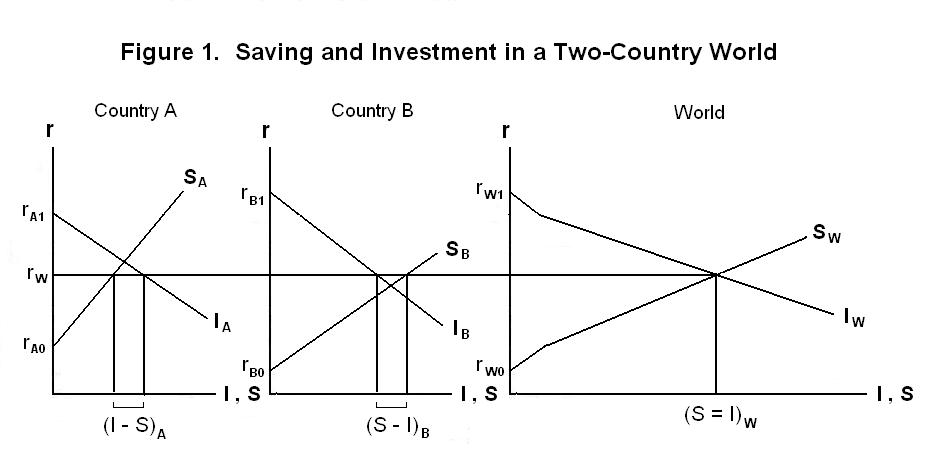

The savings, investment and growth process is analyzed with reference to

Figure 1. The two countries' investment functions are given

by rA1 IA

and rB1 IB. And their savings functions are

rA0 SA

and rB0 SB. The world investment and savings

functions are the horizontal summations of the respective savings and

investment functions of the two countries. Because the institutions in the

two countries differ, neither their investment functions nor their savings

functions cross the vertical axes at the same interest rate levels. And the

slopes of the respective functions also differ across countries.

The analysis thus far has assumed a single country that

is unconnected with the rest of the world or, alternatively, that

consists of the entire world. We now relax that assumption to focus

on a world of two countries, both of major size. The countries are

assumed to trade with each other and the residents of each country

can own capital employed in the other country. The institutional

structures in the two countries are assumed to be different so that

their growth processes are not equally efficient. Nevertheless, we

initially assume that the risks from holding capital are the same in

the two countries.

The world real interest rate is determined at rW by the intersection of the world savings and investment functions. Since we assume that the risk of holding assets is the same in both countries their domestic interest rates both equal the world interest rate. At that world interest rate there is an excess of investment over savings in country A and an equal excess of savings over investment in country B. One country's excess of savings over investment will necessarily equal the other country's excess of investment over savings because the world savings and investment functions are the horizontal sums of the respective functions in the two countries.

There is a net capital inflow into Country A because part of its investment is undertaken using savings from Country B. At the same time, there is a net capital outflow from Country B because a part of its domestic savings are flowing into investment in Country A. Capital---that is, accumulated savings---is thus flowing from B to A. We are using the word capital here to mean ownership claims to capital goods, not the capital goods themselves. When trade in both goods and assets is possible, assets owned by the residents of one country can be claims on capital goods employed in the other country. And some portion of the capital goods employed in each country will typically have been produced in the other country and imported.

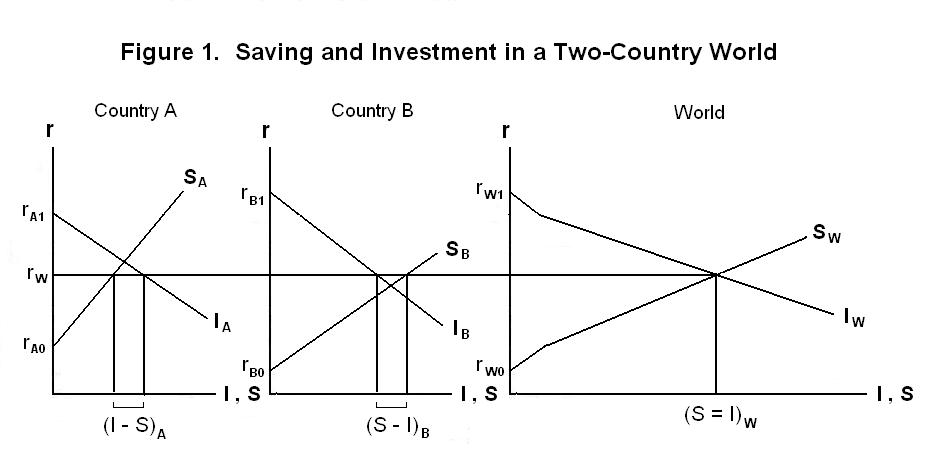

Now let us suppose that there is a technological shock in country A that raises its marginal product of capital. This could result from an institutional change or a random discovery within the existing institutional framework. Since investment decisions depend on the expected future rather than the current productivity of capital, the shock could also could result from a change in investors' expectations. The effect is shown by the thinner lines in Figure 2. The upward shift of Country A's investment function causes the world investment function to shift to the right. The world real interest rate interest rate rises. The world interest rate rises by much less than the upward shift of Country A's investment function since Country A's investment is less than half of world investment. Investment increases relative to savings in Country A and declines by an equal amount relative to savings in Country B. The net capital flow from B to A therefore increases. Thus, an actual or expected improvement of productivity in one country increases world investment and the world interest rate. World savings also rise, with capital flowing into the country in which the expected return to capital increased.

If the world is in a steady state growth equilibrium the growth of all types of capital will be in a balance that will hold the world real interest rate constant. Still, technological growth may differentially affect the returns to capital in the two countries. As growth occurs the new technology may use natural resources that are more plentiful in one of the countries. The investment function of that country, say Country A, will shift to the right and the investment function of the other country will shift to the left by an equal amount. There will be an equivalent increase in the net capital flow from Country B to Country A (or a decline in the net flow from A to B).

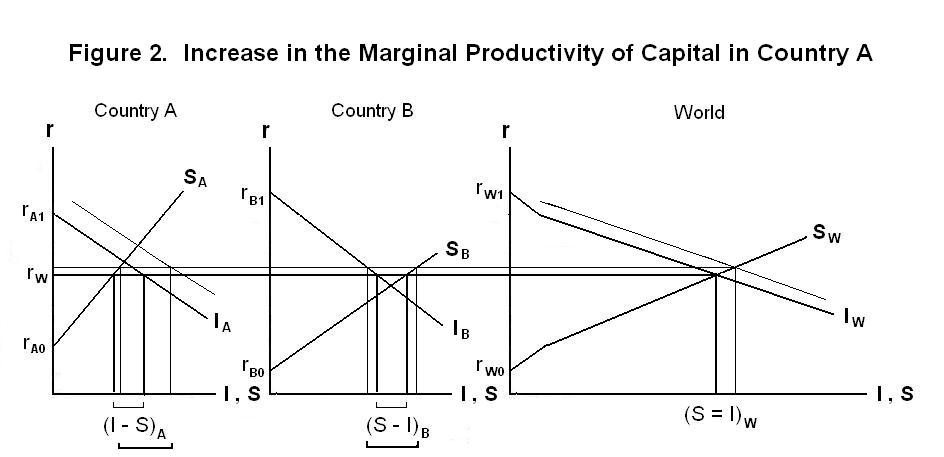

Now suppose that the residents of one of the countries, say Country B, decide to shift consumption from the present to the future by saving a greater fraction of their income. The curve rB0 SB will shift to the right in Figure 3, along with the world savings function. The world interest rate will fall and the level of investment will increase in both countries. Savings will increase relative to investment in Country B and decline relative to investment by an equal amount in Country A. The net capital flow from Country B to Country A will increase. An increase in desired saving in one country will thus lead to a reduction in the world interest rate, an increase in world investment and an increased net capital flow out of (or reduced net flow into) the country whose savings increased.

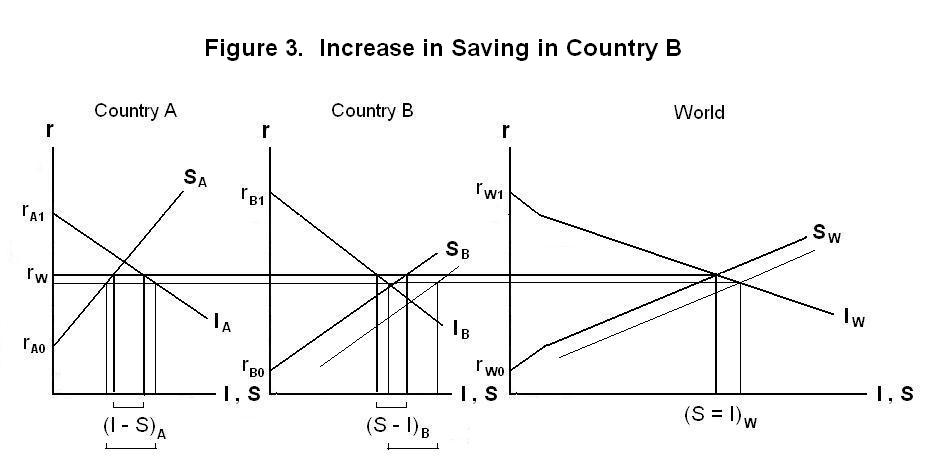

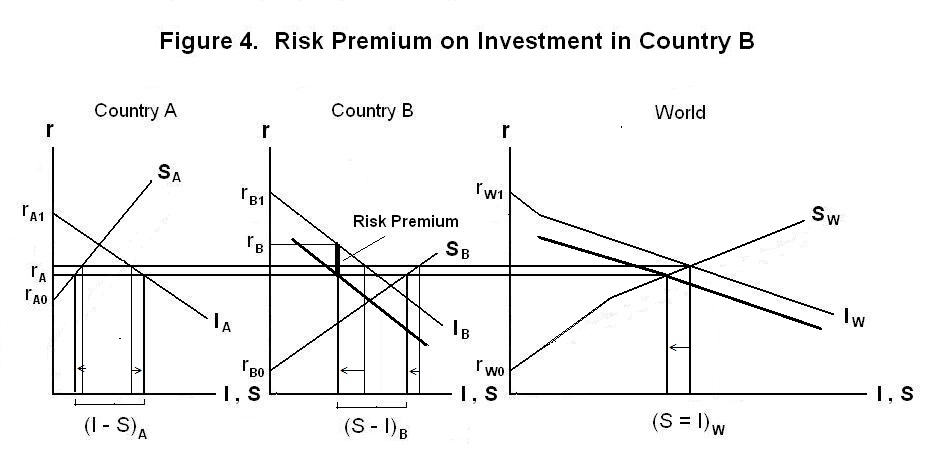

Finally, let us relax our assumption that the risk from holding assets is the same in the two countries. Suppose that government policy is less predictable in Country B than Country A. Or, alternatively, suppose that Country B, because of its natural resource base, is specialized in industries that are inherently more risky than others in the world economy. A risk premium will be required to induce world residents to invest in Country B. That country's risk-adjusted investment function is given, along with the risk-adjusted world investment function, by the thick lines in Figure 4. The world investment function is now the horizontal sum of the risk-comparable individual country investment functions and shifts to the left as a result of the imposition of risk. The savings functions in the two countries are defined at a risk-comparable interest rate so that the interest rate relevant for savings in Country B is Country A's interest rate. The interest rate in Country A is rA and the interest rate in Country B is rB, which differs from rA by the risk premium. Because of the imposition of risk, less investment is undertaken in country B, and hence in the world as a whole, so there is a slight fall in the world interest rate. This causes savings in both countries to fall. Investment falls in country B and shifts to a considerable degree to country A, whose investment also increases as a result of the fact that the world interest rate is now lower.

Changes in the risks of investing in the two countries are a further factor leading to changes in world interest rates and net capital flows. The response of interest rates and net capital flows to changes in risk is identical to the response to all other shocks to the individual countries' investment functions. The analysis is the same except that it must now be kept in mind that the world savings and investment functions are the horizontal summations of risk-comparable functions in the individual countries.

It is test time. Be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson