The central bank, acting on the government's behalf, can

move the real exchange rate by means of monetary policy under a

flexible exchange rate regime when there is less-than-full employment.

Fiscal and commercial policy can also permanently alter the real

exchange rate under full-employment conditions while monetary policy can

affect only the nominal exchange rate in this case. Fiscal and

commercial policy will affect the nominal exchange rate whenever it is

flexible.

It is also widely believed that the government can manipulate the nominal

exchange rate by simply buying and selling foreign currency for domestic

currency on the international market. This argument is analyzed below.

But first we need to investigate the ability of the small open economy's

authorities to manipulate domestic interest rates.

From the computer-assisted learning module The Foreign Exchange Market

you should have learned that the domestic and foreign nominal and

real interest rates are related as follows:

1. id

= if + Eπ + ρ

2. rd

= id - Epd

3. rf

= if - Epf

4. rd

= rf - Eq + ρ

where i and r are the nominal and real interest rates

respectively, the subscripts d and f denote domestic

and foreign, and Eπ , Eq and

Ep are, respectively, the expected rates of change of

the nominal and real exchange rates and price level.

The first equation says that the domestic nominal interest rate must exceed

the foreign nominal interest rate by an allowance for risk ρ

plus an amount equal to the capital loss expected on domestic

nominal assets relative to foreign assets from the future rise in

in the price of foreign currency in terms of domestic currency---otherwise

people would shift asset holdings between domestic-currency and

foreign-currency denominated bonds. The second and third equations are the

Fisher conditions---each country's nominal interest rate must equal its real

interest rate plus the expected rate of inflation. The fourth equation

says that the domestic real interest rate must exceed the foreign

real interest rate by the risk premium minus the expected rate of

increase in the real exchange rate---an increase in the expected real

exchange rate creates an expected capital gain from holding domestic rather

than foreign real capital goods, making it profitable to hold

them at a lower real interest rate.

Equation 4 implies that the domestic authorities can raise

the domestic real interest rate by making domestically held

capital more risky---that is, increasing ρ ---or by inducing

an expected future decline in the domestic real exchange rate. The latter

could be brought about by reducing the money supply under circumstances where

domestic residents know that the resulting appreciation of the real exchange

rate is a temporary overshooting adjustment that will subsequently dissipate.

If the exchange rate is perceived to be a random walk, however, the

expected future real exchange rate will always equal the

current rate and Eq will be zero. These conditions give

the small country's central bank little room to manipulate the

domestic real interest rate.

It is quite easy for the domestic central bank to manipulate

the nominal interest rate. By changing the rate of expansion of

the domestic money supply it can ultimately change the domestic

rate of inflation. As soon as the new rate of inflation

becomes anticipated the domestic nominal interest rate will

adjust accordingly. Although changes in the real interest rate,

if perceived to be permanent, are likely to affect domestic

investment, nominal interest rate changes by themselves have no

effects on investment, output and employment.

The above conclusions seem to conflict with the assertions

of most central banks that they conduct their monetary policy by

manipulating domestic interest rates. On closer examination of

these claims, however, it is apparent that the interest rates

central banks claim to control are the interest rates on overnight

loans of reserves between commercial banks and not the real

interest rates that enter into the determination of investment

expenditure. As banks clear cheques drawn on each other, reserves are

constantly shifting from bank to bank. Since these reserve

holdings bear minimal interest, banks will choose to keep them as

small as is consistent with their obligations to their depositors

and any government regulations that apply. When a bank's

reserves are drawn down unexpectedly it will borrow reserves on

an overnight basis from other banks who have a surplus over their

needs. When all banks find themselves short of reserves the

interest rate on these overnight borrowings will increase and

when they have surplus reserves the overnight rate will decline.

These interest rates on overnight borrowing will never

diverge persistently from the interest rates on the broad range

of other assets in the economy because, given a few days or a

week, banks can always liquidate their assets to replenish

reserves or shift excess reserves into a broad range of assets.

And the domestic interest rates at which banks can lend and borrow

in the economy as a whole are anchored to foreign interest

rates on securities of equivalent risk and maturity.

In many cases a central bank, by increasing and decreasing the reserves

of the banking system, can substantially move the overnight rate

on inter-bank loans, but the effect is necessary temporary

since the banks can access the broader capital market within a

day or two. Every time the central bank expands reserves, of

course, it increases the money supply and every time it contracts

reserves the domestic money supply declines. Central banks

usually also set an interest rate at which they will lend as a

"last resort" to commercial banks that are short of reserves.

This interest rate, called bank rate, is usually announced in

advance along with a target level or range at which the central

bank would like to keep the overnight interbank borrowing rate.

While the central bank may exercise the intention of moving

the overnight borrowing rate up or down it can never be sure that

it has accomplished its goal, since this rate is also affected by

market conditions which central bank economists can only forecast

imperfectly. The bank thus will often not be able to determine

whether it was responsible for moving the overnight rate in a

particular direction or whether the rate would have moved in that

direction anyway.

One way a central bank can maintain pinpoint control over the rate of

interest on overnight borrowing of reserves is to make deposits with

it the entire source of such reserves and to pay interest on those

deposits at rates that will maintain its position as the sole source

of overnight reserves. As long as it is set high enough, this interest

rate comes under the direct control of the central bank, and will be

correlated with market rates only to the extent that the authorities

manipulate it to be so correlated.

Nevertheless, the home truth is that everytime most central

banks try to manipulate their overnight rate they change the money

supply in a direction that can be predicted from its declared

intentions. And, to the extent that they control the overnight rate

directly, they can change the stock of reserves without affecting it.

By changing the official level or range for the overnight rate, a central

bank can inform the private sector of its policy intentions, whether or

not its subsequent actions actually significantly affect the rate.

Such announcement affects will affect market expectations. Changes in

bank rate perform the same function, whether or not the central bank

actually loans a significant quantity of reserves to the banking

system at that rate.

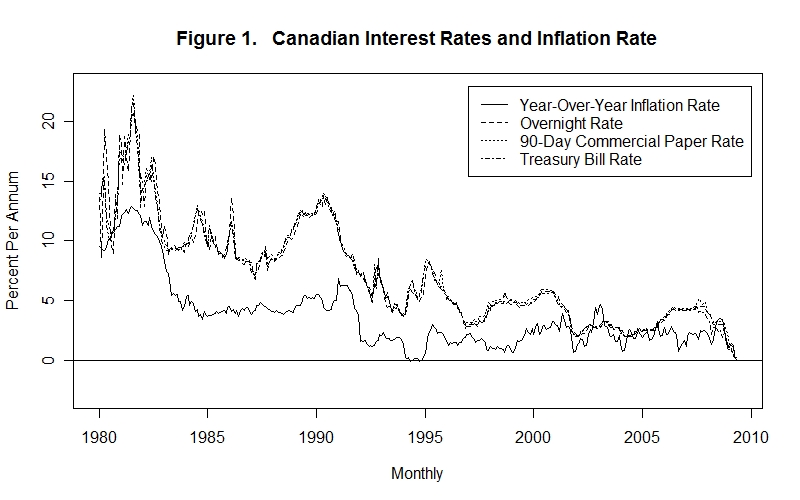

Figure 1 plots the Canadian year-over-year inflation rate together with

the interest rates on Canadian treasury bills and 90-day commercial paper and

the interest rate on overnight borrowing of reserves by the banking system.

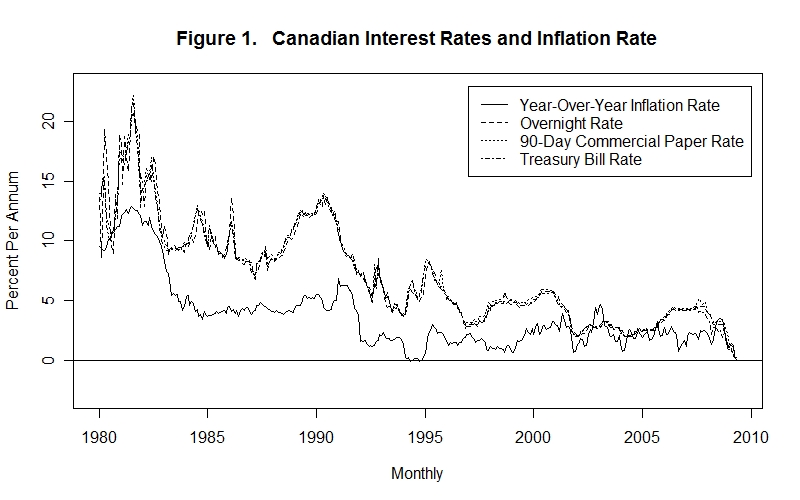

The latter rate is essentially set by the Bank of Canada. A similar plot

for the United Kindom, presented in Figure 2, presents the inflation rate

along with the interest rate on U.K. treasury bills and the official bank

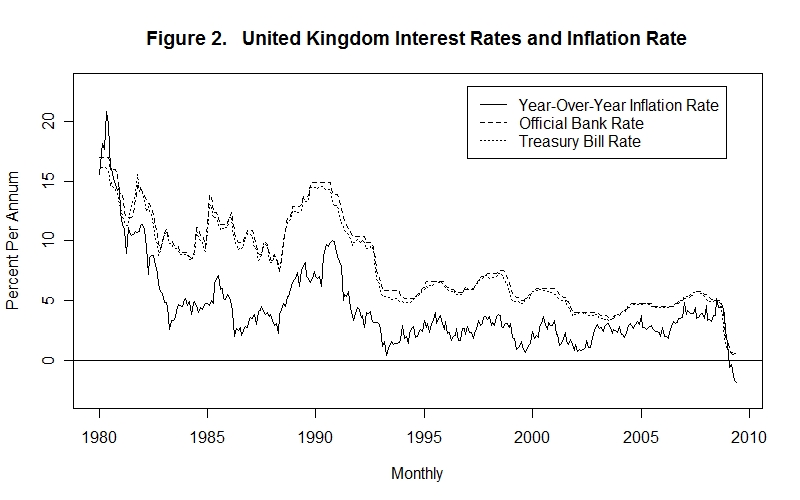

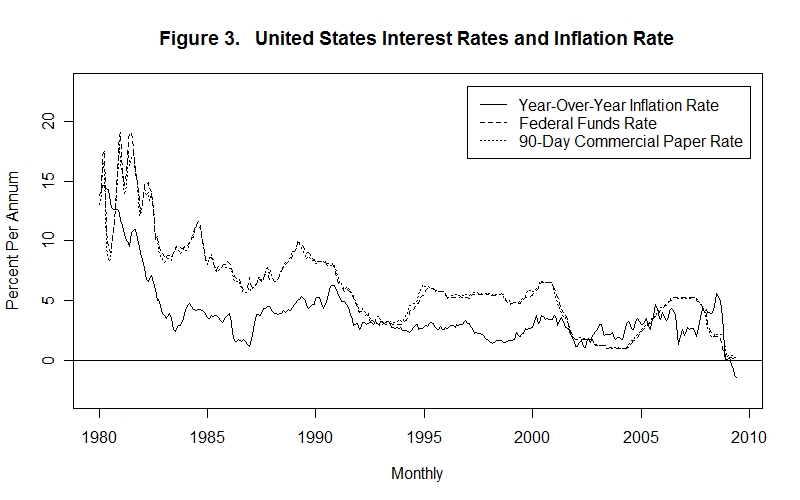

rate. Figure 3 plots the U.S. year-over-year inflation rate along with

the interest rates on U.S. treasury bills and 90-day commercial paper and

the federal funds rate, which is the interest rate targeted by the Federal

Reserve Bank in conducting U.S. monetary policy.

It should now be clear that the government of a small

open economy of the sort we have been analyzing can control that

country's nominal exchange rate and, a least for short periods,

its real exchange rate as well. Indeed the nominal and real

exchange rates are the mechanism through which monetary policy

works. Many people, including most central bankers, claim that

governments of small open economies can also control domestic

interest rates and frequently use this control in implementing

monetary policy. We now investigate these issues in more detail.

As is quite evident from the above plots, there is a strong positive relationship between each country's year-over-year inflation rate and its interest rates. Indeed the coefficients of correlation of the treasury bill rates and the year-over-year inflation rates are .826, .816, and .741 for Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States respectively. Of course, we would expect the correlations between the interest rates and the expected inflation rates, which are unobservable, to be much higher than those between the interest rates and the actual inflation rates. The differences between the interest rates plotted for each country are quite small.

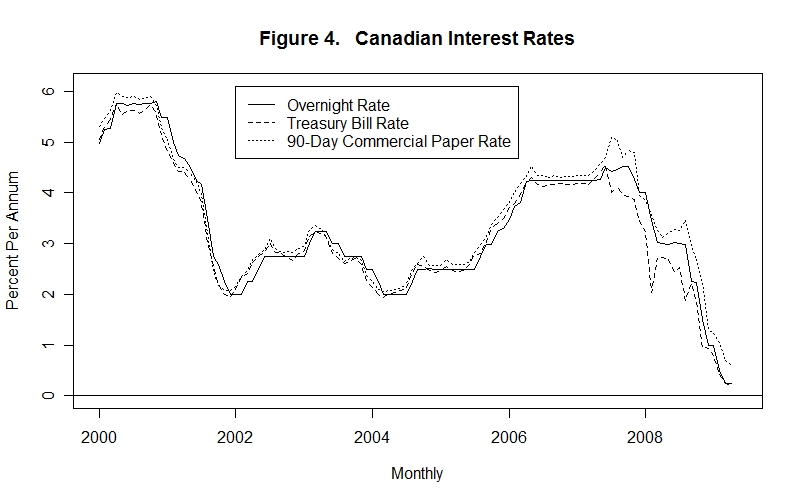

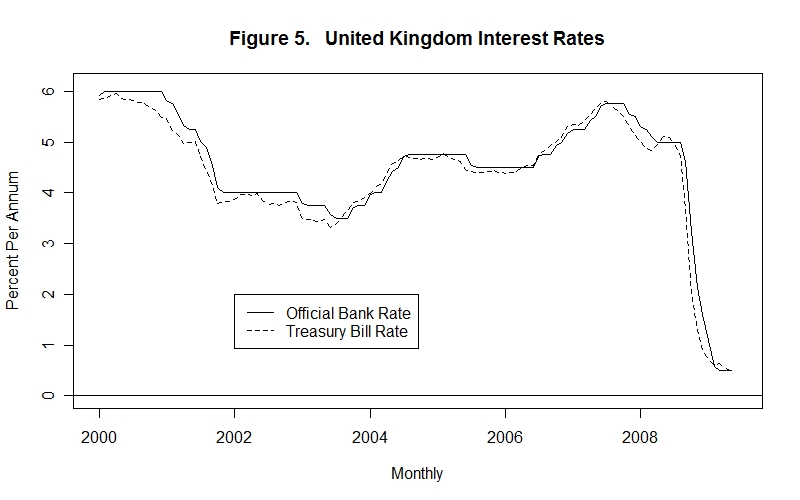

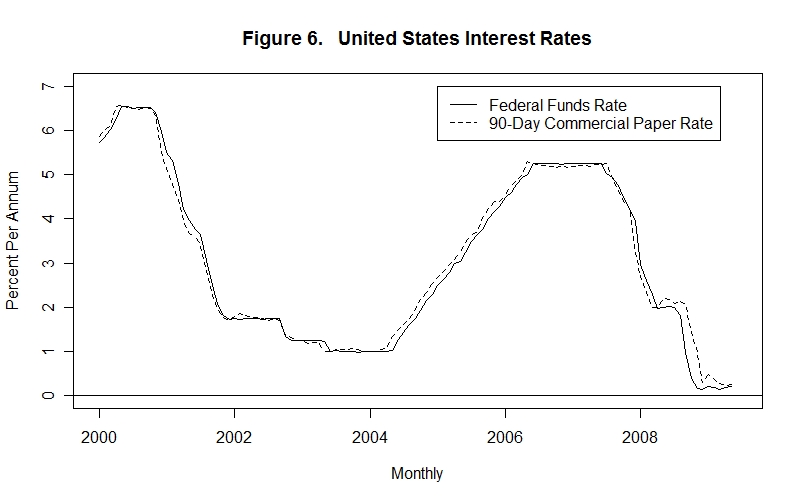

Figures 4, 5 and 6 below plot, for the past 8 years, the interest rates that the authorities of the respective countries claim to control along with the 90-day commercial paper rate in the case of the United States, the 90-day commercial paper and treasury bill rates for Canada and the treasury bill rate in the case of the United Kingdom.

Note that the Canadian commercial paper rate tends to be above that country's treasury bill rate as is consistent with the fact that corporate paper tends to be more risky than treasury bills. The interest rate on overnight borrowings of reserves, which the Bank of Canada controls, tends to be below the treasury bill rate when the latter is rising and above the treasury bill rate when that rate is falling. This would be consistent with a process whereby the Bank of Canada adjusts the overnight rate to keep it in line with market conditions rather than use of the borrowing rate to induce changes in other market rates. Indeed, given the existence of an international market for Canadian treasury bills, it is difficult to imagine how world asset holders would change their evaluation of those securities based on the interest rate on overnight borrowing of bank reserves. The only possibility would be that the Bank of Canada's adjustment of the borrowing rate would change world asset holders expectations about future Canadian inflation. There is no basis for arguing that the underlying real interest rates relevant for domestic capital investment will be affected by Bank of Canada manipulation of the overnight borrowing rate, even if that happens to involve changes in the Canadian money supply. Money supply changes would be expected to lead instead to overshooting movements in the Canadian nominal and real exchange rates, implying that the Canadian authorities should use the effects on the nominal exchange rate as a measure of the degree of expansiveness of their monetary policy---it is the effect on the real exchange rate that leads to changes in aggregate demand.

In the United Kingdom the official bank rate, which the Bank of England controls, also tends to be below the treasury bill rate when the latter is rising and above it when it is falling, as is consistent with the possibility that the authorities adjust bank rate in response to changes in market interest rates. Although the United Kingdom is much larger than Canada, it is still a sufficiently small fraction of the industrial world economy to make the real interest rate on domestic treasury bills virtually entirely dependent on world market demand---world asset holders' evaluation of the probability that Britain will default on these bills would seem unlikely to change. Of course, investors evaluation of the prospects of future British inflation may change in response to a change in the official bank rate, inducing some change in the market interest rate on the country's treasury bills. But such evaluations of future inflation will lead to a rise in the treasury bill rate in response to a reduction in the bank rate, not a fall that would be predicted to result from monetary expansion. Again, domestic monetary expansion will operate through change in the exchange rate, not reductions in the domestic real interest rates relevant for investment decisions.

Finally, it is obvious from Figure 6 that the U.S. federal funds rate, which the Federal Reserve System purports to control, also tends to be above the interest rate on commercial paper when the latter is falling and below it when it is rising---the same result as was evident for Canada and the United Kingdom. Unlike the other two countries, however, the United States has to be regarded as a major fraction of the industrial world economy. One would therefore expect that a monetary expansion in the United States would lead to some reduction in U.S. and world real interest rates. Moreover, the federal funds rate is determined in the private market and the influence of the Federal Reserve System on it is therefore not easy to measure.

Even though the U.S. is a large open economy, making its domestic monetary expansion likely to represent a significant increase in the world money supply, an overshooting response of the U.S. exchange rates with respect to other industrial countries is likely to result from domestic monetary expansion. It might be reasonable for the U.S. Federal Reserve System to simply ignore such exchange rate effects of its policies, as the external value of the U.S. dollar need not be of much concern. Such overshooting exchange rate movements should nevertheless be of concern by foreign monetary authorities as a U.S. expansion will have the same overshooting effect on their exchange rate with respect to the U.S. as would a domestic monetary contraction. If these authorities adjust their domestic money supplies to neutralize such overshooting, the world money supply will further expand as a result of the U.S. monetary expansion. In the extreme case, the world money supply will expand in the same proportion as the U.S. money supply---all countries will be following identical monetary policies, with the U.S. Federal Reserve System in charge!

Finally, let us investigate the claim that the government can control the exchange rate by simply buying and selling domestic currency for foreign currency on the international market. On the surface this seems reasonable because one should be able to affect the price of a currency by changing the supply of it going onto the market. But this will depend on the effect of the foreign exchange market intervention on the money supply.

You should recall that money supply is some multiple mm of the stock of base money H which is, in turn, the sum of its two source components, the domestic source component Dsc and the stock of reserves or foreign source component R

5. M = mm H = mm [R + Dsc]

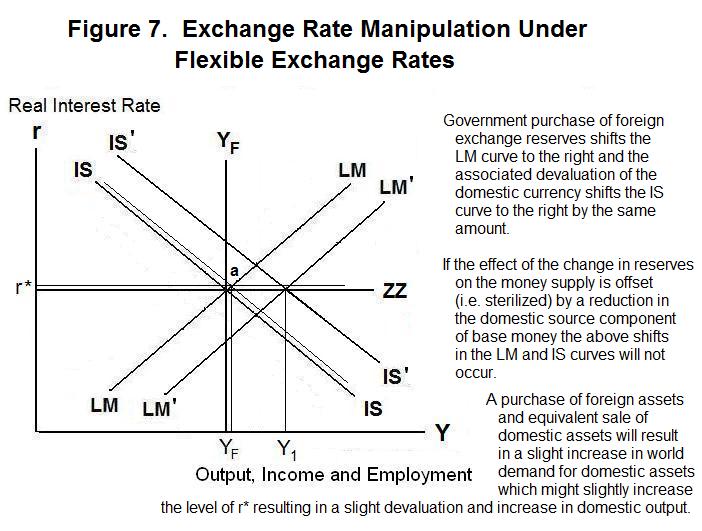

An increase in the stock of reserves will raise the money supply only if the authorities do not sterilize its effects by equivalently reducing the domestic source component. If the authorities sterilize the effect of their purchases or sales of foreign exchange reserves by open market operations in domestic bonds, so that [R + Dsc] remains constant, their actions can have no significant effect on output or prices. This can be seen from Figure 7. Equilibrium is determined by the intersection of the LM curve and the ZZ line. If the money supply does not change, neither does the LM curve and neither does the equilibrium. The nominal exchange rate that will drive IS through the LM-ZZ intersection remains unchanged.

When the government purchases foreign exchange reserves with domestic currency on the international market it increases the money supply. When it sells bonds of equivalent value it reduces the money supply by the same amount. A possible effect on the exchange rate would be a timing effect since the purchase of foreign currency occurs immediately, while the sale of foreign currency in return for domestic currency by domestic residents as they rebalance their portfolios after purchasing bonds from the government may take some time. There might thus be some temporary depreciation of the exchange rate.

Also, a sterilized official purchase of foreign exchange reserves might have a tiny effect on the domestic interest rate. The government is buying foreign assets when it increases its foreign exchange reserve holdings and selling domestic assets when it sterilizes the effect of the foreign exchange reserve increase on the domestic money supply. Since this creates an excess supply of domestic non-monetary assets on the international market, the domestic interest rate will rise relative to the foreign interest rate by a tiny amount if domestic and foreign assets are not perfect substitutes. ZZ will shift upward in Figure 7---a slightly higher domestic interest rate will now be associated with the existing world interest rate. A slight devaluation of the domestic currency will then occur to shift IS through point a .

For a significant interest rate effect to remain in the long-run, however, the risk premium on the domestic assets must permanently and significantly increase as a result of this portfolio shuffle. Since, for changes in foreign exchange holdings of the magnitude normally experienced, the substitution of domestic for foreign assets will be an extremely small fraction of the world asset portfolio, the effect on domestic relative to foreign interest rates, the exchange rate and domestic output will surely be minuscule.

Of course, if the effect of an increase in official foreign exchange holdings on the money supply is not sterilized by an open-market operation in domestic bonds, the domestic money supply will increase and the LM curve will shift to the right. Employment and/or prices will increase, when the exchange rate is flexible, in the same manner as would have occurred from any increase in the money supply, no matter how it was generated.

Time for a test. Make sure you think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.