We begin by assuming a world of two equal-sized countries

in which one country pegs its currency to the currency of the

other country. The former country can be viewed as an aggregate

of many small peripheral countries.

Note immediately that this system requires that there be

only one authority that fixes any exchange rate. If both countries'

authorities try to independently fix the exchange rate between the two

currencies at different levels they will provide unlimited profits to

arbitragers who will buy from one authority and sell to the other. When

one country pegs its currency to the currency of another, the latter must

act as though it does not care about the level of the exchange rate.

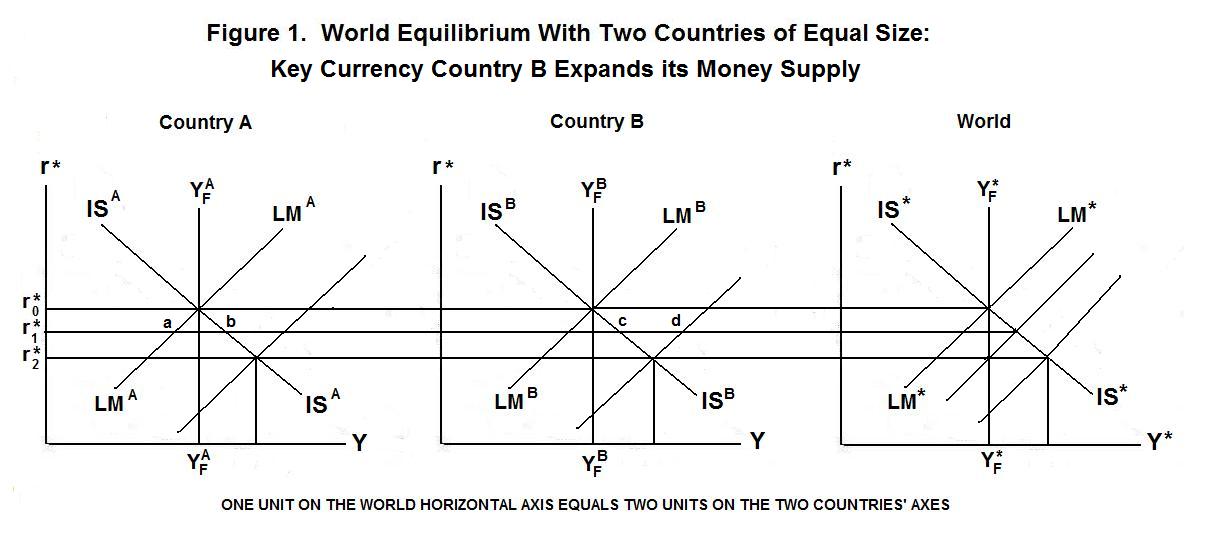

Suppose that Country A pegs its currency to the currency of

Country B. The latter then becomes the key-currency country and

its currency becomes the key currency. Short-run equilibrium

occurs when both countries' IS and LM curves, and

the world IS and LM curves, cross each other at the

same world real interest rate. Long-run equilibrium occurs when those

intersections also occur on the respective countries' vertical

full-employment lines. This is shown in Figure 1 at the world real

interest rate r0*.

When all countries adopt a gold standard the world has,

in effect, a common currency consisting of gold or claims on

gold. A common currency system could also be created by having

an internationally controlled central bank create a paper currency to

which all other countries fix their exchange rates. We now examine an

alternative fixed-exchange-rate system in which all countries save one

peg their currencies to the currency of the remaining country.

An example is the Bretton Woods system, in effect from after World War II

until the early 1970s, where most of the world's currencies were pegged

to the U.S. dollar.

Under a common currency system all countries peg their currencies to a

single commodity or paper currency whose quantity is independent of the

actions of any country. The world money supply is determined by gold

discoveries and the cost of mining gold (in the gold standard case) or

by the actions of an independent world central bank (in the case of a

paper currency). Under a key currency system, one country's currency

becomes the world monetary standard.

Now suppose that there is a monetary expansion (or other positive monetary shock) in Country B, the key-currency country. LMB shifts to the right. Since Country B comprises half of the world, the world LM curve shifts to the right by half the rightward shift of LMB. The world real interest rate falls to r1*. At that world real interest rate there is excess demand for money in Country A equal to the distance a b and excess supply of money in Country B equal to the distance c d. A-residents will sell non-monetary assets to B-residents and the authorities in country A will increase A's money supply as they add to their B-currency-denominated reserves to keep their currency from appreciating.

Country A is sufficiently large that an increase in its money supply will significantly increase the world money supply, further driving down the world real interest rate and reducing the excess demand for money in Country B. Since B's IS and LM curves are unaffected as portfolio equilibrium is re-established in A, this process will continue until the world real interest rate has fallen sufficiently to pass through the intersection of Country B'as new LM curve with its IS curve. The world real interest rate will fall to r2* and output will increase in both countries.

The equilibrium world real interest rate is thus determined by the intersection of the IS and LM curves in the key-currency country. The money supply in the other country---that is, the peripheral country---will adjust automatically as that country's authorities buy and sell foreign exchange reserves, which consist of short-term key-currency-denominated assets, to maintain the fixed exchange rate. These adjustments of the peripheral country's money supply change the world money supply to produce the equilibrium world real interest rate. In the process, the peripheral country's authorities are induced to produce exactly the same monetary shocks as occur in the key-currency country. The key currency country can conduct its monetary policy as though it were the only country in the world.

In the long run, wages and prices will rise in both the key-currency and the peripheral country, shifting their LM curves back to their original positions and the world real interest rate back to its original position. Since nothing happens to affect the real exchange rate, and the nominal exchange rate is fixed, both countries' price levels must rise in the same proportion. By fixing its exchange rate, the peripheral country adopts the key-currency country's monetary policy, with whatever consequences that might entail for domestic output and inflation.

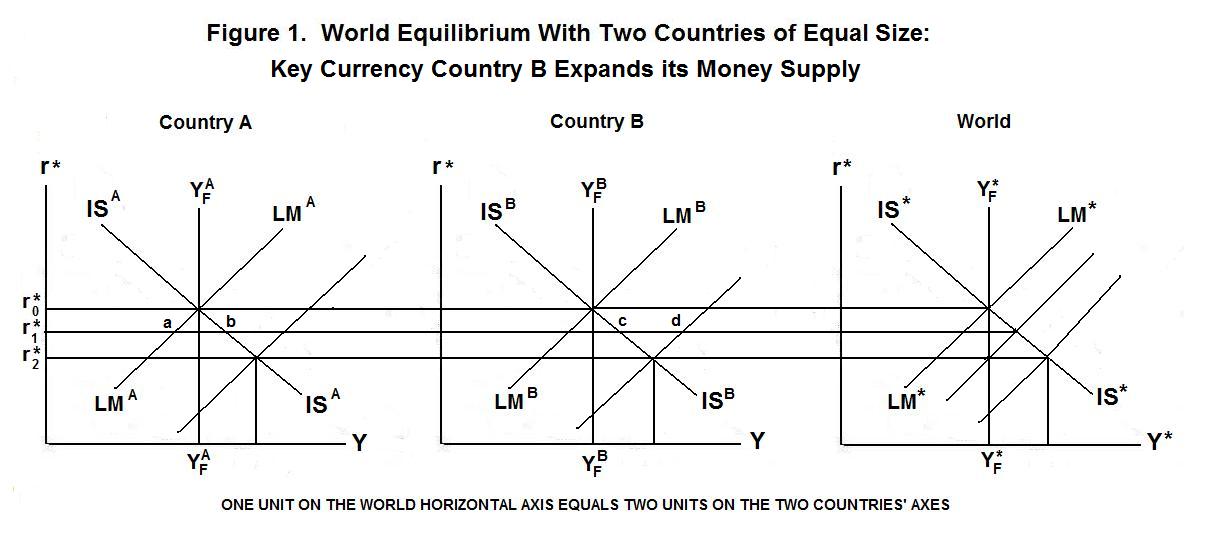

It is easy to see that if the peripheral country were to try to conduct an independent monetary policy, shifting LMA to the right, it would create excess money holdings which domestic residents would exchange for foreign assets. To maintain the fixed exchange rate, its authorities will have to buy back those excess money holdings in return for foreign exchange reserves, maintaining LMA in its initial position. Monetary policy is impotent in the peripheral country. This is shown in Figure 2.

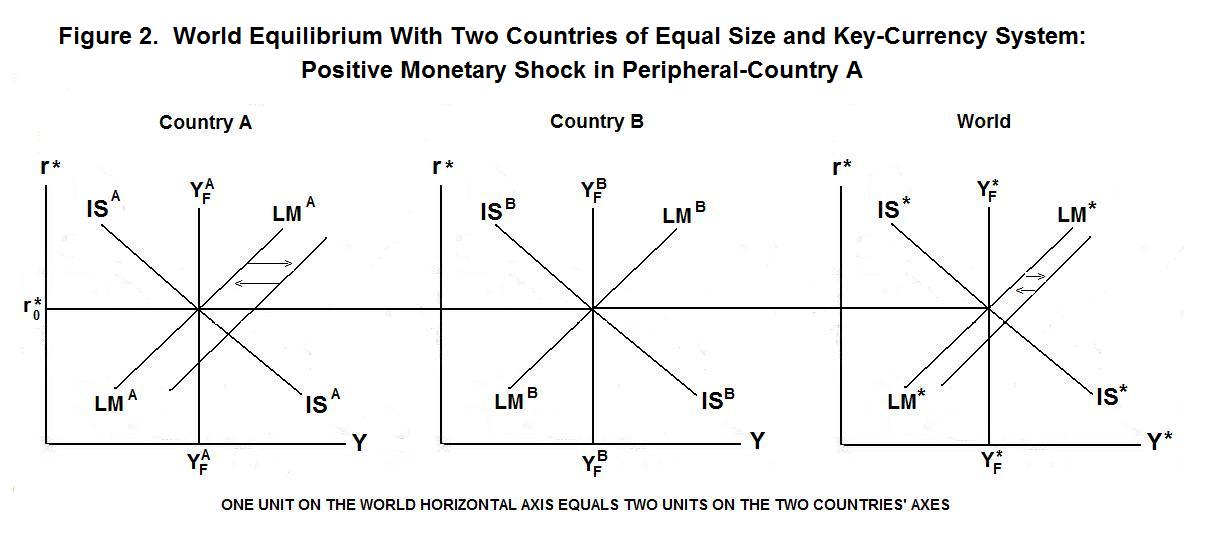

Now suppose that Country B, the key-currency country, conducts an expansionary fiscal policy, shifting ISB to the right in Figure 3. To the extent that the additional demand for goods in Country B bleeds through into Country A, ISA will also shift to the right, but by a smaller amount than the rightward shift of ISB. The world IS curve will shift to the right by less than the shift in ISB but more than ISA. This will increase the world interest rate as shown in Figure 3.

An excess demand for money will occur in Country B since its LM curve now crosses the new interest rate line to the left of its IS curve and an excess supply of money will occur in Country A since its LM curve now crosses the new interest rate line to the right of its IS curve. A-residents will buy non-monetary assets from B-residents and Country A's central bank will be forced to reduce the money supply in A, shifting LMA to the left. This will reduce the world money supply, shifting LM* to the left and further raising the world real interest rate to r1*, with the world equilibrium at point a in Figure 3. Output and employment increase in Country B and in the world as a whole but, in the particular example shown, decline in Country A.

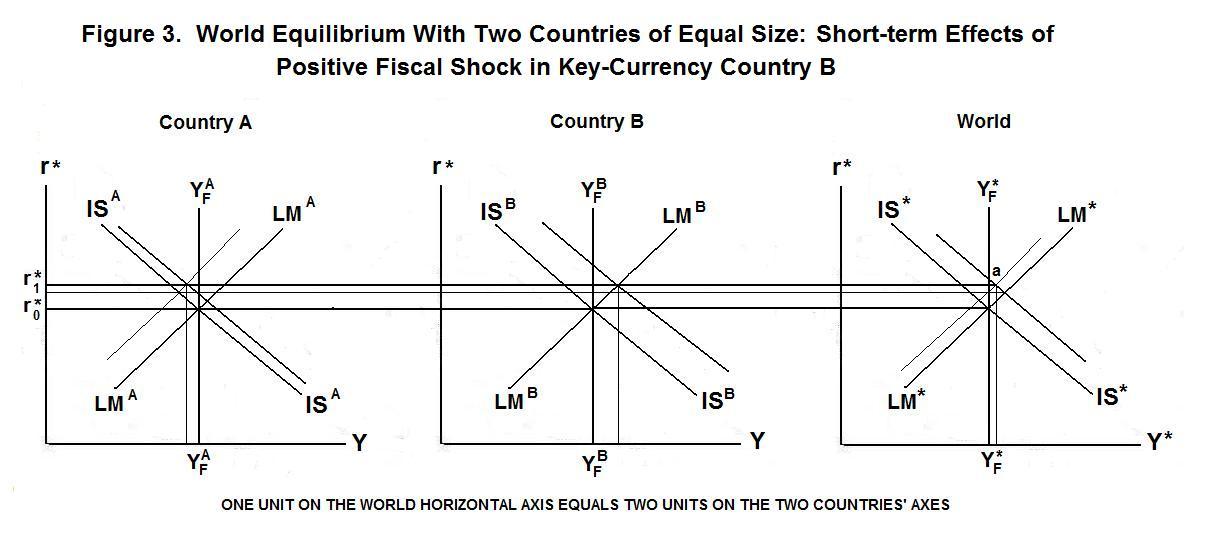

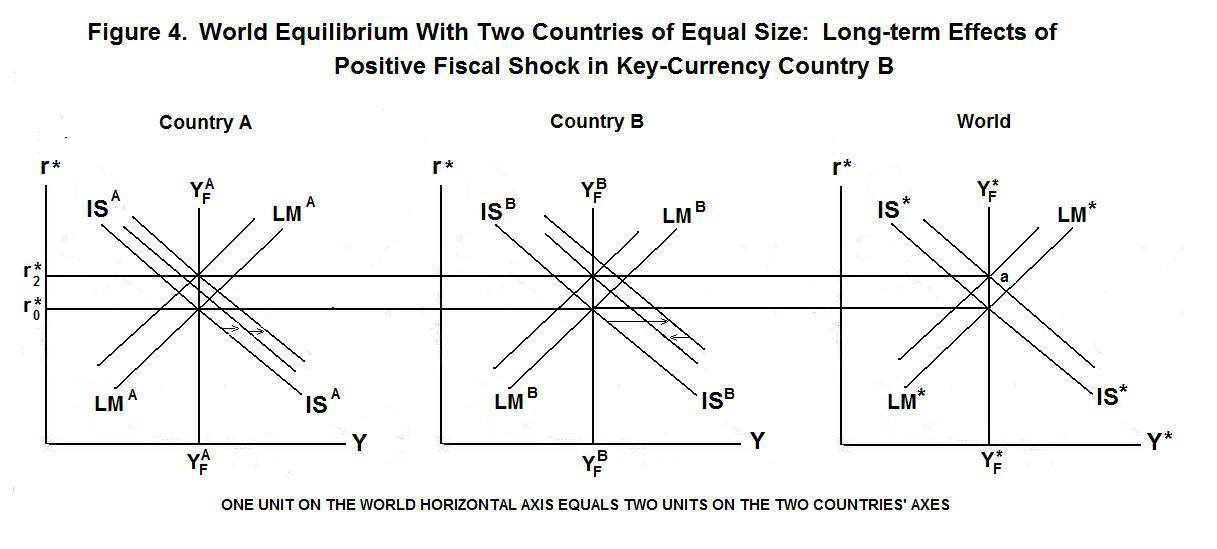

In the long run, wages and prices will rise in Country B. In the absence of a similar rise in the price level in Country A, this will represent a decline in A's real exchange rate which will shift A's IS curve to the right and B's IS curve to the left. The world IS curve will be unchanged because the change in the real exchange rate simply reallocates the existing level of world aggregate demand among the two countries. An unchanged level of the world IS curve in the long run, together with unchanged levels of full-employment output in both countries, implies that the final equilibrium world real interest rate must be at point a in Figure 4. To avoid clutter, the LM curves depicting short-run world equilibrium are not labelled. The arrows on the separate country graphs indicate the short-run followed by the long-run effects---Country B's IS curve shifts to the right in the short-run and then to the left by a smaller amount in the long run. Country A's IS curve shifts to the right in the short run and then further to the right in the long run. Country A's real exchange must have fallen in the long run to shift its IS curve further to the right and Country B's IS curve to back to the left to pass through their respective full-employment output lines at the horizontal world interest rate line at the final equilibrium world interest rate r2*.

Given the fixed nominal exchange rate, Country B's price level must rise relative to Country A's because Country A's real exchange rate has to fall to move Country B's post-shock IS curve leftward in the long run. This is required because the fiscal policy in Country B shifts that country's IS curve further to the right than it shifts the world IS curve.

A positive fiscal shock in the key-currency country thus leads to an increase in its output and employment in the short run and an increase in its price level in the long run. The peripheral countries, the aggregate of which is represented by country A in the analysis above, may experience negative effects on their employment and income in the short run. In the long run their real exchange rates with respect to the key-currency must fall as the key-currency country's price level rises relative to their own price levels, which may change in either direction.

We could now go on to analyze the effects of fiscal policy in the peripheral countries. But this would be of little practical interest because peripheral countries are usually small and their fiscal policies uncoordinated. As a result, a fiscal shock in a small peripheral country will have no significant effect on the key-currency country, which is usually large, or on the rest of the world. The same situation holds for commercial policies and exchange rate devaluations in peripheral countries. The domestic effects of these policies can be analyzed using standard small open economy analysis and the effects on the rest of the world are negligible unless a group of peripheral countries devalue their currencies or impose tariffs in a coordinated fashion.

A careful analysis of the effects of a peripheral country's tariffs or a devaluation of its currency a two-country world where the peripheral country is large would be an interesting exercise to sharpen your understanding of the analytical techniques applied in this module.

It's time for a test. Remember t think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.