Imagine a portfolio containing with every marketable non-fixed-income

asset in the economy with the share of each asset in the portfolio

being the same as the share of that asset in the total---call this

the market portfolio. That portfolio will have a return that will

not be constant because factors affecting economic activity in general

will impact on many different stocks. Indeed, the prices of the assets

in the portfolio will be bid up or down until the resulting returns

reflect the risks of holding those individual assets.

The riskiness of an asset does not depend on the variability of the

return on it. Rather, it depends on that part of its variability

that cannot be diversified away by pooling it with other stocks in a

diversified portfolio. There are two types of risk involved here.

First, there is diversifiable or idiosyncratic risk that is reflected in

the variability of each stock independent of the others. This risk

can be eliminated by collecting together a large enough pool of

stocks, appropriately weighted in constructing the portfolio, so

that the average idiosyncratic shock is virtually zero. The second type of

risk is non-diversifiable or systematic risk which is represented by

variability common to all assets in the broadest possible portfolio.

This type of risk cannot be eliminated by diversifying the portfolio.

The risk of the above-defined market portfolio---which obviously cannot be

diversified away---can be thought of as a basis for comparing asset returns.

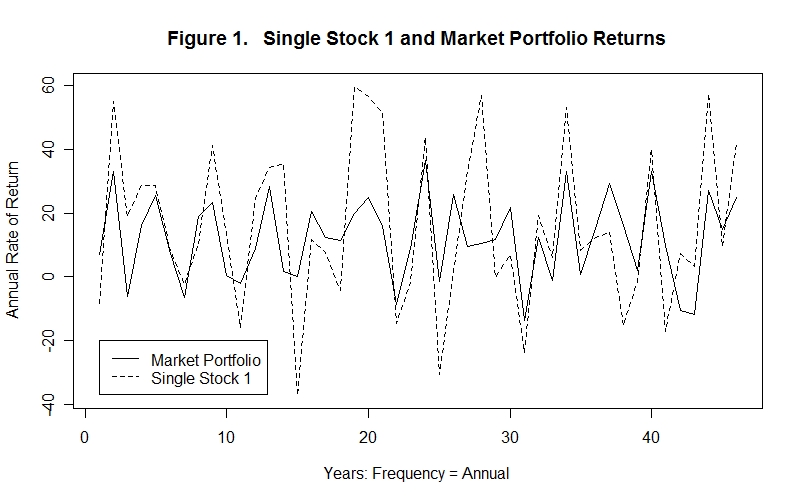

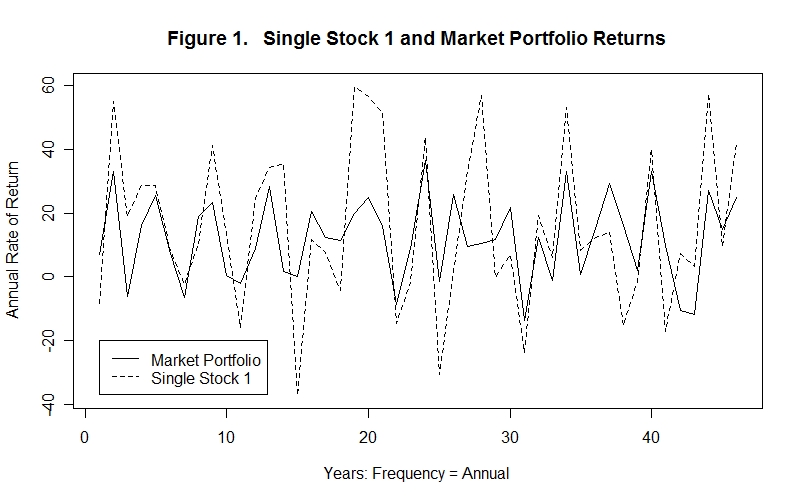

An asset whose return is correlated with and varies much more than the return

to the market portfolio makes, by its presence, the variability of the return

to the market portfolio higher than it would otherwise be. It is therefore

more risky than the market portfolio and asset holders will bid its price

down sufficiently to make its return appropriately higher than the return to

the market portfolio to compensate for this additional risk. An example of

such an asset is illustrated in Figure 1.

The Toronto Stock Exchange TSX300 Index represents about as

diversified a portfolio as one could imagine, yet the return

still shows considerable variability. Since the weights of the

stocks in the TSX300 portfolio do not take into account the facts

that the returns to some stocks are more variable than the returns

to others and that the returns to the various stocks tend to be

positively correlated with each other, it would be possible to

find a subset of stocks in the portfolio which will have a less

variable return than the return to the whole portfolio. And it

would be possible to find another group of stocks whose average

return would be more variable than the return to the whole portfolio.

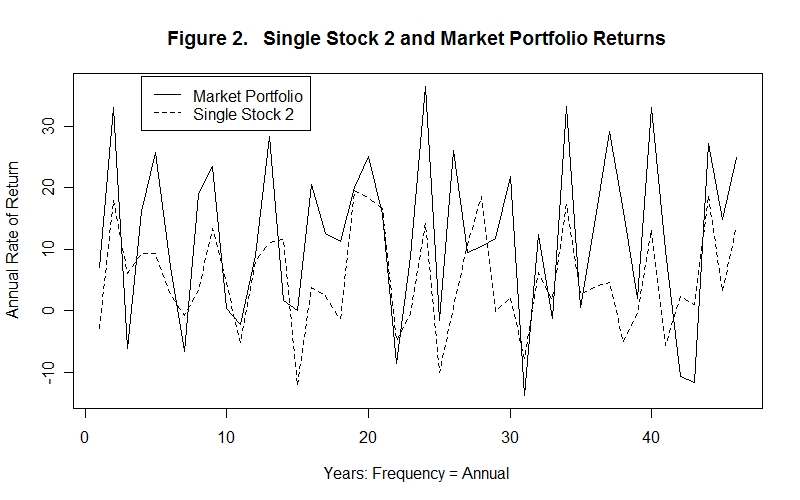

Now consider an asset whose return is less variable than the return to the market portfolio. Including it in the market portfolio reduces the variability of the return to that portfolio compared to what it otherwise would be. It therefore has lower non-diversifiable risk than the market portfolio and asset holders will therefore bid its price up sufficiently to make its return appropriately lower than the return to the market portfolio to compensate for the lower risk. An example is illustriated in Figure 2.

Those stocks that show greater amplitude of variation in upswings and downswings than the average stock in the market contribute greater variability to any portfolio that contains them. So the earning streams from such stocks are less valuable than equivalent earning streams from stocks that show the same amplitude of fluctuation as the market. At the same time, stocks whose returns vary very little in proportion to the market returns as they rise and fall tend to reduce the variability of any portfolio they are in and, as a result, the earnings streams from these stocks are valued more highly than the income streams from stocks that show the same amplitude of fluctuations as the market as a whole. The former stocks are high risk stocks and the latter are low risk stocks.

A useful measure of the risk from holding a particular stock is the covariance of the return to that stock with a broad market portfolio divided by the variance of the market portfolio. The variance of a series of returns was defined in the previous topic---it is the sum of the squared deviations of the individual periods' returns from the mean return, divided by the number of periods.

Letting X be the series of market portfolio returns, this is

var(X) = [(X1 - mean(X))2 + (X2 - mean(X))2 + (X3 - mean(X))2 + (X4 - mean(X))2 + ................... + (XN - mean(X))2] / N

The covariance of the return to a particular series, denoted by Y, with respect to the return to the market portfolio is defined as

cov(Y,X) = [(Y1 - mean(Y))(X1 - mean(X)) + (Y2 - mean(Y))(X2 - mean(X)) + (Y3 - mean(Y))(X3 - mean(X)) + ......................... + (YN - mean(Y))(XN - mean(X))] / N

The covariance is thus the sum of the products of the deviations of each period's two returns from their respective means, divided by the number of periods.

The risk of the individual stock in question relative to the market portfolio, commonly called its beta coefficient, is measured as

beta(y,x) = cov(Y,X) / var(X)

Students in first-year statistics courses should recognize that the beta coefficient is simply the slope coefficient of an ordinary least squares regression of Y on X. Of course, beta coefficients can be calculated for individual stocks with respect to any portfolio of stocks one might construct. Indeed, the basic underlying problem in any situation is how to determine what to use as the market portfolio. The beta coefficients for the stocks in Figures 1 and 2 are, respectively, 1.2 and 0.4.

One can easily earn a greater return than earned in the market as a whole without having better information than other investors have. One simply invests in a portfolio of stocks that have greater non-diversifiable risk---that is higher beta coefficients. The price one pays for doing better on average over the long-haul is the greater beating one takes when the market declines. The riskier portfolio does better than the market on average, even better than the market on the upswings, and worse than the market on the downswings. One can also easily reduce one's risk by investing in stocks with beta coefficients that are much lower than unity---the price that will be paid is the resulting reduction in one's portfolio return.

We conclude from this that, despite the gains from diversification, asset owners who have no more information than the rest of the market face a tradeoff between risk and return. To earn a higher return, on average, one must bear greater risk---to reduce one's risk, one must be satisfied with a lower return on average.

Diversification and risk management are important not just for stock market investing. Asset holders diversify over a very broad range of assets including bonds and real property as well as equity shares. Sometimes bonds do well when stocks do poorly and vice versa. Real estate values typically do not follow the same pattern as either stocks or bonds and the risk from property holdings can be reduced by diversifying across different locations. Human capital is the most difficult asset holding to diversify in that most people can acquire only a limited range of expertise.

We noted during the Lesson entitled Interest Rates and Asset Values that a risk of holding bonds is the possibility that the price level will rise unexpectedly, reducing the real value of the principal and interest by an amount not compensated for in the inflation premium incorporated in the nominal interest rate. Because investors' expectations of future inflation and future real interest rates can change, bond prices may fluctuate substantially.

Another of risk from holding bonds is the risk of default. The issuer of the bond guarantees to pay back the principal with interest regardless of what happens to his own financial state. Occasions arise where issuers, because of adverse circumstances, default on these payments. The greater the likelihood of default, the higher the interest rate investors will require to get them to purchase and hold the bonds. A perceived increase in the likelihood of default will cause the present value of the future earnings from the bond, and hence its market price, to decline, and the yield (capitalization rate) on the bond to rise.

Information about the default risk from holding various bond issues is valuable to investors, so it is not surprising that a number of agencies have arisen to collect and disseminate such information. Three agencies of this sort in the United States are Moody's Investor Service, Standard and Poor's Corporation and Fitch Investor Service. A comparable agency in Canada is the Dominion Bond Rating Service. These firms assign bonds into A and B risk categories. A lower rated category of bonds, called junk bonds, which are not permissible investments for institutional investors such as pension funds and insurance companies, also exists. These ratings give an investor a rough idea of the default risk being borne.

It is now time for a test. Be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson