In this Topic we take a close look at these theories. Since

competitive firms take market prices as given, there is no way that

they can raise prices to cause inflation---all price increases must

result from either a shift of demand or an increase in costs.

For firms to be able to set prices they must have monopoly

power. Let us therefore assume that all firms in the economy are

monopolies and see what can be concluded in this extreme case

about their contribution to inflation. For monopoly firms to cause

inflation they must, as claimed, greedily raise prices again and again

to profit at the expense of the community.

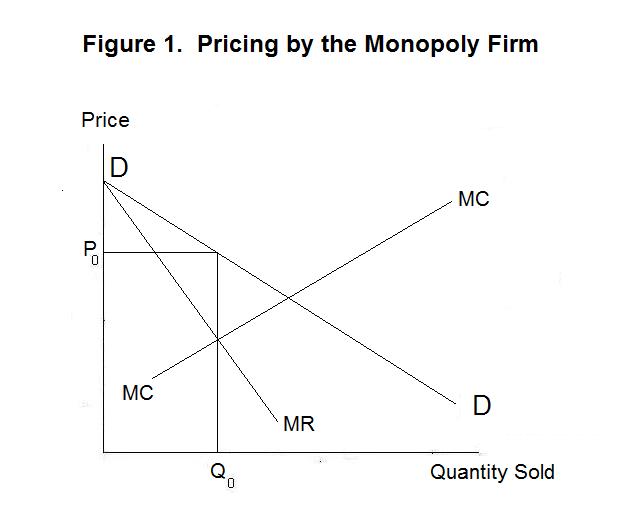

The place to start is with an analysis of how monopoly firms

set prices. Being greedy, they will maximize their profits. So

they will only change the prices they charge if the gain in total

revenue from such a change exceeds the increase in total costs---otherwise,

profits would fall. Given a negatively sloped demand

curve for their product, firms can only change their selling price

by adjusting the quantity of output they produce and sell.

The increase in total revenue from selling another unit is the marginal

revenue and the increase in total cost is marginal cost.

Accordingly, profit will increase when output is contracted and the

price rises only if marginal revenue is less than marginal cost.

This can be seen from Figure 1.

It is almost inevitable in situations of persistent inflation

that blame will be attached to workers and/or firms. Obviously,

it is workers and firms that actually raise prices. This prompts

what might be thought of as a greed theory of inflation---inflation

results when workers and firms, greedy for increased shares of the

national output, continuously push up wages and prices. The remedy

is for the government to set up an anti-inflation board that will

allow only those wage and price increases that are in the national

interest. Inflation driven by the pricing behaviour of workers and

firms is commonly termed cost-push inflation which results,

it is claimed, from the pass-through of higher wages and profit margins

into final product prices.

The demand curve for the firm's output is given by the curve DD. The curve relating the firm's marginal revenue to its output, shown as MR in Figure 1, will touch the demand curve when output is one unit because the increase in total revenue from selling that unit is the price obtained for it. At higher output levels MR must lie increasingly below the demand curve. The gain in revenue from selling another unit is increasingly less than the price obtained for that unit as more and more units are sold because the price obtained for all previous units falls as the quantity increases, given the demand curve's negative slope. Marginal revenue falls more rapidly than the price as the quantity sold increases.

The firm's marginal cost curve, MC, will typically be upward sloping to the right. As the firm produces more and more output, each additional unit adds more to costs than the previous unit because there are usually diminishing returns from the application of labour and capital to a fixed stock of organizational or entrepreneurial ability. As the firm gets larger and larger it becomes more and more difficult to manage and control. Our conclusions below will be the same, however, if it turns out that the firm's marginal cost curve is a horizontal line and costs are constant with respect to output.

Since the firm will increase its output if marginal revenue exceeds marginal costs (total revenue rises more than total cost so profit increases) and reduce its output if marginal revenue is less than marginal cost (total cost falls more than total revenue so profit increases), equilibrium will occur at output Q0 where marginal revenue equals marginal cost. This will happen as long as the firm is greedy and not stupid. The firm's total cost curve, which is not shown in Figure 1, must also be low enough that total profit is not negative---we assume this to be the case because otherwise the firm would not be in business.

It should now be obvious that the greedy firm has no incentive to increase its selling price above P0 unless its demand curve shifts to the right or its cost curve shifts up. It does not pay the firm to keep increasing prices because doing so will lower its profits, not increase them. Assuming that the money supply does not increase and the demand for money does not decrease, so that aggregate demand in the economy remains constant, greedy behaviour on the part of firms cannot cause inflation. The greed theory fails because it is not in greedy firms' interest to continually raise prices.

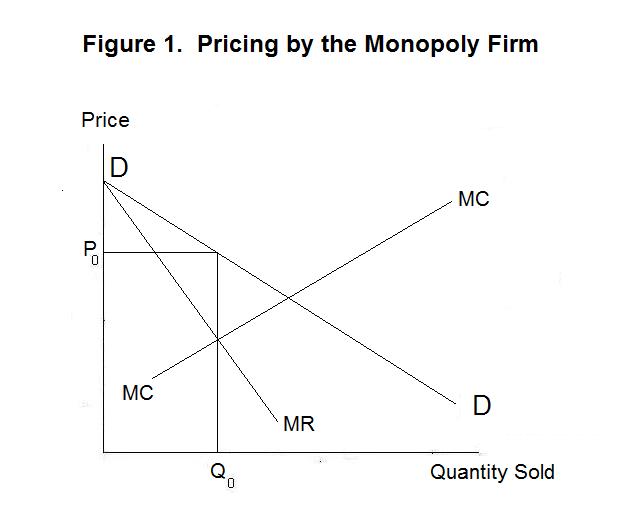

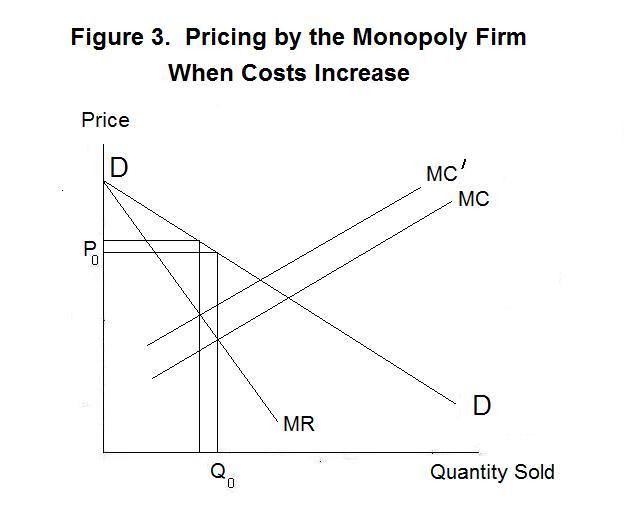

Of course, if the demand curve shifts to the right the firm will increase its selling price, as shown in Figure 2. But for the demand for the outputs of all firms to increase there must be an increase in aggregate demand for output in the economy and, hence, in the equilibrium price level. This can only happen if the demand for money declines or the government increases the supply of money too rapidly.

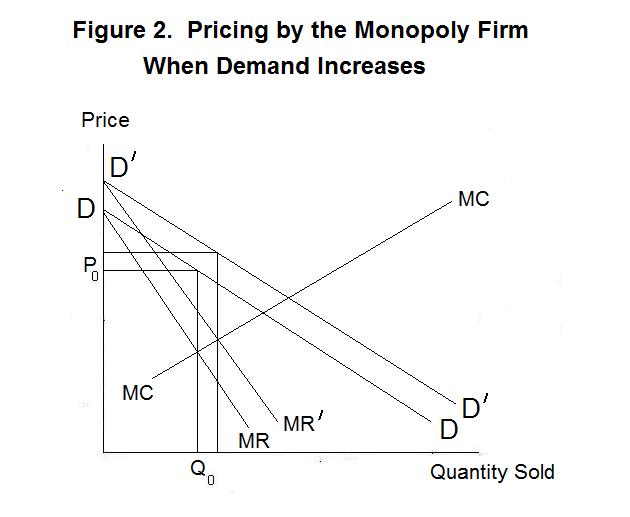

Also, the firm will keep increasing its selling price in the absence of a rightward shift of the demand curve if its costs keep rising, shifting MC upward as shown in Figure 3. This can only happen for all firms in the economy if the wages paid to workers are continually being pushed up by labour unions without regard to the demand conditions for labour.

So the question now arises as to whether labour unions, acting on behalf of greedy workers, will cause inflation by continually pushing up wages and labour costs that firms are forced to pass on in the form of higher prices. Again, we take the extreme case, assuming that the entire economy is unionized.

It might seem in the interest of workers for unions to force up wages continuously---after all, everyone wants higher wages! It is easy to show, however, that this is not the case. The reason is that the demand curve for labour is negatively sloped.

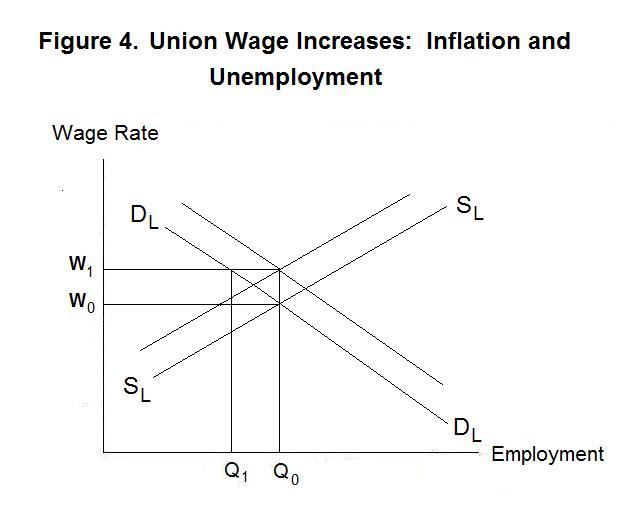

As we shall argue in more detail in the next Lesson entitled Unemployment, the demand curve for labour in any industry and in the economy as a whole is negatively sloped for two reasons. First, a rise in the wage rate increases costs and causes firms to reduce output---this reduces the quantity of labour that firms can profitably employ. Second, an increase in the wage rate makes labour more expensive relative to capital, causing firms to substitute capital for labour and further reducing the quantity of labour employed. Every union thus faces a trade-off between higher wages and lower employment in its industry as shown in Figure 4. By forcing up the wage rate it puts some of its members out of work.

Choosing the best wage for its workers is a difficult task for every union. Since the union members ultimately choose the policies their unions follow they must somehow jointly choose the level of wages the union will agree to. However this is done, it is not in the interests of workers, given a stable demand curve for labour, to push wages up indefinitely. At most, it would be in workers' joint interest to set the wage rate at the level at which the elasticity of demand is unity and total wage payments by the firm are therefore maximized---those who remain employed can then compensate those driven out of work and the average earnings of all union members, working or not, will be maximized.

Unless the government forces firms to use only unionized workers, those workers forced out of employment by high wages will have an incentive to seek employment with non-unionized firms who will then be able to out-compete the high-wage unionized ones. And even if the government forces all firms to use only unionized workers, those workers displaced by high-wage unionized firms can form their own unions and charge wages low enough to obtain employment. Unions thus cannot force wages continually upward without direct wage-setting by the government. And the government has no incentive to create unemployment by fixing wages at a level it is not willing to finance with an appropriate money supply.

Consider the situation in Figure 4 which represents the market for labour in the economy as a whole. Suppose that unions bargain the wage up to W1 from W0. Employment falls as a result from Q0 to Q1. The government can restore full employment by increasing the money supply in proportion to the increase in wages. This will increase the equilibrium price level in the same proportion so that the real wage rate will return to its original level. Both the demand and supply curves for labour will shift up in proportion to the increase in the price level and the increase in nominal wages achieved by the union. If the government chooses not to finance a higher price level, employment will necessarily fall with a rise in the wage rate. If it provides the money supply to finance the new level of money wages at full employment, then the union will not have successfully increased real wages.

It is clear that unions have no incentive to increase wages without limit if the government refuses to provide the monetary finance. And the government has no incentive to finance union wage escalation because the only real consequence will be inflation. And were the government to provide the finance, the unions have no incentive to keep increasing nominal wages because they are achieving no increase in real wages.

If the government maintains a stable monetary policy, there is no benefit to workers from continual increases in wages in excess of the growth of labour's productivity. If the government does not conduct a stable monetary policy, nominal wages will continuously rise with the resulting inflation while workers will always pay for any increase in real wages through reductions in the level of employment.

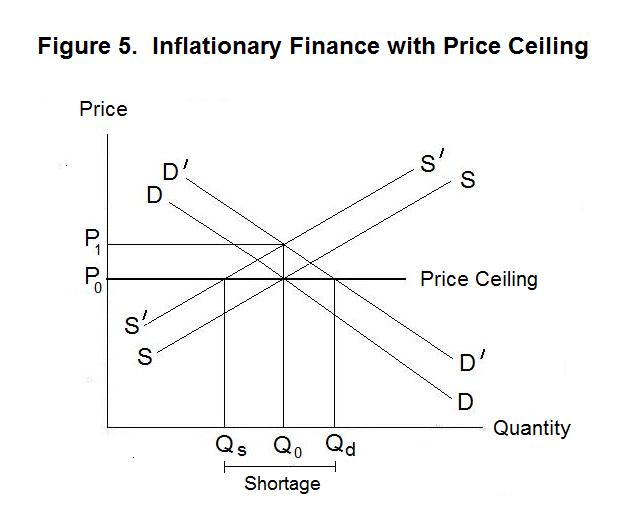

It can thus be established that ongoing inflation cannot be caused by the price setting behavior of workers and firms---it can only arise from excess monetary expansion by the government. It follows that policies designed to eliminate inflation by fixing wages and the prices firms can charge are inappropriate. The effects of such policies can be seen with reference to Figure 5.

We can let DD and SS be the demand and supply curves for a typical commodity in the economy. When the government expands the money supply and the equilibrium price level rises, all supply and demand curves shift up vertically, with the price rising from P0 to P1 and quantity remaining unchanged. If the authorities try to eliminate this inflation by fixing the price at P0, they simply create a shortage in the amount Qd − Qs.

By fixing prices in the face of excess monetary expansion, the government masks the underlying inflation by creating shortages in every market in the economy. This leads to black market dealings and long queues that cause time and effort to be spent standing in line and working around the price ceilings rather than producing useful goods and services.

It is now time for a test. Be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson