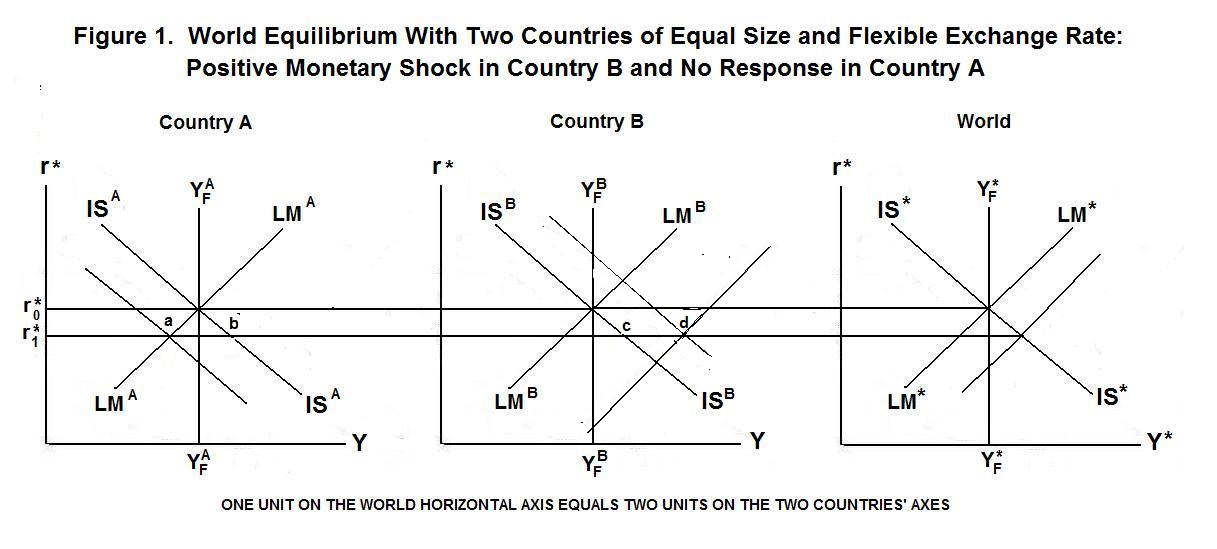

The analysis begins with reference to Figure 1. Suppose

that Country B increases its money supply,

shifting LMB to the

right. The world LM curve shifts to the right by half the amount

that LMB shifts, given that B is half the size of the

world. These new curves are the solid unlabeled curves in Figure 1. The world

interest rate falls to r1* leaving an excess supply of

money in Country B equal to the distance c d and an excess

demand for money in A equal to the distance a b. B-residents

will try to buy assets from A-residents, causing B-currency to depreciate.

This will shift ISA to the left

and ISB to the right.

We end this lesson with a consideration of how monetary and

fiscal policy work in a big open economy when exchange rates are

allowed to float. The effects of these policies in the big country

depend on how other countries manage their money supplies in

response to the consequences of those policies for their income,

employment and prices. As in the previous topic, Country B is a big

country following independent monetary and fiscal policies. Country A is now

a rest-of-world-aggregate, equal in size to Country B, that can

use monetary policy to manipulate the exchange rate(s) of its

currencie(s) with the currency of Country B.

Assuming that Country A holds its money supply constant and Country B maintains its money supply at its new higher level, B-currency will depreciate until ISA passes through point a and ISB passes through point d. Income and employment will fall in Country A and rise further in Country B. By holding its money supply constant in the face of monetary expansion in B, Country A loses income and employment and magnifies the short-run income and employment gains in Country B.

In the long run Country B's price level will rise, shifting its LM curve back to its original position and returning the world real interest rate to r0*. As Country B's price level rises relative to the price level in Country A, the real exchange rate returns to its initial level, shifting Country A's IS curve back to the right and Country B's IS curve back to the left. In the end, the price level in Country B will have risen and the nominal value of its currency will have fallen in proportion to the increase in that country's money supply, with all real variables, including the real exchange rate, returning to their original levels. Since Country A's LM curve remains at its original level its price level is unchanged.

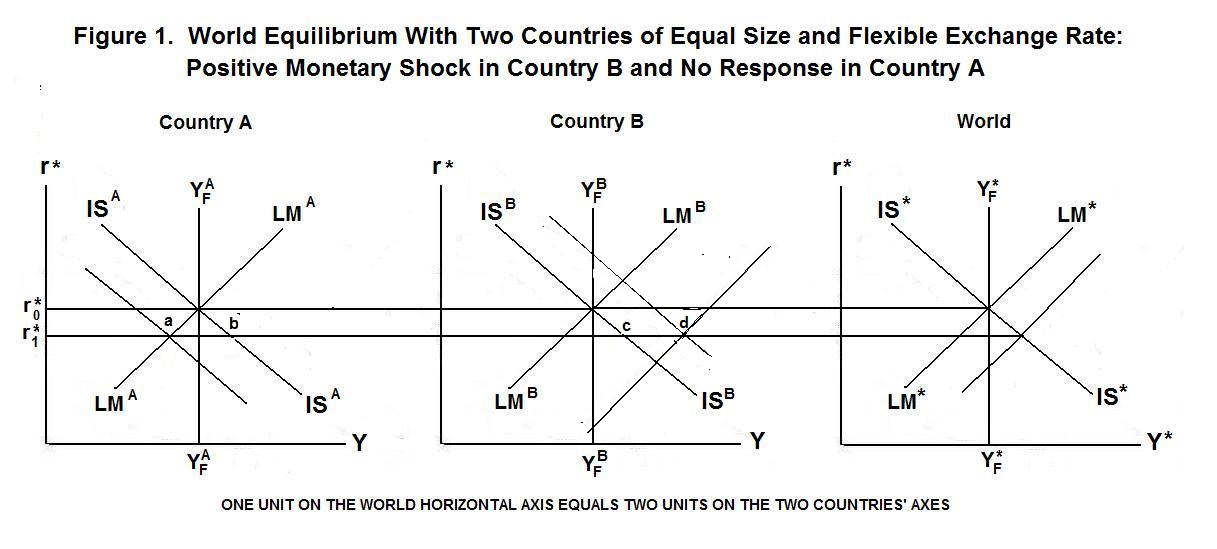

Policy-makers in the countries comprising the aggregate we define as Country A, if they know what is going on, are not likely to stand still in response the adverse effects of the monetary expansion in Country B. Suppose that they adjust their money supplies to prevent B-currency from depreciating. The result, shown in Figure 2, is the same as occurs when country B is given the key-currency role. The world real interest rate falls to r2* and Country A's income and employment and, in the long run its price level, move identically with Country B's. The A-Countries now end up mimicking the monetary shocks in B.

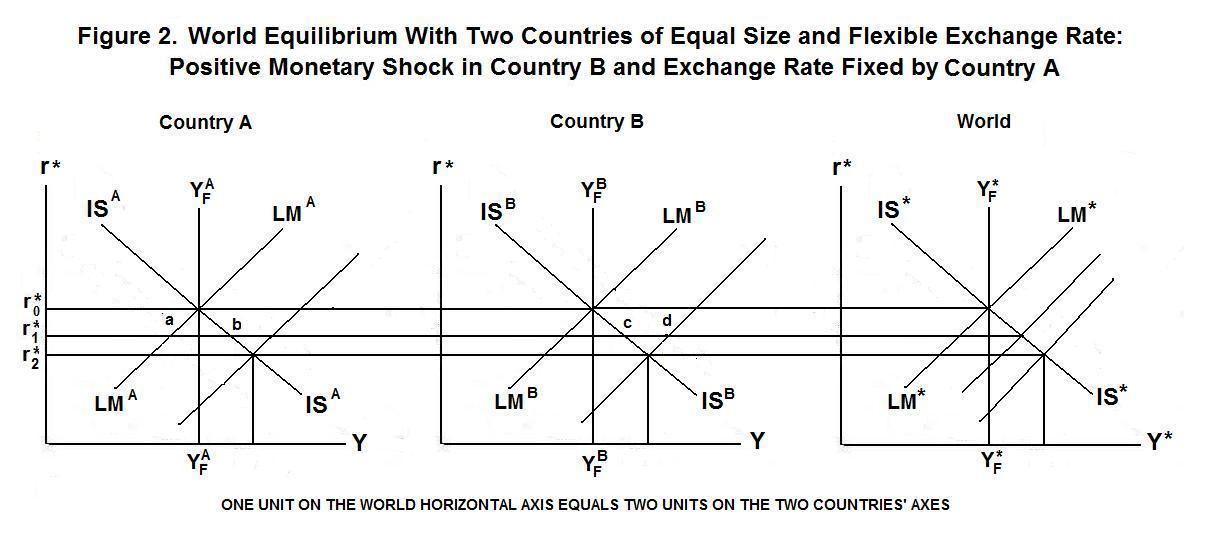

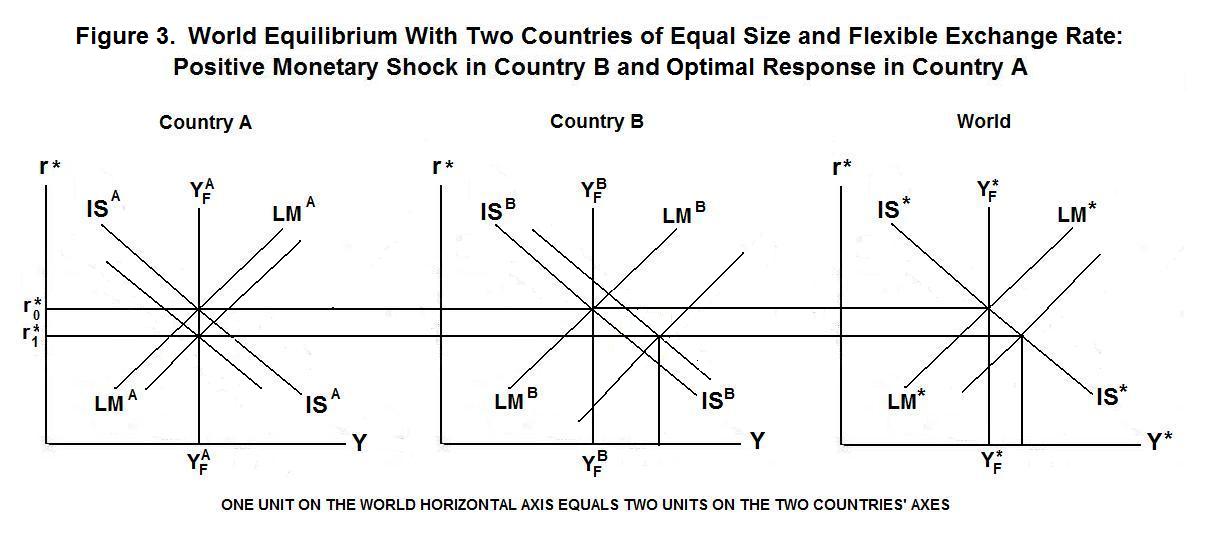

But the Country A aggregate can do better if its authorities have perfect information about the shocks in Country B and the structure of the world economy. They can expand their money supplies to limit the devaluation of B-currency to the point where their IS and LM curves cross the world real interest rate line at full-employment. This causes a shift of Country A's IS and LM curves to the right, and Counry B's IS curve to the left as compared to the situation where the money supply in Country A is held constant. Since the world money supply increases, Country A being half the size of the world, the world LM curve shifts further to the right by half the rightward shift of Country A's LM curve and the world interest rate falls. The new short-run equilibrium is shown in Figure 3.

In the long run the countries composing the aggregate A will have to return their money supplies to pre-shock levels to avoid participating in the inflation that occurs in Country B. That inflation will then be accompanied by a nominal devaluation of B-currency and an increase in Country B's price level in the same proportion as the money shock in Country B, with the real exchange rates returning to pre-shock levels.

In the real world, no monetary authority will deliberately shock a fully-employed economy. The big-country shocks must therefore be viewed as demand for money shocks that the country's authorities had insufficient knowledge to offset or supply shocks whose purpose is to correct previously uncorrected demand for money shocks. And the response of the rest of the world to shocks in the big country shocks will also be constrained by imperfect information. All we can say is that big countries will be able to conduct independent monetary policies but the effects of those policies on the home economy will depend on how the rest of the world responds.

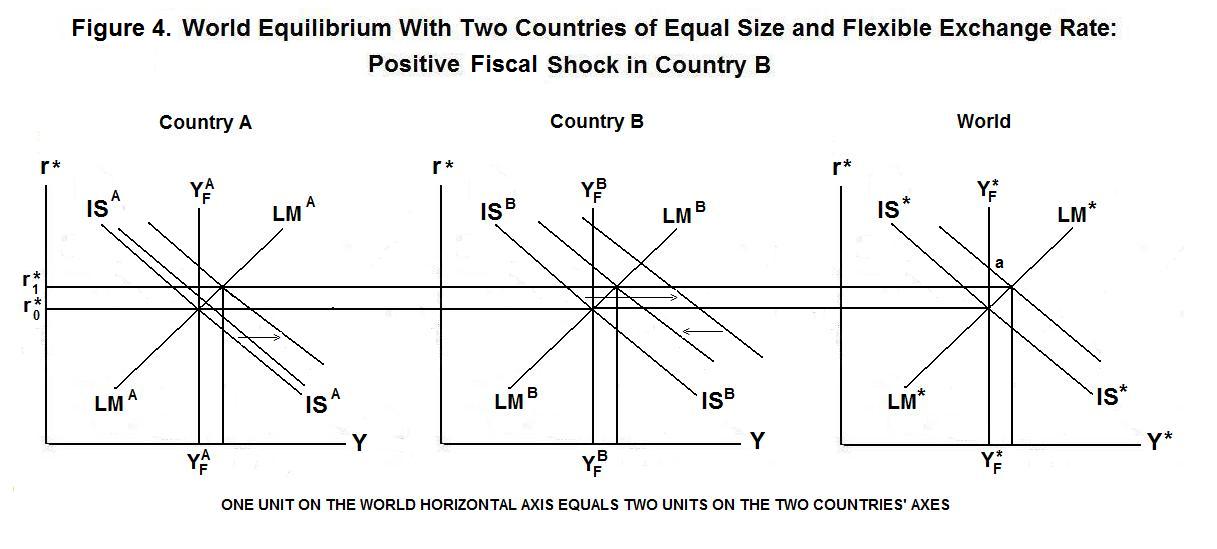

This principle also holds for fiscal policy and exogenous IS-curve shocks in big countries. A positive fiscal or other IS curve shock in Country B, which can also increase Country A's exports and shift its IS a bit to the right, raises the world interest rate to r1* in Figure 4. At that interest rate B-residents have excess demand for money and A-residents excess supply. B-currency will appreciate in both nominal and real terms, shifting ISB to the left and ISA to the right until the portfolio disequilibrium has been eliminated, and there will be a net increase in income and employment in both countries, assuming that the money supplies are held constant.

In the long run, the price level in country B will rise, reducing the world real money stock and increasing the world real interest rate. Country A's price level will also have to rise to force its LM curve through the intersection of the new higher world real interest rate line with its vertical full-employment line. The world real interest rate will ultimately pass through point a. The real exchange rate will adjust to ensure that the IS curves in both parts of the world also pass through the world real interest rate line at full employment. We know that Country B's real exchange rate must end up higher than its pre-shock level because that country's IS curve initially shifted to the right by more than the world IS curve.

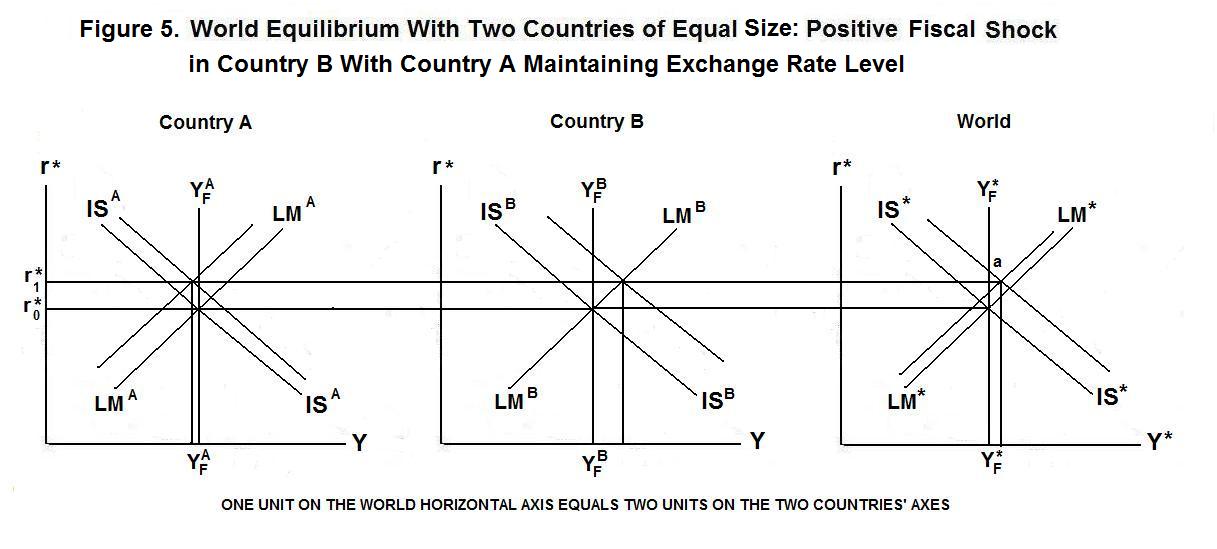

The authorities in the country-A aggregate can prevent the domestic levels of income and employment from increasing in the short run by reducing their money supplies to prevent the currency of Country B from appreciating. If they maintain the exchange rate at its initial level, B-currency becomes in effect a key-currency. Equilibrium occurs at the world real interest rate r1* in Figure 5. In that case Country A's output and employment may either rise or fall in the short-run depending nature of the shock and on the structure of the world economy.

The long-run effect will be inflationary regardless of whether the exchange rate is allowed to float freely. The equilibrium world real interest rate will be the same in both cases---at point a. To prevent these long-run inflationary effects of the Country B shock, Country A's authorities would have to float the exchange rate and make nominal money supply adjustments sufficient to force LMA to cross the world real interest rate line at full employment without a change in the price level. Country B's authorities could prevent an increase in the price level in B by doing the same thing.

The ultimate level of the real exchange rate and, hence, the long-term shift in it as a result of the shock, will be the same regardless of the rest-of-world's reaction to Country B's IS-curve shock. This is the case as long as real exchange rate adjustments do not affect the world IS curve or the levels of full-employment output in either part of the world. Price level increases will occur in any country that does not contract its nominal money supply to match the reduction in the demand for money consequent on the higher world real interest rate.

We can conclude from the above analysis that any big country can operate monetary and fiscal policy to achieve the traditional objectives of those policies regardless of how the other countries respond. The magnitudes of the effects of these policies will depend, however, upon whether other countries hold their money supplies constant and let the exchange rates of their currencies with the big country's currency float, or make changes in their money supplies to offset the effects on their economies of the big country's policies.

Since different countries in the rest of the world may respond differently to different policy shocks and differently to the same policy shocks on different occasions, there is substantial indeterminacy as to the effects of big-country policies on the home economy. And in a world where both real sector and demand for money shocks are frequent, both big and small countries must conduct their policies with considerable attention to how the authorities in the rest of the world are responding. When we take account of the fact that information about the magnitude and direction of these shocks and the response of domestic and foreign economies and foreign authorities to them is poor, and forecasting is an inexact science if it can be called a science at all, it is clear that conducting macroeconomic policy is a difficult task.

It's time for a test. Be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.