Now we can put the tools developed in the previous two

topics together to discuss, at a rudimentary level of course,

what might be socially optimal. In any discussion of what is

or might be good or bad from the point of view of society as a

whole, the economist is limited to commenting on issues of

efficiency. Though economists may be able to say something

about how a particular policy might affect the distribution of

income among the members of society, economics provides no

insights on whether a particular distribution of income is

good or bad---this requires value judgements.

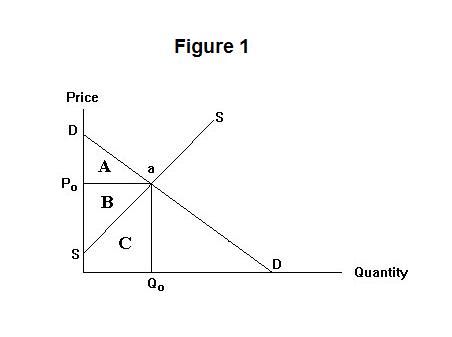

Figure 1 can refer to any particular commodity or service

for which the supply curve slopes upward and the demand curve

downward.

The free market equilibrium price and quantity are P0 and Q0. We have noted that the total benefit to the purchasers of the good is the area under the demand curve to the left of Q0---the sum of the areas A , B and C. And the marginal benefit at output Q0 is the distance Q0 a. The alternative opportunity cost of producing output Q0 is the area under the supply curve---denoted by C. And the marginal opportunity cost of producing the output Q0 is also the distance Q0 a. If there are no consumption externalities, the net benefit to society from having the quantity Q0 rather than none at all is the area under the demand curve and over the supply curve---area A plus area B. The area A is the consumer rent or surplus and the area B is the producer surplus or rent.

The output Q0 in the above Figure would appear to be the socially optimal output in the sense that the gains to the purchasers net of the opportunity costs are maximized. These gains are maximized when the marginal social benefit from having another unit of output equals the marginal social opportunity cost and when the area under the demand curve and over the supply curve is thereby maximized. If output were reduced below Q0, some of these net gains would be lost. Losses would also result if output were expanded beyond Q0. The marginal opportunity costs of producing output beyond this point would exceed the marginal benefits.

We cannot guarantee, however, that when output is increased to Q0 from below that level everybody in the society gains the same amount---indeed, normally some people will not gain at all. What can be said is that there is an opportunity for everyone to gain. The appropriate division of these potential gains as well as the final decision to go after them are issues beyond the purview of economic analysis. But sensible people prefer more to less if a way can be devised to achieve it, so the economist's insights here are of considerable value.

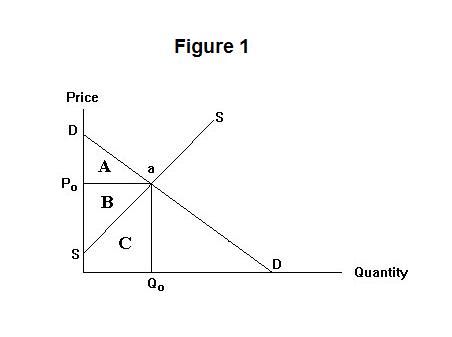

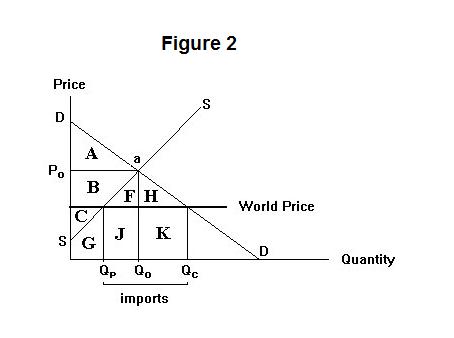

These issues become front and center when we now introduce the possibility that the residents of this country or local area can purchase and sell the commodity in question on the world market at a fixed price. This world price is given by the thick horizontal line in Figure 2.

Starting from the initial quantity Q0, demanders will find it worthwhile to increase the quantity they purchase to Qc. They will pay an amount equal to the sum of the areas C, G, J and K for this quantity and their gross benefit will now be the area under the demand curve to the left of Qc rather than the area to the left of Q0. They will be better off on net because their surplus or rent will increase by an amount equal to the sum of B, F and H.

Producers will now find that they can no longer sell their output at price P0 and are forced to take the world market price instead. At that price it will be profitable to produce only Qp. Their surplus or rent will fall to the area C and they will be worse off by the area B. So producers will be against the introduction of foreign competition.

Notice, however, that consumers gain the sum of areas B, F and H while producers lose only area B. There is a net gain to society in the sense that consumers could bribe producers by giving them the amount B and still be better off by the sum of areas F and H.

Notice that people in the area consume output Qc and produce output Qp. The excess of Qc over Qp, is imported from the rest of the world. Domestic consumers now pay the amount C + G to domestic producers and the amount J + K to foreign producers, whereas previously they paid the sum of areas B, C, G, J and F to domestic producers. When we to take into account all goods in the world economy, not just this one, it turns out that the payment to foreigners, J + K, will be matched by equivalent earnings from additional exports of other goods to the rest of the world. Domestic resources are shifted out of production of the imported good and into the production of other goods that will be exported while domestic purchases are shifted away from those other goods in order to buy more of the imported good.

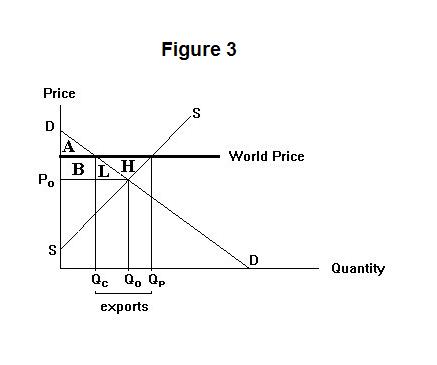

A similar gain from trade arises when the world price is above the free market price, as shown in Figure 3.

In this case production expands and consumption contracts. Producers gain the area B + L + H and consumers lose the area B + L, with a net gain equal to the area H. The excess of Qp over Qc is exported.

The fact that domestic consumers gain the area B + F + H while domestic producers lose only the area B in Figure 2 and producers gain the area B + L + H while consumers lose only B + L in Figure 3 indicates that there is a gain from trade in the sense that it is possible to go from zero international trade in this commodity to free trade and make everyone better off---all that is necessary is a payment to producers by consumers somewhat in excess of the area B in Figure 2 or a payment to consumers by producers somewhat in excess of B + L in Figure 3. The difficulty is, of course, that such compensating payments are almost never made. The move to free trade therefore benefits part of the community and hurts another part, even though in dollar terms the benefits exceed the hurt.

This means that the losers from free trade will vigorously oppose it---resources will be used up trying to convince the government and the public which it represents that free trade in the circumstances at hand is bad. Gainers, on the other hand, will devote resources to demonstrating that free trade is good. Economists call these activities rent seeking. The resources spent in political conflict over rents could be used to produce goods for current consumption or for investment in capital goods that will help produce more future consumption.

Most frequently in the case where imports displace domestic production the losers from free trade are a small group of producers, each of whom stands to lose a significant amount. On the other hand, the gainers consist of many consumers who individually gain very small amounts. The gain might be $550,000 split among one million consumers (amounting to 55 cents per consumer) while loss might be $500,000 split among 20 producers (amounting to $25,000 per producer). Producers thus have a strong incentive to form a trade association and take up the fight, while most consumers probably don't even know they gain from trade. The fact that the gain here to individual consumers is too small to be noticeable makes them vulnerable to carefully crafted arguments from producers suggesting that free trade is costly rather than beneficial---a proper evaluation of these arguments is not worth individual consumers' time. As a result, most societies frequently end up not only loosing gains from trade, but wasting additional resources in rent seeking activities designed to convince everybody that free trade produces losses rather than gains.

The gain from trade is an efficiency argument. Through free trade, everyone can have more. If we cannot handle the distribution effects, however, and really make everyone better off, is efficiency worth pursuing? Potential efficiency gains and losses appear all over the economy, not just in situations involving free vs. restricted trade. Every pursuit of an efficiency gain hurts someone, albeit by less than others gain. If potential efficiency gains are always pursued, most people will gain on some occasions and lose on others. On average nearly everyone will gain. Those few who end up in a clearly losing position can be compensated.

Despite this, it is in every individual person's interest to fight hard to preserve those inefficiencies from which he or she benefits---in each individual circumstance a gain is to be had regardless of what happens to everyone else. Unfortunately, a social contract in which we all agree to permit the unfettered pursuit of economic efficiency, in return for a promise of compensation if we happen to be among the few who end up losing significantly on balance, is impossible to enforce.

It is test-time again. As always think about your answers carefully before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.