The aggregate income of residents of the small economy will

depend upon how much capital stock they own and on the marginal

productivity of that capital. Since the allocation of capital

among its various component types and across industries and

countries is always far from perfect, the marginal products of

capital will differ across capital types and uses. We will

assume that the world economy is on a steady-state growth path

along which these marginal products, though different, are

constant.

We can think of domestic residents as earning an income

composed of the sum of the of the quantities of the various types

of capital they own multiplied by the respective marginal products:

1.

Y = mDR KDR

+ mDV KDV +

mFR KFR + mFV KFV

where the m-terms are the marginal products and the K-terms are

the quantities of capital owned, with the D and F subscripts

referring to whether the capital is employed in the domestic or

foreign economy and the R and V subscripts referring to whether

the capital is of a type whose growth is restricted by non-capturability

of returns to investment and other institutional restrictions or freely

variable in response to its social return.

Note that the marginal products in the equation above are

the social, not the private, marginal products because all the

output flow from the capital accrues to someone in the society,

though not necessarily to the actual individual who made the

investment to produce that capital or who technically owns it.

We can think of any person to whom returns from a particular

piece of capital accrue as in fact owning some corresponding

portion of that capital, even though some other person may hold

the title to it.

Under conditions of perfect efficiency, of course, investment

will be allocated so as to drive the marginal products into equality,

at which point domestic and world measured real income will

be maximized. Given that level of measured real income, aggregate

domestic wealth will be highest if people are able to allocate that

income to the purchase of the various goods and services in the

most efficient manner.

Given the domestic interest rate, which for reasons shown

earlier in this Lesson will almost certainly be below the marginal

products of all types of capital, domestic residents will save an

equilibrium and, we assume, constant fraction of their income. As

a result domestic income will grow at the rate

1.

ΔY / Y = m* ΔK / Y =

m* S / Y

where m* is an average of the marginal products of the various

types of capital owned by domestic residents and S / Y is the

fraction of income saved. Policies that can improve efficiency and

increase m* will increase the growth rate.

The growth rate can also be increased by increasing S / Y.

We must keep in mind, however, that the fraction of income saved

depends on domestic residents' choices and hence partly on their

preferences. Forcing people to save more will not necessarily

make them better off and therefore may not increase domestic

wealth. This will be seen clearly in the context of the analysis

of population growth to which we now turn.

Per capita income and wealth depend not only on the level

of aggregate income but on the size of the population that must

share that income. Population growth reflects the number of

children raised per adult, which depends on people's choices as

to family size. In a modern society in which people have substantial

human capital embodied in them, a decision to raise more

children implies a simultaneous decision to either consume less

in one's lifetime or embody less human capital in those children.

The embodiment of human capital in one's children is in large

part a process of parental investment. The resources required to

make this investment must come from reduced parental consumption

or a reduction in family size.

Nevertheless, not all human capital growth requires conscious

investment. Much is learned from simply observing the behaviour

of one's parents and others in society. In primitive societies in

which work tasks are relatively simple, this automatic accumulation

of human capital may be sufficient for children to achieve the same

knowledge and skill levels as their parents. As a result, the

opportunity cost of increasing family size may be small. Moreover,

children may be able to work and produce more than their subsistence

at an early age, so that having a larger family may enable parents

to increase their consumption.

We will restrict our analysis to advanced societies and

concentrate on the case where conscious positive investment in

children is necessary to give them the same human capital as

their parents. Parents thus have to forego their own consumption

to enable their children, upon adulthood, to have the same per

capita income as themselves. Our focus is thus on a three-dimensional

choice which all adults must make---how much to consume, how much to

save, and how many children to raise.

The saving dimension of this three-dimensional choice problem represents

intergenerational saving rather than saving for retirement---the issue is

how much capital, in either human or non-human form, is passed on to the

next generation and not on how people allocate consumption over their

lifetimes. People choose to consume a given amount themselves over their

lifetimes and devote the remainder of their lifetime income to investment

for the benefit of the generation to follow. Simultaneously, they choose

the size of the next generation that will share that inherited capital.

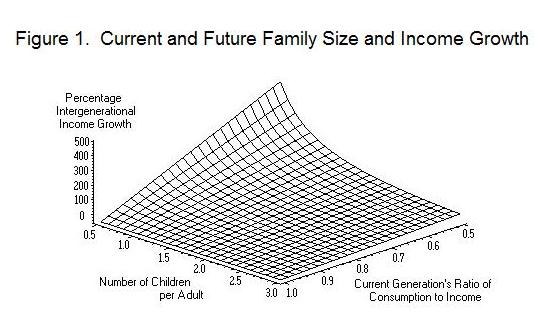

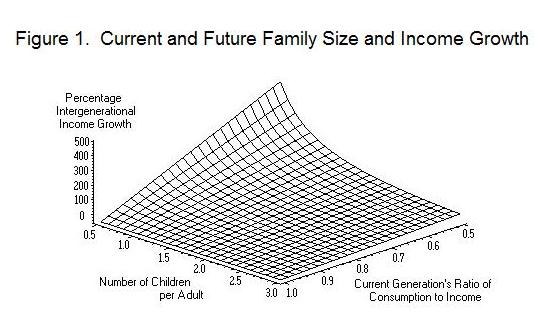

The current generation's budget constraint is modelled in Figure 1. The

number of children raised per adult and the fraction

of lifetime income consumed by the current generation are on the

two bottom axes. The percentage growth of income per person from

the current generation to the next is shown on the vertical axis.

Zero percentage growth means that the next generation has the same

per capita income as the current generation. It is obvious that to consume

a greater fraction of its lifetime income, the current generation must

either reduce the number of children it raises or reduce the

investment in those children and the per capita income attained

by the next generation.

We end this Lesson with a consideration of the forces

determining per capita income growth. There are, of course, two

issues involved. First, what causes growth of income and how can

we, or should we, try to make it grow faster? Second, what causes

population growth and what, if anything, should be done to make it

grow slower so that per capita income growth can be increased?

We will begin by reviewing what we have learned about the

factors determining growth of aggregate income and then turn our

attention to the analysis of population growth. We will focus

our attention on the situation of a small economy operating in a

large world.

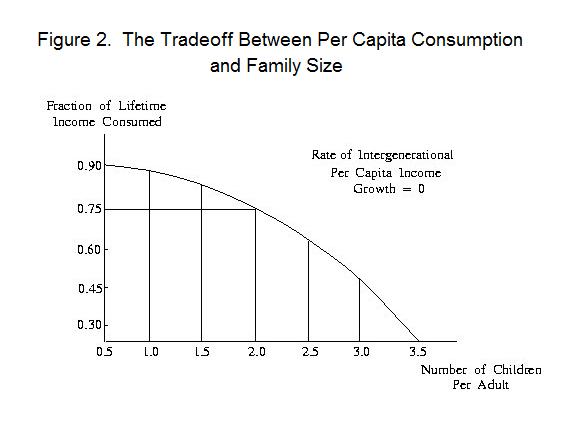

The tradeoff between fraction of income consumed and number of children raised per adult on condition that the next generation have the same per capita income as the current one is illustrated in Figure 2. If the current generation is willing to raise one-half child per adult (one child per pair of adults) to have the same standard of living as its parents, about 90 percent of lifetime income can be consumed. To increase family size to four children (two per adult) the fraction of income consumed will have to be reduced to 0.75 if the next generation is to have the same standard of living as the current one. To increase the standard of living of the next generation, either number of children or the fraction of lifetime income consumed must be reduced.

The current generation must choose some point on the opportunity surface in Figure 1. That point will determine the number of children raised per adult (and hence the rate of population growth), the fraction of current lifetime income consumed (and hence the intergenerational growth of aggregate income) and the percentage growth of per capital income from this generation to the next. Each member of the current generation will choose the point that maximizes his/her utility. This will determine the rates of growth of aggregate output and population, and hence income per capita, between the current generation and the next.

How can we increase the rate of growth of the per capita income of a country's residents? The obvious first step is to make the institutional changes necessary to achieve the most efficient allocation of investment among the various types and locations of capital so that output can be maximized. The entire opportunity surface in Figure 1 will shift outward. This will increase aggregate income growth because any given fraction of lifetime income saved will lead to greater growth of the capital stock and output for each number of children raised.

The key to maximizing the growth rate is to always channel investment to the projects having the highest social present value---that is, to where the future social returns discounted to the present at market interest rates is greatest. This will ensure that investment in knowledge and technology will be based on the true social return and not the fraction of that return capturable by private investors. The problem, of course, is that it is extremely difficult to calculate the social returns to many investments. And the allocation of capital among types and locations is heavily influenced by government restrictions that would require major institutional changes (modifications of institutional capital) to eliminate. Institutional changes work through the political system and cannot be easily forced upon a community.

Another obvious but even more difficult step is to increase the growth of a community's per capita income by forced savings and restrictions of population growth. The problem here is that the society's decisions as to how much to save and how many children to have are based on the free choice of its members. Should its government be advised to interfere with these private choices? If private choices are distorted by misinformation and government restrictions a good case can be made for removing these distortions. Beyond that, policies of forced saving and restrictions on family size involve philosophical issues that go beyond economics.

It's time for a test! Again, think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson