Competitive pricing is an essential feature of supply and

demand analysis. The supply curve gives the minimum price at

which producers will supply the product---it reflects competition

among sellers in bidding the price at which each output level

will be sold to its minimum level.

We now examine situations where suppliers are able to

collude in setting price. When there are many suppliers, it is

difficult for them to collude because it is profitable for each

individual supplier to break a collusive agreement. Collusive

agreements when there are many suppliers are therefore usually

enforced by the government.

Government could also promote collusive pricing agreements

by ensuring that such agreements are enforceable in the courts.

In fact, however, governments typically do the reverse---most

countries have anti-trust or anti-combines legislation that

makes such agreements illegal. Since this drives collusive

agreements underground, it becomes difficult to maintain them

except in cases where there are a small number of producers.

Here we will consider situations where the government has created

collusive pricing arrangements in order to subsidize producers

in industries that are favored in the political process.

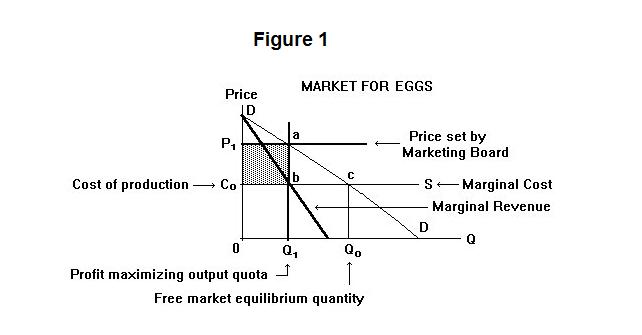

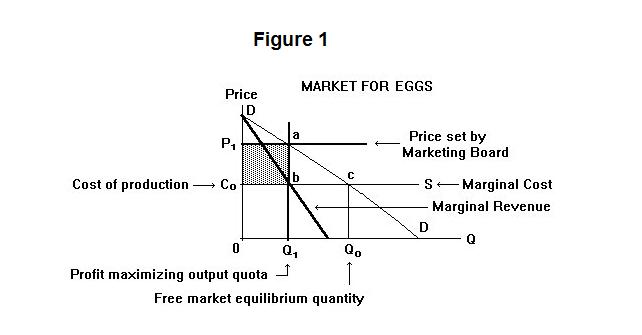

Figure 1 deals with a situation where the government, under

pressure from the farm lobby, creates a government sponsored but

producer run Egg Marketing Board to establish and maintain a

"fair" price for eggs. For simplicity we assume that the supply

curve for eggs is perfectly elastic. The demand curve has a

negative slope because, we assume, the government imposes

regulations ensuring that all eggs consumed in an area are

produced in that area. The "fair" price, set at P1,

will induce an infinite supply from producers, so steps have to be

taken to limit that supply to the quantity demanded at the

price P1.

Anyone attempting to manipulate the price of a product must

understand a basic principle---to control the price it is necessary to

control the supply.

In order to maintain the price at P1, the Board has to limit quantity to Q1. Each existing producer is given a share of the overall quota and is allowed to market only that amount. Producers' cost of production is C0, so they earn a profit per unit over and above their costs equal to the distance a b and a total profit equal to the shaded area. Since the marginal revenue curve crosses the marginal cost curve at output Q1, that output is the profit maximizing output for egg producers. Producers capture from consumers an amount of their surplus or rent equal to the shaded area. The Board's pricing policy thus redistributes income from consumers to producers---which is what the government set it up to do.

The social benefit from additional egg production at the quantity Q1 is the distance between the point a and the horizontal axis. The social cost of an additional unit is the distance between point b and the horizontal axis. A net gain to society equal to the distance a b would occur if the output of eggs were increased by one unit. Indeed, net gains would occur from output expansion until the level of output has reached Q0. At that point the marginal social benefit from expanding output by one unit just equals the marginal cost. The efficiency loss from restricting output to Q1 from its optimal level Q0 is thus the triangular area a c b.

The effect of the Marketing Board's policy is thus to drive a wedge equal to the distance a b between the marginal social benefit from egg consumption and the marginal social cost. The government, by setting up the Egg Marketing Board, has in effect created an externality, the purpose of which is to redistribute income from consumers to egg producers. This redistribution of income carries with it the efficiency loss a c b. In order to redistribute pie from consumers to egg producers, the government has made the pie smaller.

The policy has another interesting implication. Many more farmers will now want to get into egg production---without regulating output, the quantity supplied would in fact become infinite. But the Marketing Board cannot give them output quotas without taking quotas away from some other producer. In order to market eggs, a producer needs a quota. As existing producers retire or leave the industry, they will sell their quota rights to new producers for a price that fully reflects the future stream of profits that will result from the Board's pricing policy. So the producers who are in business at the time the policy is instituted capture all the gains from that policy---new producers have to pay market prices for the right to receive the excess profits when they enter the industry.

One way of ensuring that new producers will also profit from the egg marketing policy is to prohibit the sale of quota rights. Producers can be forced to give up their quota rights when they retire and the Marketing Board can be empowered to reallocate these quotas to new producers. This then raises the question of which potential new producers are to receive quota rights---the number of potential entrants is extremely large and the aggregate output quota must be maintained at Q1. If price can not be used as a mechanism for allocating quotas, some other mechanism must be created. Should new quotas be given to sons of existing quota holders' (or their daughters!)? Or to those young people whose can trace their ancestry in farming back the farthest? Or to those who can demonstrate that they are the most public-spirited. Or to sons and daughters of the Marketing Board members or local politicians? One of the problems of not using prices as the allocation mechanism is that rent seeking is then encouraged. People will use up resources that could produce useful goods fighting over the allocation of rents.

One might wonder why the government would pass laws to prohibit collusion among suppliers and then pass additional laws to enforce collusion in specific favored industries. The reason would seem to be that voters are more concerned with distribution than efficiency. Egg producers are "little guys" who "deserve a break" while large multinational corporations are "big guys" who must be kept from unconscionably exploiting society.

Rather than setting up marketing boards, it would seem more sensible to give producers a straight income payment (to simply write them cheques) and avoid the efficiency losses from interfering in the pricing process. But this is never done, probably because it destroys the illusion that producers are "earning" their keep rather than accepting hand-outs. Straight income payments also draw attention to the fact that producers are receiving a subsidy where as quota-induced price increases can be defended, albeit inappropriately, as providing a "fair" return to producers for their efforts. The legitimacy of various types of subsidy involves complex political issues central to the problem of public policy design.

It is test time. As always, be sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.