You should by now understand that the aggregate demand for

goods consists of total expenditures for consumption, investment

and net exports. These expenditures are made both directly by

individuals and indirectly through the medium of government---the

government taxes the private sector and uses the funds to

purchase consumption and investment goods to be provided free-of-charge

to private individuals.

In previous lessons we developed the aggregate income-expenditure equation

1. Y

= C + I + BT + DSB

where Y is income, C is aggregate public plus

private consumption, I is aggregate public plus private

investment BT is the balance of trade and DSB is

the debt service balance. Y is total expenditure (or income

generated by domestically owned resources) and the terms to the right of the

equality are the components of that expenditure.

The two components of aggregate expenditure relevant to our

discussion here---consumption and investment---were determined as

follows:

2. C

= a + (1 - s) Y

3. I

= δ + μ r*

where s is the marginal propensity to save ( (1 - s) is the marginal

propensity to consume) and μ is negative.

The lower the domestic interest rate determined by world market conditions,

the more that is spent by the private sector and government on investment.

The higher the level of aggregate income, the more that is spent on

consumption.

When the government provides more consumption goods to the

community at each level of aggregate income, a increases in

Equation 2. When it makes more investment expenditure at each

level of the world interest rate, δ increases in Equation 3.

Simple standard Keynesian analysis postulates that private

expenditures on consumption depend on individuals' disposable or

after-tax income. To the extent, then, that the government

reduces taxes it leaves additional funds in private hands for

expenditure on consumption. Consumption will increase at each

level of aggregate (tax inclusive) income, as a result of an increase

in a .

Equations 1, 2 and 3 together with the equation determining the balance of

trade, combine to yield the real goods market equation with which you should

already be familiar,

1. Y

= ( a + δ

+ ΦBT + DSB)/(s + m)

− μ/(s + m) r*

+ m*/(s + m) Y*

− σ/(s + m) Q ,

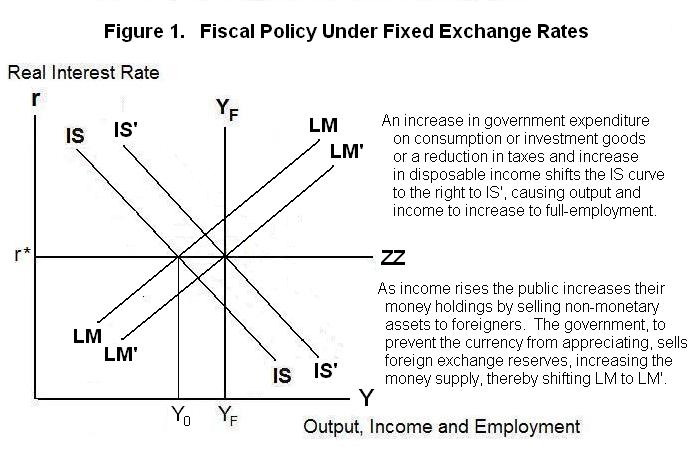

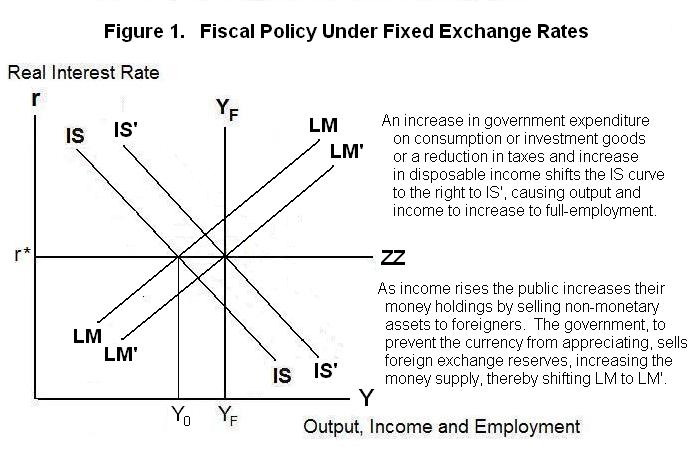

that appears as the IS curve in Figure 1. As can be seen from the equation, an

increase in a or δ will increase Y

at every level of r* , shifting IS to the right. The government

can thus shift the IS curve to the right in Figure 1 by increasing its

expenditure on consumption or investment goods or by cutting taxes to increase

private disposable income, thereby inducing private individuals to increase

their consumption expenditures.

The use of fiscal policy---changes in taxes and government

expenditures---as a method of smoothing out fluctuations in output

and employment came into prominence with the work of John Maynard

Keynes (1883-1946) in the 1930s. The idea behind it is simple---by

changing its contribution to aggregate consumption and investment

expenditure, and adjusting taxes to change the net-of-tax

incomes of private individuals, the government can affect the

aggregate demand for goods.

Consider first the case where the nominal exchange rate is fixed. You should already understand that in this case equilibrium is determined by the intersection of the IS curve and the ZZ line and that the money supply adjusts endogenously (as a result of the government fixing the exchange rate) to drive the LM curve through this IS-ZZ intersection. A fiscal policy that shifts IS to the right will therefore lead, under short-run conditions where the price level cannot change, to an increase in output and employment and an accommodating expansion of the nominal money supply as the authorities provide the public's desired increase in money holdings by adding the the stock of foreign exchange reserves and shifting LM to the right by the same amount as the shift in IS. This is shown in Figure 1 where a fiscal expansion shifts income from Y0 to YF.

When there is price flexibility and full employment, rightward pressure on the IS curve will be neutralized with a rise in the domestic price level in response to the pressure on aggregate demand, assuming that the nominal exchange rate is fixed. As a result, the equilibrium level of prices will be such that the IS curve passes through the ZZ line at the full-employment level of output and income. The LM curve will again accommodate through endogenous money supply changes. It turns out that neither the IS or the LM curve will change in the long run---the price level and real exchange rate will rise to shift the IS curve back to its original position and the LM curve will remain at its initial level because the price level and the nominal money stock will rise in the same proportion, with the money stock increasing as a result of the government's accumulation of of foreign exchange reserves so that the real money stock ultimately remains unchanged.

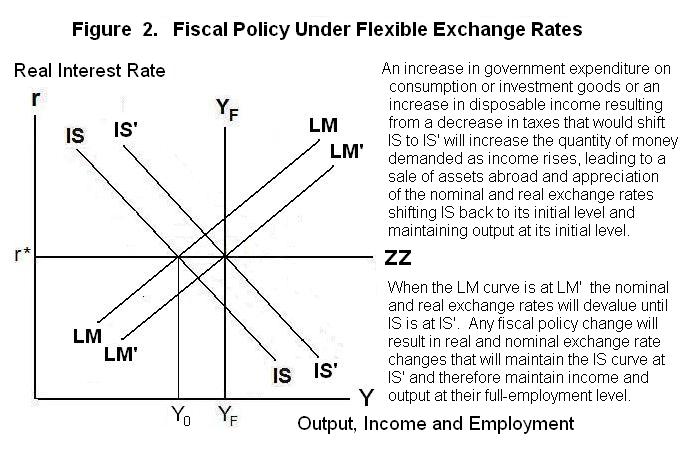

Suppose now that the nominal exchange rate is allowed to fluctuate in response to market forces. Equilibrium is then determined by the intersection of LM and ZZ in the less-than-full employment case shown in Figure 2. The nominal exchange rate adjusts endogenously to ensure that the IS curve passes through the LM-ZZ intersection. In the long-run under price flexibility and full-employment, the only thing that changes is the initial level of output which, as a result of previous adjustments of the real and nominal exchange rates, will now be at YF in Figure 2. Fiscal policy has no effect on either output and employment or prices when the exchange rate is flexible---any attempt to shift IS to the right of IS' will be neutralized by a rise in the nominal and real exchange rates.

An expansionary fiscal policy that shifts IS to the right will put upward pressure on aggregate demand. Any increase in output or prices will lead to an excess demand for money which will result in an attempted sale of assets by domestic residents to foreigners to replenish money holdings. This will cause the domestic currency to appreciate and the real exchange rate to rise, eliminating the pressure on aggregate demand and returning IS to its initial level. A decline in the current account balance will exactly offset the increased government induced expenditure on consumption or investment goods.

Fiscal policy can smooth output and employment and price level fluctuations under fixed exchange rates but is impotent under flexible exchange rates. By contrast, as you learned from the previous two lessons, monetary policy works under flexible exchange rates but not under fixed exchange rates. These basic results constitute what has been named the Fleming-Mundell Theorem after economists Robert A. Mundell (1931- ) and J. Marcus Fleming (1911-76).

It is time for a test. As always, figure out your own answers to the questions before looking at the ones provided.

Question 1

Question 2

Question 3

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson