Induced transactions are frequent when the exchange rate is fixed---only by

chance will autonomous receipts and payments balance. They can also occur

when the exchange rate is flexible and the authorities want to influence its

movement. But we will concentrate primarily on the fixed exchange rate case

here.

The condition of asset equilibrium---the LM equation---can be presented as the

equality of the demand and supply of nominal money balances as follows:

1. M = mm H

= mm (R + Dsc) = P [ γ −

θ ( r* + τ) + ε Y ]

where Y is real income, P is the price level,

r* is the real interest rate determined by conditions in the

rest of the world, τ is the expected rate of

inflation, mm is the money multiplier, R is the stock

of official foreign exchange reserves, which can be thought of as the foreign

source component of the stock of base money and Dsc is the domestic

source component of the stock of base money H.

The above equation can be manipulated to present the equilibrium stock of high

powered or base money as

2. H = R +

Dsc = (P / mm) [ γ −

θ ( r* + τ) + ε Y ]

which can be further rearranged to move the stock of foreign exchange reserves

R to the left side.

3. R

= (1 / mm) P [ γ −

θ ( r* + τ) + ε Y ]

− Dsc

An increase in the demand for money, given by the P times the

expression in the square brackets [..], leads to an increase in the stock of

official foreign exchange reserves as the authorities act to maintain the

fixed exchange rate. A reduction in the money multiplier increases the stock

of base money required to support the existing quantity of money,

requiring in an increase in the stock of reserves to provide the additional

base money demanded. An increase in Dsc leads to an equal decline

in the stock of foreign exchange reserves as the authorities are forced to

keep the stock of money unchanged at its desired level to maintain the exchange

rate parity.

The authorities are forced to maintain a stock of reserves that will provide

domestic residents with their desired money holdings, given the domestic source

component. This implies that the commercial banks and the public will

have their desired stock of base money. It also means that the authorities

can effectively control the stock of official foreign exchange reserves by

manipulating the domestic source component---such changes in the stock of

reserves can be brought about at no cost in terms of price level changes, or

output and employment changes when the price level is fixed. As you should

have learned in the previous two lessons, output, income and prices are

determined by the conditions of flow equilibrium.

It is evident from Equation 3 above that we must distinguish between two

types of balance of payments disequilibria---stock and flow. A one-shot

adjustment of the domestic source component or shift in the demand for base

money holdings at a moment in time will lead to a shift in the stock of

official reserves at that moment in time. The stock of official reserves

will typically also be growing or declining at some rate through time---it is

this flow of increases or decreases in the stock of reserves that is commonly

referred to as the balance of payments surplus or deficit, which can be

expressed as

4. ΔR

= Δ[(1 / mm) P [ γ

−

θ ( r* + τ) + ε Y ]]

− ΔDsc

where Δ is the change per unit time. Official reserve

holdings change through time because the levels of income, prices, and the

real interest rate and the money multiplier change through time---the effects

of these changes are captured by the major collection of terms in the square

brackets to the right of the equal sign. They also change as a result of a

change in the domestic source component ΔDsc through time.

Notice that the presence of balance of payments equilibrium is completely

independent of the condition of flow equilibrium---indeed, we did not have to

include the IS equation in the above discussion. This is the case as long

as people are free to buy and sell assets in the international market. There

is no relationship of balance of payments equilibrium to equilibrium in the

balance of trade---balance of payments equilibrium is entirely a monetary

phenomenon. All this changes when we assume that there is zero private

international mobility---that private residents are prohibited from purchasing

assets from or selling them to foreign residents. In this case, the only

domestically held foreign assets are official foreign exchange reserves and

the condition of balance of payments equilibrium becomes

ΔR = BT

where BT is the balance of trade---the balance of

payments surplus or deficit becomes equal to the balance of trade surplus

or deficit. To maintain balance of payments equiibrium the government has

to bring about changes in the balance of trade by bringing about changes

in the price level or income and employment or allowing the nominal exchange

rate to change.

When there is international private capital mobility, the government can

control the time-path of foreign exchange reserves simply by controlling the

time-path of Dsc. But shocks to the demand for money are unpredictable

and the main adjustment to these shocks will necessarily be the day-to-day

purchases and sales of foreign exchange reserves in return for domestic

currency necessary to keep the exchange rate at its fixed parity. Changes in

the domestic source component perform the role of providing for long-run growth

in the money supply to match the growth in demand as income and the volume of

transactions rise with time.

Without growth in the domestic source component, the stock

of foreign exchange reserves would grow without limit as the

country's income and demand for money grows. This growth of

reserves must be controlled because short-term foreign government

securities, the main assets held as official reserves, are not a particularly

good form for a country to hold large quantities of its wealth.

Given the country's employed capital stock and the amount

of wealth its residents possess, the bigger the fraction of that

wealth held in the form of short-term foreign assets, the smaller

will be the fraction held in equity and fixed income claims

against domestically employed capital which will yield much higher

returns than the treasury bills that form the greater part of the stock of

official foreign exchange reserves.

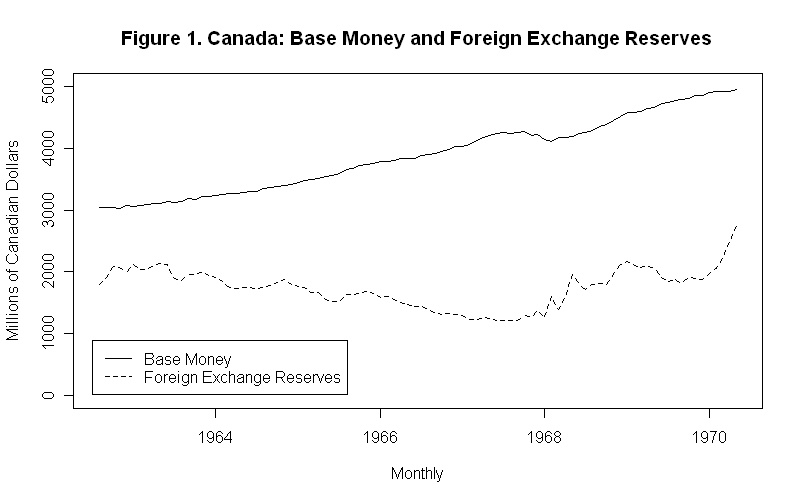

The Canadian period of fixed exchange rates between late-1962 and mid-1970

provides an interesting example of the growth of official reserves in relation

to base money. Figure 1 presents the two series expressed in millions of

Canadian dollars.

Balance of payments equilibrium occurs when induced balance of payments

transactions---those engineered by the government to influence the nominal

exchange rate---are zero. This implies that autonomous receipts from exports

and the sale of securities abroad equal autonomous payments for imports and

the purchase of securities from foreign residents. Since changes in the stock

of official reserves of foreign exchange are the method used by the authorities

to fix or otherwise manipulate the exchange rate, balance of payments

equilibrium requires that the stock of foreign exchange reserves be

constant.

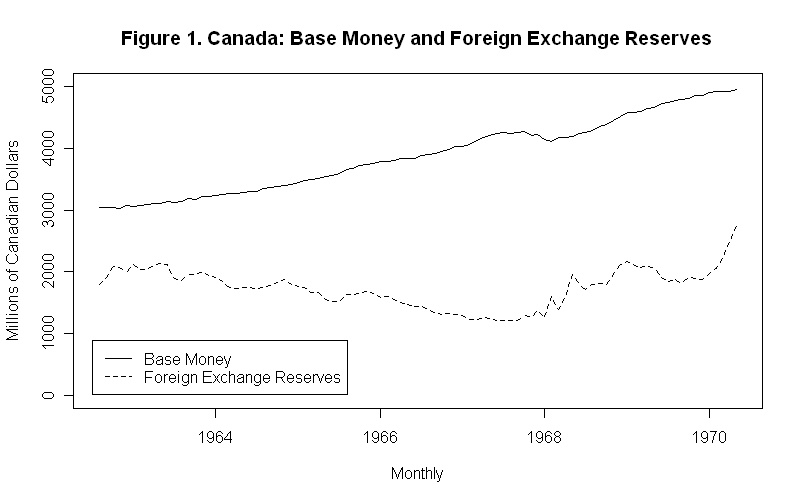

Base money grew steadily in Canada except for a slight dip in late-1967 and early 1968. The Canadian stock of official foreign exchange reserves, on the other hand, declined very gradually until late-1967 and then trended upward thereafter, increasing sharply in 1970. The month-to-month changes in Canadian base money and official foreign exchange reserves are plotted in Figure 2.

The month-to-month changes in official foreign exchange reserves were much more variable than the month to month changes in base money, particularly in 1968, and reserves grew very sharply in early 1970. How do we explain this?

The fact that reserves were more variable than base money suggests that these changes in official reserves were driven in considerable part by changes in the opposite direction in the domestic source component. Since H equals R plus Dsc , greater variability of R than H can only result from variability of Dsc in the opposite directions. An ordinary least squares regression of the month-to-month changes in foreign exchange reserves on the month-to-month changes in base money indicates no statistically significant relationship between them. The slope coefficient is negative with a P-Value of .23 ---indicating a 23 percent chance of observing a negative value of the magnitude observed purely on the basis of random chance when the true value is in fact zero---and the R-Square is only .01.

We have to conclude that much of the variability of the stock of official reserves was the result of the Bank of Canada's manipulation of the domestic source component but we should not venture a conclusion as to why the Bank was doing this without much more careful study. It is well-known that the Canadian Government abandoned the fixed exchange rate in mid-1970 in order to allow the government to control increasing upward domestic inflationary pressure which it was powerless to control under a fixed exchange rate. Accordingly, the observed escalating increases in the stock of official reserves in 1970 may well be the result of a fruitless attempt by the Bank of Canada to get a handle on domestic inflation by reducing the growth of the domestic source component of high-powered money. The only way to get control was to let the Canadian dollar float freely in the international market---only then could monetary policy become effective.

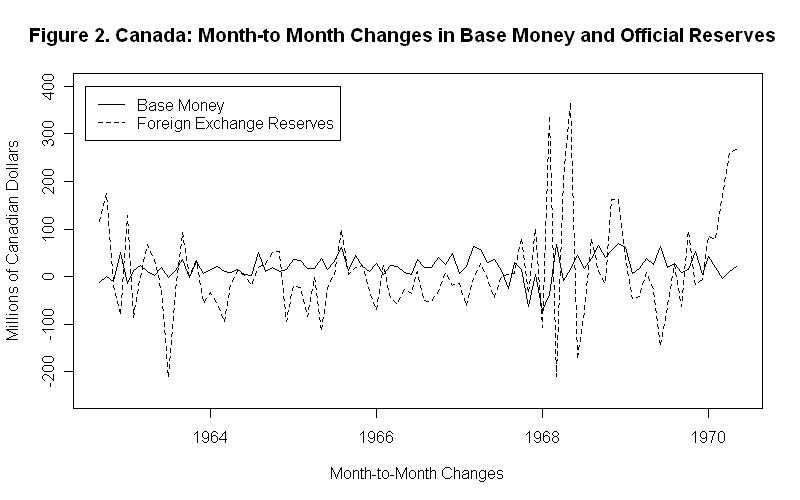

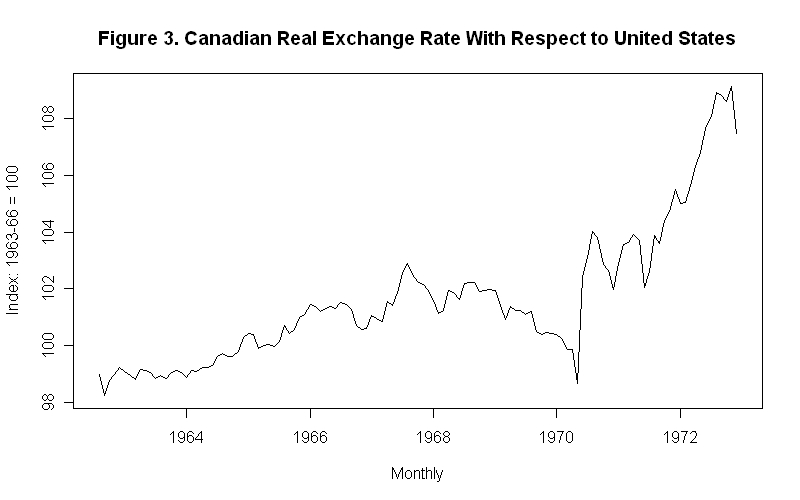

With respect to Canada's abandonment of the fixed exchange rate, it is useful to look at the movements in her real exchange rate with respect to the U.S., plotted in Figure 3.

Recall from the definition of the real exchange rate that

P = Q Π P*.

If the government fixes the nominal exchange rate, the Canadian price level will vary up and down relative to the price level in the U.S. in response to movements in the equilibrium level of the real exchange rate Q arising from shifts in desired exports relative to imports, shifts in domestic relative to U.S. consumption and investment, changes in commodity prices, and so forth. When the exchange rate is fixed the Bank of Canada can not use monetary policy to avoid these price level changes.

Notice from Figure 3 that the real exchange rate increased by about 3.5 percent between mid-1962 and mid-1967---an average rate of of increase of a bit less than 3/4 of a percent per year. Then between mid-1967 and mid-1970 the real exchange rate fell by about the same amount---at an average rate of about 1 percent per year. One would not be surprised if the Bank of Canada tried to offset this decline, particularly the sharp decline in late-1967 and early 1968, by manipulation of the domestic source component. In this respect, you should keep in mind that the basic theoretical framework that we are applying here was not understood at that time, apart from the special case where there was perfect capital mobility, then interpreted as an extreme situation where domestic and foreign assets are identical. The instability of the month-to-month changes in the stock of official foreign exchange reserves during 1968 may have reflected failed attempts by the Bank of Canada to control the stock of base money. Finally, notice the 5 percent increase in the real exchange rate that occurred over June, July and August of 1970. Were the nominal exchange rate held fixed, this would have implied a 5 percent increase in Canada's equilibrium price level over the three month period. It is not surprising that the country abandoned the fixed exchange rate. Indeed, the real exchange rate increased by an additional 5 to 6 percent between late-1970 and late-1972, making the abandonment of the fixed exchange rate a wise decision.

Despite these Canadian hassles, the above discussion of balance of payments disequilibrium seems tame in comparison to what one reads in the popular press. One reads about international currency crises as edgy investors shift funds from currency to currency, creating havoc with the payments system. In fact, most of the time things are very quiet. But occasionally the ability of a country to maintain its fixed exchange rate parity comes into question. Major movements in a country's real exchange rate, as demonstrated for Canada, particularly downward ones that by pressing down on the domestic price level will lead to increased unemployment, are a good reason to expect abandonment of a fixed exchange rate. Another very real possibility is that the government is under political pressure to finance some of its expenditures by printing money---that is, having the central bank buy bonds from the treasury which will use the money so obtained for public expenditure. Or it may be that the government is under pressure to expand the money supply to deal with a difficult domestic unemployment situation in the face of a forthcoming election. Whatever its cause, such monetary expansion is inconsistent with maintaining the nominal exchange rate fixed. It becomes a reasonable bet that the country's currency will devalue in the future.

The spectre of a potential future devaluation presents big expected profit opportunities. If the domestic currency in fact devalues there are enormous gains to having one's assets denominated in foreign currencies while if devaluation does not occur little is lost by holding these currencies. Not surprisingly, huge shifts of funds out of domestic currency denominated and into foreign currency denominated assets occur under these conditions. To maintain the exchange rate in the face of these speculative pressures, the authorities must sell large quantities of foreign exchange reserves. This seems to put them in danger of eventually running out of reserves, in which case devaluation becomes inevitable. As official reserve holdings continue to fall, the pressure mounts. Of course, the country's authorities can easily, and costlessly in terms of effects on employment and prices, avoid running out of reserves---all they have to do is reduce the domestic source component of the money supply, something they may be reluctant to do under less-than-full-employment conditions.

Although governments can borrow official reserves from the governments of other countries in emergency circumstances or, better still, costlessly create them by reducing the domestic source component of base money, they must eventually put their house in order. This means either abandoning the fixed exchange rate, thereby proving the speculators to be right, or establishing credibility in the eyes of asset holders that the domestic money supply will be allowed to be determined endogenously at the fixed exchange rate, regardless of the real exchange rate shocks and public finance demands that may arise.

Speculative pressures on the exchange rate sometimes also arise under flexible exchange rates. When investors think that a currency will depreciate in the future, they will shift funds out of assets denominated in that currency now. This means that the prices of those assets will fall and interest rates on them will rise to reflect a forward discount on the currency expected to depreciate. Under these circumstances, central banks may "lean against" movements in the external value of their currencies by purchasing and selling foreign exchange. Balance of payments disequilibria can thus arise even when the exchange rate is flexible although these are of minor consequence and probably should not even be referred to as disequilibria.

The difference between speculative pressures under flexible and fixed exchange rates is that under flexible exchange rates it is harder to guess which way the rate is likely to move in the future. When speculative pressures arise under fixed exchange rates it is usually quite clear in which direction, if any, the exchange rate will move.

An additional issue should be mentioned before we proceed to the test. It should be obvious that sterilization of the effects of changes in official holdings of foreign exchange reserves on the money supply is impossible under fixed exchange rates when assets can be freely bought and sold across international boundaries. Suppose that the demand for nominal money holdings declines and R falls. Any attempt of the authorities to offset this fall in R by an increase in Dsc will lead to a further fall in R equal to that increase in Dsc. The government has no control over the domestic money supply under fixed exchange rates.

It is time for a test. Figure out your own answers to the questions before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson