There are two general principles that should govern

investment behavior in a world of efficient markets where one

has the same information as other market participants have.

The first principle is the principle of diversification---of

"not putting all one's eggs in one basket". The second is the

principle that one can obtain a higher returns over the very long

run (though not necessarily in the short run) by investing in

riskier assets. To put the second point differently, market

participants require a higher return from an asset, and will

correspondingly pay a lower price for the income stream from it,

the greater the risk. This topic deals with the first of these

principles.

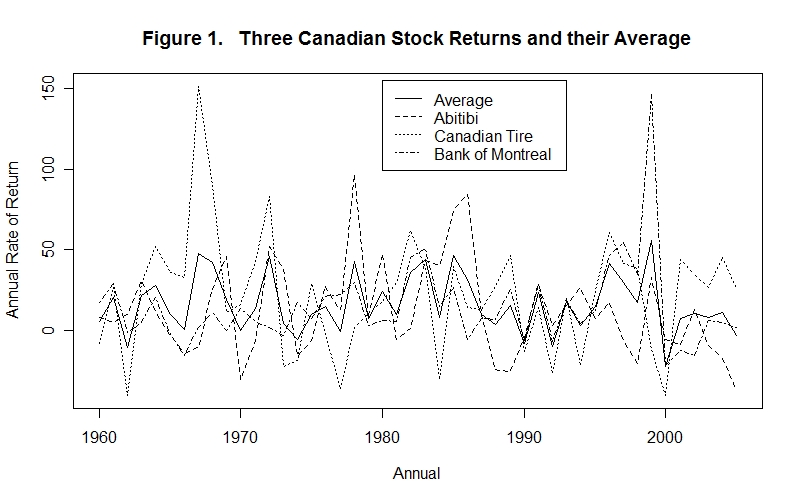

The principle of diversification is illustrated in Figure 1. The dotted or

broken lines show the annual yields (including dividends and capital gains)

of three selected stocks sold on the Toronto Stock Exchange (TSE). The

solid line shows the annual yield of a portfolio containing all three

stocks, each making up one-third of the total. The variability of the

portfolio return is clearly less than the variability of the returns to

the individual stocks that comprise it.

One might get the impression from studying the previous

topic that it makes no difference how one holds one's wealth---asset

prices reflect all existing public information and are consequently

just as likely to go up as down, so one is just as well off holding one

randomly selected asset as another. This is not the case.

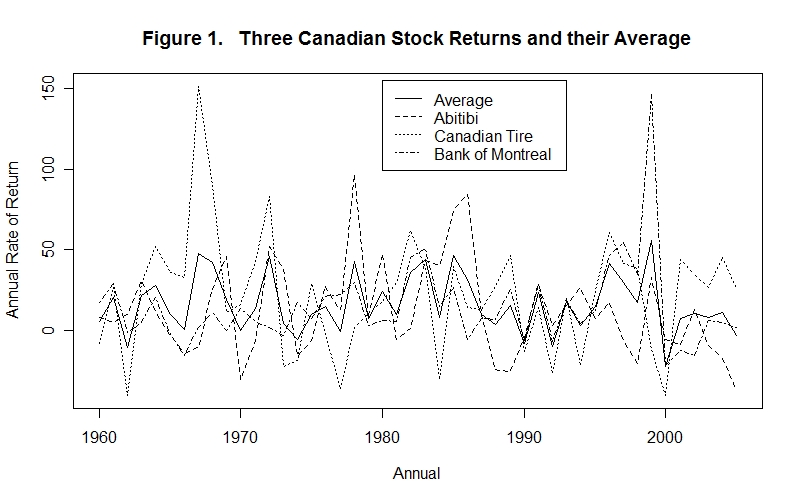

By holding a collection of stocks rather than a single stock one can expect to earn a more stable return because losses on some stocks tend to be averaged out by gains on others. Since variability means risk of potential loss, an investor can reduce risk by diversifying his/her holdings across a wide group of securities. The same three stock returns are plotted against the return to the Toronto Stock Exchange TSX300 index in Figure 2.

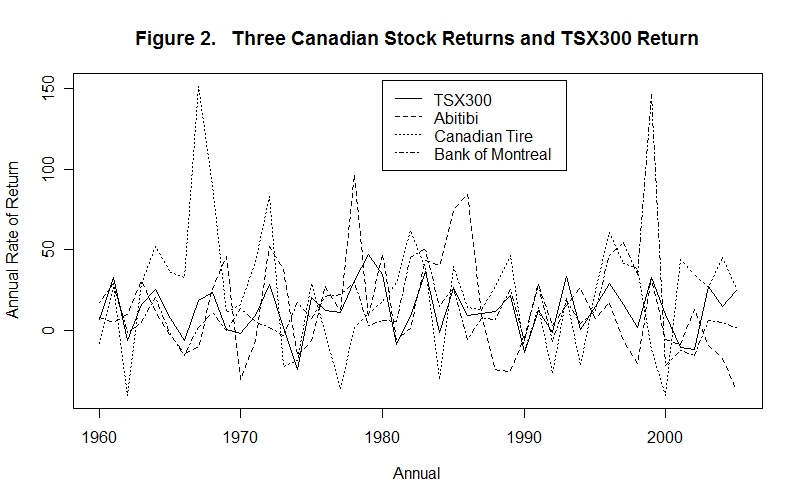

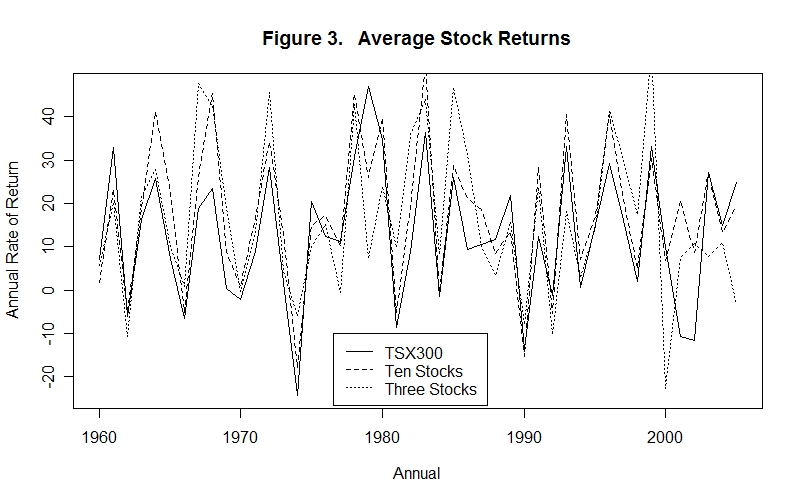

It is not obvious from a comparison of Figures 1 and 2 that the variability of the TSX300 return is less than that of the three-stock portfolio. But it is in fact less variable as can be seen from Figure 3, which plots the return from the TSX300, the return to the three-stock portfolio and, in addition, the return to a ten-stock portfolio that adds an additional seven stocks to the three-stock portfolio.

It is clear from this Figure 3 that the return to the TSX300 index is less variable than that to both the three-stock and ten-stock portfolios with the ten-stock portfolio seemingly doing better than the three-stock portfolio.

To make a clear comparison we need a measure of variability. The variance of a series is the average of the squared deviations of its values from their mean or average level. For any series X having values in N successive periods the variance is

var(X) = [(X1 - mean(X))2 + (X2 - mean(X))2 + (X3 - mean(X))2 + (X4 - mean(X))2 + ................... + (XN - mean(X))2] / N

and the standard deviation of the series is simply the square root of the variance, or the average absolute deviation of the series from its mean.

The standard deviations of the three-stock and ten-stock portfolios, and the TSX300 index are, respectively, 17.98, 16.22 and 15.64 percent of their values. Their mean or average percentage returns per year over the 46 years are, respectively, 16.14, 17.41 and 12.71. The three stocks in the three-stock porfolio had mean returns of 12.21, 21.82 and 14.39 percent with corresponding standard deviations of 29.40, 36.50 and 26.39 percent. It turns out that the ten-stock portfolio produced a return 4.7 percentage points higher than the TSX300 at a cost of less than one additional percentage point of standard deviation! This is an illustration of the superiority of hindsight over foresight---to show that a ten-stock portfolio would have generally been superior to the TSX300 index, one would have to compare the percentage return of the TSX index and its standard deviation with the returns to all possible ten-stock portfolios and the corresponding standard deviations of those returns. Undoubtedly, one would find ten-stock portfolios that were clearly superior to holding the TSX300 index as well as many ten-stock portfolios that were much worse. Indeed, one could easily find a single stock that was superior to the TSX300 index over the past 46 years, but that in no way suggests that, from now on, one should invest one's entire portfolio in that stock! One's investment behavior should depend on what one can reasonably expect to happen, not simply on what could happen!

It should also be noted that the returns to the individual stocks in any selected portfolio may be correlated with each other. These returns represent the earnings of firms that are all operating under the same general economic conditions. When times are good, most firms tend to do well and when times are bad most suffer. The purpose of diversification is to reduce the risk of unforeseen changes in one's wealth. Because the returns to assets tend to be positively (though loosely) correlated with each other, however, the elimination of all variability of the average portfolio return by diversifying across them is impossible. We turn in the next topic to the problem of evaluating and attaching a price to this risk.

Before proceeding, however, we need to have a test. As always, be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson