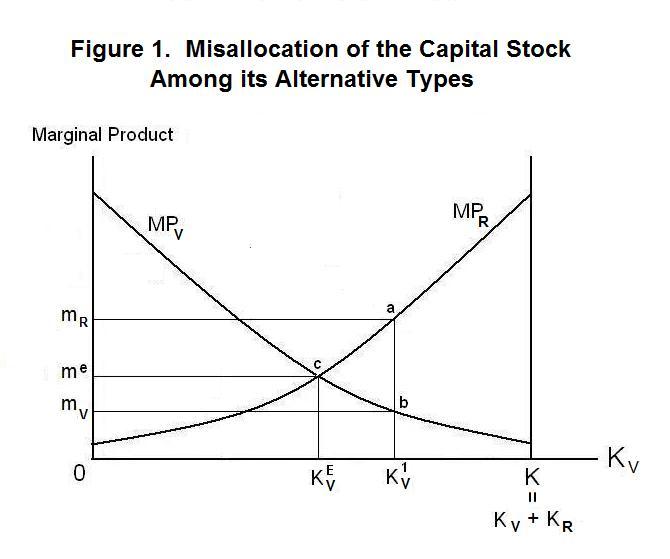

This is shown in Figure 1, which simplifies things by assuming only

two types of capital, KV and KR.

The efficient mix of the two types of capital occurs

at point c .

As we noted earlier, the most important cause of inefficiency

in the growth process is the inability of inventors of new knowledge

and technology to capture the social returns to their efforts. When

a new idea appears everyone in the economy can use it for free

unless its inventor can somehow obtain a copyright or patent on it.

While these legal means of maintaining ownership of new technology

are of value for many inventions, the use of many other technological

improvements cannot be effectively restricted because they are difficult

to define in legal terms or, once used, are so obvious that the

costs of restricting their use would be prohibitive. Because of these

difficulties, inventors have no incentive to produce certain types of knowledge

and technology.

Products that everyone in the economy can use simultaneously

are called public goods. The use of a private capital good,

like a car or a pair of shoes, is under the control of a single defined

owner whereas the use of a public capital good, like the concept

of the wheel, can be used by everyone simultaneously. It is thus

hard for producers of public goods to collect fees for their use

since any purchaser can resell the good to others without limiting

her own use of it. The lack of an incentive to produce many types

of knowledge capital means that their quantity will not grow optimally as

the economy's aggregate capital stock increases.

Our assumption in the previous Topic that the aggregate stock

of capital is efficiently allocated among all types of capital is

obviously unrealistic. Our purpose in this Topic is to relax that

assumption. To begin, we return to the production function that

was introduced in the first Topic of this Lesson. It expresses

income (which equals output when we assume no depreciation) as a

function of (i.e., determined by) the stocks of the various types

of capital:

We denote the capital that cannot be expanded optimally by KR in Figure 1. The unrestricted or freely variable forms of capital are denoted by KV. The optimal mix of the two types of capital is given at point c in Figure 1. When the restricted forms of capital cannot expand optimally as the total capital stock increases the equilibrium will move to a point such as b where the marginal product of the variable form of capital has fallen relative to the marginal product of the restricted form. Expansion of the variable capital forms increases output, but by not as much as it would increase if the restricted capital forms could also expand. The distance a b in Figure 1 shows the gain in output that could be obtained if the economy could have one more unit of KR and one less unit of KV.

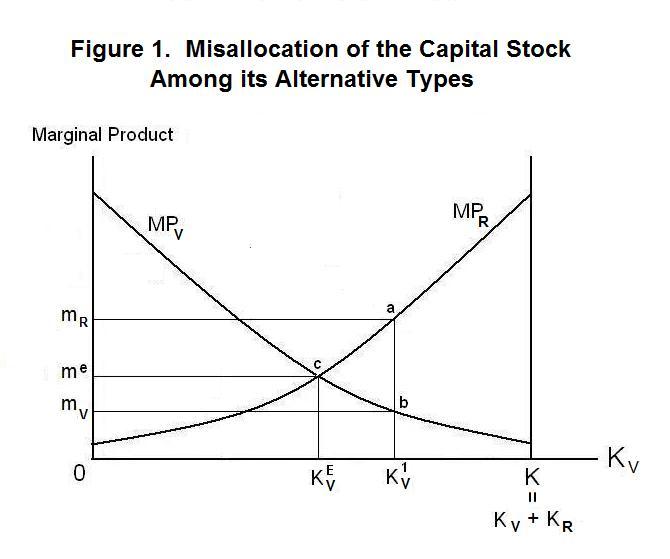

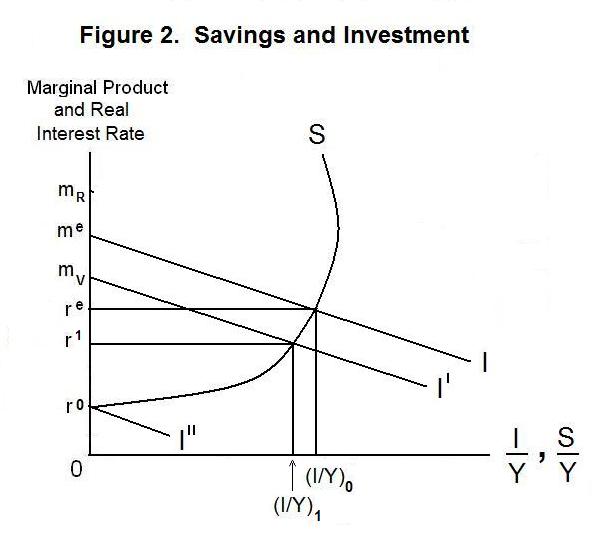

The effects on investment and growth of these restrictions on the expansion of certain types of capital is shown in Figure 2. The marginal product of capital in the economy under optimal conditions is given by me on the vertical axis. The investment function in the perfect efficiency case is me I and the equilibrium fraction of output saved and invested is (I/Y)0. When the stock of unrestricted capital expands through time relative to the stock of the restricted forms of capital the marginal product of the unrestricted capital gradually falls to mV and the investment function shifts down to, say, mV I′. At this point investment will have fallen to (I/Y)1 and the rate of interest in the economy will have fallen to r1. Meanwhile, the marginal product of the restricted forms of capital will have risen to, say, mR.

If the restricted types of capital do not expand at all, the ratio of KV to KR will eventually increase to the point where the marginal product of variable capital has fallen to r0 and the investment function has shifted down to r0 I′′, at which point saving and investment (and economic growth) will cease.

It turns out, however, that some expansion of knowledge and technology, the restricted forms of capital, will inevitably occur without conscious investment. New ideas occur in the process of production quite inadvertently. This is known as learning by doing. Moreover, some expansion of technology will also occur because inventors can capture some, albeit small, part of the social returns to their inventions. As this expansion of the restricted forms of capital takes place, at given levels of investment in variable capital, the marginal product of the unrestricted capital types, and the investment function in Figure 2, will shift upward, causing the ratio of savings and investment to output to rise along with the equilibrium real interest rate. This will tend to offset the downward shift of the investment function consequent on the expansion of variable capital.

A steady state equilibrium rate of growth occurs when the growth rate becomes constant through time as the process of saving, investment and capital stock expansion takes place. We might expect an equilibrium of this sort to occur at an interest rate and investment-to-output level where the upward effect of the expansion of the restricted forms of capital on the investment function just offsets the downward effect of the expansion of the variable forms of capital. At this steady state equilibrium point, shown at r1 and (I/Y)1 in Figure 2, the capital stock and output will grow at a steady-state constant rate. The growth of aggregate output will then be given by

2. g = ΔY / Y = m* (S/Y)

where m* is the an average of the steady-state marginal products of all types of capital. And per-capital income growth will equal g minus the rate of population growth.

The extent of restriction of the growth of knowledge forms of capital will depend on the country's underlying institutions. Patent laws may be better enforced in some countries than others. Also, government restrictions on market activity may prevent capture of the returns to innovation. Every change in the economy benefits some people and hurts others---efficient changes are those from which the gainers gain more than the losers lose. If the losers from particular innovations, be they labour unions or politically powerful competitors, have the political power to impede their adoption, the ability of inventors to acquire the benefits from new knowledge and technology can be drastically reduced. As a result, the investment function will be further downward to the left than otherwise, leading to less savings and a lower growth rate. Indeed, every misallocation of capital among its alternative uses, whatever the nature, will reduce the income stream from the aggregate and hence savings and growth.

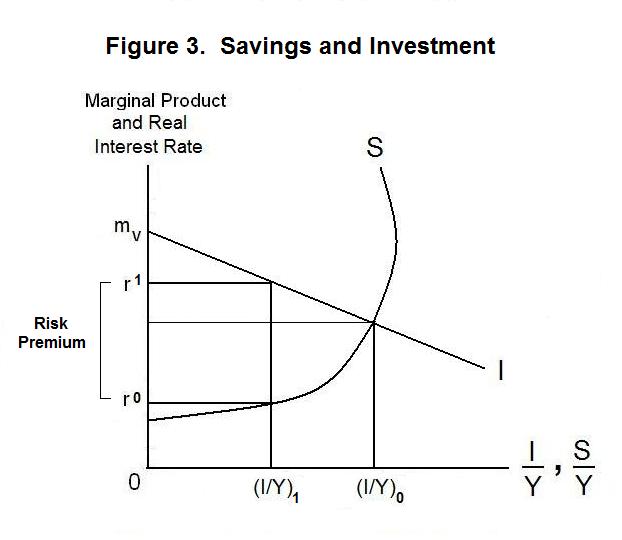

Things can be worse. In countries where property rights are not secure, capital stock can be destroyed or stolen. When the risk of this happening is high, the private returns to all capital, not just knowledge and technology, will be below the social return. A risk premium will be added to the interest rate, as shown in Figure 3. Saving will occur on the basis of the risk-free interest rate r0 while investment will be based on the risk-inclusive interest rate r1. The result will be a lower overall level of investment in all types of capital than otherwise and, again, a lower rate of income growth.

All of our analysis thus far is based on the situation of an individual country, isolated from trade with the rest of the world. Alternatively, it can be viewed as applying to the entire world, although it is then silent about the obvious differences in growth among the regions of that world. We next extend the analysis to a two-country or two-region framework.

But first, a test! As always, think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson