Let us start with a big country like the United States. Given the time

required to collect and organize data, the actual levels of output and prices

can only be determined with appropriate accuracy a month or two after they have

occurred. Only with such a lag can the authorities determine how far output is

below or above its full-employment level, which itself is difficult to

estimate, and whether prices seem to be rising faster or slower than desirable.

And the upward or downward adjustment of nominal liquidity, of which M1 and M2

represent alternative measures, resulting from a deliberate expansion or

contraction of the monetary base will depend on how the respective money

multipliers subsequently change. Furthermore, time will pass before the

resulting monetary expansion or contraction impacts the levels of output and

employment and subsequently prices. What really matters is not the present the

state of the economy but the state it would otherwise be in when the monetary

policy actually has its impact. If full employment would have otherwise been

achieved by that time without the monetary policy adopted, the effect of that

policy will be to drive the economy away from long-run equilibrium in the

opposite direction to its present disequilibrium state.

Such complications arise from the fact that the original deviation of

output from its full-employment level has resulted from the inability of private

decision makers to correctly estimate the levels at which they should have set

wages and prices. Getting back to full-employment without monetary policy

adjustments will depend on how fast these individuals learn about the correct

settings. If the private sector and the central bank have the same information

about the current state of the economy, and learn equally well as new

information emerges, the actions of private decision makers may well have driven

the economy back to full-employment equlibrium by the time the central bank

actions actually take effect. Central bank countercyclical policy actions will

then add to rather than reduce the variability of output around its

full-employment level. To the extent that the central bank has more information

about the long-run equilibrium state of the economy than the private decision

makers who would get it there, it should simply publish that information. This

conclusion depends, of course, on the assumption that the private sector is not

locked into disequilibrium wage and price settings by past contracts. While

there will undoubtedly be some sectors that are constrained in this fashion, it

is difficult to imagine how this could be the case for an entire economy like

that of the United States.

Even if the central bank decides to forego such attempts to offset

counter-cyclical shocks to the economy it still faces the problem of

maintaining a stable and low long-run inflation rate. To do so it must produce

a rate of liquidity growth that varies only in response to changes in the

trends of long-run full-employment output and demand-for-liquidity growth. But

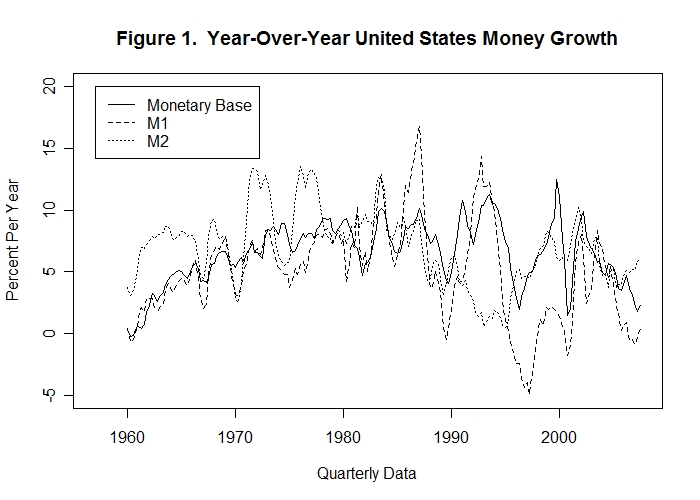

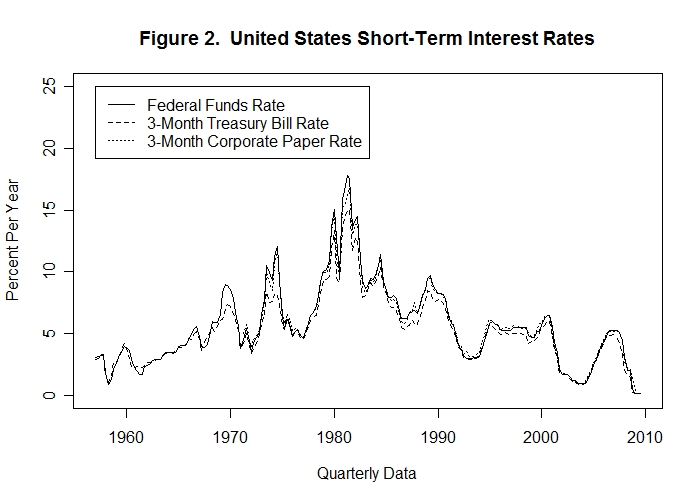

how is liquidity growth to be measured? Figure 1 plots the year-over-year rates

of growth of United States base money, M1 and M2 quarterly for the period

1960 through 2007.

We close this series of computer-assisted learning modules with an analysis of

issues relating to the actual conduct of monetary policy by central banks, using

directly or indirectly, all of the ideas developed in the previous seven modules.

Central to our discussion will be the fact that those responsible for making

day-to-day decisions about what their central bank will do may fully

understand and agree with the basic model underlying our analysis but,

like everyone else, know the signs but not the actual magnitudes of the

underlying parameters. Moreover, while the analytical structure we are

using tells us about the short-run and long-run implications of various

exogenous shocks and policy actions, it gives no indication of the time-path

of adjustment. While relevant dynamic models can be constructed, the results

will depend on the exact structure of each particular model---everything

depends on how quickly people making decisions in the economy learn about

the exogenous shocks and policy responses that occur.

Clearly, the observed growth rates of the M1 and M2 money stock measures do not always move in the same direction, nor in the same direction as the growth rate of base money. To maintain a stable long-run rate of liquidity growth, which measure of the money stock should the Federal Reserve Bank attempt to stabilize? And if it were to successfully stabilize one of these money supply measures, what would be the consequences? These questions have no clear answers!

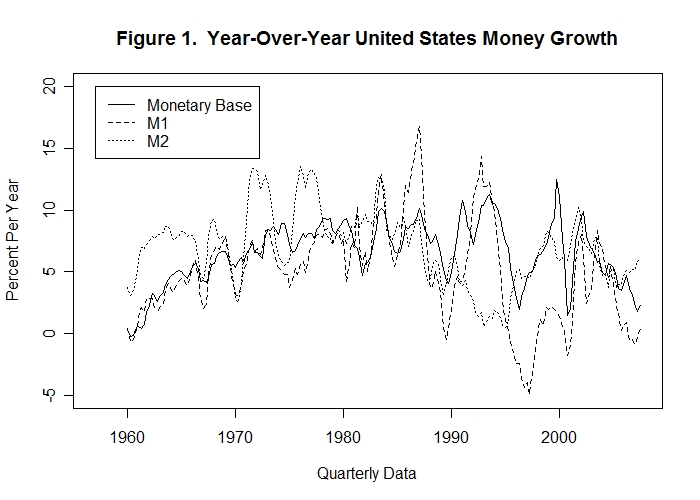

Rather than attempt to manipulate selected monetary aggregates directly, the emphasis in the United States and most other countries has been on the manipulation of domestic interest rates. The idea is to adjust the stock of base money so as maintain underlying real interest rates at their full-employment levels---in contrast to the single real interest rate in our models, there will be many real interest rates in the economy that differ from each other by the underlying risk premiums.

The real interest rate that the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank attempts to control is the federal funds rate, which is the rate at which the commercial banks borrow from and lend to each other, on a short-term basis, reserves deposited with the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee sets a target range for this market rate at its regularly held meetings. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York then engages in open market operations that attempt to move the federal funds rate in the desired direction. It is widely believed that the Federal Reserve System, by changing the stock of liquidity in the economy, thereby manipulates not only the federal funds rate but the basic level of interest rates throughout the United States. Figure 2 presents the federal funds rate, the 3-month treasury bill rate and the 3-month commercial paper rate in the United States from 1960 to the present.

One is struck by the high degree of correlation among the three interest rates as well as their very substantial variability, and the problem of using control over interest rates as the basis of monetary policy becomes immediately evident. The authorities observe only nominal interest rates, not the real interest rates that they need to continually force to their full-employment levels. It is quite clear that the monetary authorities can control nominal interest rates since their monetary policy is exclusively responsible for the domestic inflation rate, the expected magntude of which adds to real interest rates to produce the nominal ones. There is clearly no evidence of control by the Federal Reserve System of the levels of real interest rates in the United States. These real rates, while unobservable, would clearly not have followed the observed pattern of nominal rates, particularly in view of the fact that the U.S. inflation rate was high in the 1970s and 1980s when observed nominal interest rates were high.

Further problems arise because the United States, while large compared with most countries, is still only a modest fraction of the industrialized world. Any significant effect of U.S. monetary policy on domestic real interest rates will lead to equivalent effects on interest rates abroad. Moreover, monetary expansion in the Eurozone, to the extent that it successfully affects European real interest rates will affect U.S. real interest rates as well since capital markets are world wide. Also, monetary expansion in any major area of the world will devalue the exchange rates of that area's currency with respect to the currencies of other countries. And as was shown in the computer-assisted learing module, Additional Policy Issues, there is good reason to believe that such exchange rate changes resulting from monetary shocks will tend to overshoot their long-run equilibria in the short run. If other countries care about their exchange rates with respect to the U.S. dollar or the euro, they will tend to adjust their own money supplies to moderate such exchange rate changes. This will augment the expansionary effects of monetary expansion in the U.S. and Eurozone. As a result, big countries' projections of the expected effects of domestic monetary expansion and contraction will depend upon the reaction of the monetary authorities abroad. Even if the rest of the world consists entirely of tiny countries, the aggregate effects of their response to domestic monetary policy may be substantial. Then there is the problem of co-ordination between the U.S. Federal Reserve System and the European Central Bank---should they try to push real interest rates in the opposite directions, or to significantly different extents in the same direction, the dollar/euro exchange rate could go out of sight!

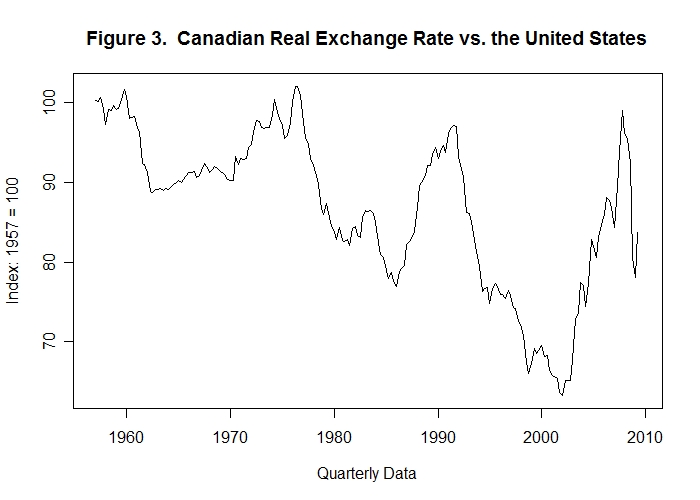

Now let us consider the situation faced by the central banks of small open economies. Their first problem is to correctly forecast what is going to happen in the economies comprising the rest of the world, particularly those of large neighboring countries as in the case of Canada with respect to the United States. One policy option is to fix the domestic exchange rate to the currency of the big neighbor and thereby to free ride off that country's monetary policy. Apart from the loss of control over domestic inflation and variations of real economic activity in the domestic economy that are substantially independent of conditions abroad, a major problem will arise as a result of variations in the domestic real exchange rate with respect to the chosen key-currency neighbor. Variations in the relative price of domestic output in terms of foreign output---that is, in the real exchange rate---require equivalent variations in either the nominal exchange rate or the domestic price level. As an example of this problem, Figure 3 plots the real exchange rate of Canada with respect to the United States from 1960 to the present.

Had Canada permanently fixed the Canadian dollar to the U.S. dollar in 1957, the equilibrium Canadian price level would have fallen relative to the U.S. price level by about 10 percent by 1962, recovered that 10 percent by the late 1970s, then fallen by about 20 percent by the mid-1980s, then risen by almost 20 percent by the early 1990s, then fallen by more than 30 percent by 2002, then risen by about 50 percent of its 2002 level by the end of 2007 and then fallen by 20 percent by the end of 2008. Of course, the actual price level would have moved by smaller amounts than the real exchange rate because the effects of the underlying aggregate demand changes would have been born in large part by the level of Canadian output and employment. So much for fixing the exchange rate!

With exchange rate flexibility, the argument for a constant rate of domestic liquidity growth is much weaker than in the case of the United States. In addition to the problems of measuring liquidity, there is the fact that the demand for liquidity was most likely much more variable in Canada than in the United States because the demand for liquidity in the U.S. represents a pooling of the demands for liquidity over a much larger area. Indeed, during the period between the fourth quarter of 1962 and the first quarter of 1970, when Canada actually fixed her exchange rate with respect to the U.S. dollar, and the Bank of Canada was thereby forced to supply whatever quantities of the monetary aggregates money holders demanded, the standard deviations of the quarter-to-quarter percentage changes Canadian base money, M1 and M2 were more than 3, 8 and 10 times the standard deviations of the quarter-to-quarter percentage changes in the corresponding U.S. aggregates. And the quarter-to-quarter percentage changes in the corresponding Canadian and U.S. aggregates were not significantly correlated with each other. Any attempt by the Bank of Canada to produce a constant rate of money growth, somehow defined, would undoubtedly result in substantial short-term overshooting movements in the Canada/U.S. nominal exchange rate and corresponding short-run movements in the real exchange rate.

The alternative of manipulating domestic real interest rates is also not available to small countries. Given the world capital market, the levels of real interest rates will differ across countries only as a result of risk premiums and expectatons about future movements in real exchange rates. Risk premiums on real capital holdings are not likely to be affected significantly by the monetary policies of stable industrial countries and the best predictor of next period's real exchange rate is, under normal circumstances, its current level. Apart from the United States and the Eurozone, normal domestic money stock changes will by themselves have a trivial effect on the world stock of liquidity. So, given the tendency of domestic money shocks to produce overshooting effects on the domestic nominal exchange rate, what can a small country like Canada do?

Small countries can, of course, change the levels of their domestic nominal interest rates by managing the money stock so as to produce changes in actual and expected inflation rates. But money stock changes cannot produce significant changes in the underlying real interest rates that affect the level of domestic investment. The only avenue through which domestic money supply changes can affect domestic output and employment is their effects on nominal and real exchange rates and resulting changes in the domestic real trade account balance. To avoid overshooting exchange rate effects, the authorities must focus on the manipulation of exchange rates and not directly on changes in monetary aggregates. And, of course, the problem that arises is that as soon as the authorities begin to control the nominal exchange rate they lose sight of its underlying equilibrium value---this is particularly the case because of the major movements likely to occur, regardless of monetary policy, in long-run equilibrium real exchange rates.

Given that on-going demand for liquidity shocks are likely to produce overshooting changes in nominal exchange rates, the authorities have an incentive to smooth out these shocks with appropriate offsetting changes in the supply of liquidity by adjusting the stock of base money---that is to maintain an orderly foreign exchange market. As a result, since inflationary expectations lead to appropriate growth of the demand for liquidity, this policy will tend to automatically finance existing inflationary expectations. This gives the authorities cause to attempt to influence those expectations by announcing their policy intentions. A common way to do this is to announce and appropriately change from time to time the interest rates at which they will loan reserves or take deposits from domestic commercial banks, even though changes in such rates and resulting changes in bank reserves will have no effects on the real interest rates relevant for domestic investment. Intended monetary expansion is announced by lowering those target interest rates and monetary contraction is signaled by raising them. Resulting changes in market expectations may ease the authorities' ability to appropriately change the rate of growth of liquidity without incurring undesired overshooting of resulting exchange rate changes.

To the extent that a small country's authorities can offset exogenous nominal shocks to exchange rates that would cause overshooting while financing an appropriate existing set of market expectations as to the on-going inflation rate, they will produce a domestic monetary policy roughly equivalent to that generated in the countries they trade with while at the same time allowing the underlying equilibrium real exchange rates with those countries to adjust in response to international real shocks without putting pressure on domestic prices and employment. To this extent they achieve some of the benefits of fixed exchange rates without incurring the costs.

Having established that there is no doubt that conducting monetary policy is an extremely difficult business, it's time for a test. With respect to these questions, think deeply and extensively and come up with your own interpretation before looking at my answers.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.