The capital stock is very broadly defined to include not

only tangible things like trucks, machinery and buildings, but

the skills of lawyers, accountants and truck drivers as well. All

labour input except pure physical activity and time spent is

included in the capital stock---what is conventionally viewed as

labour is simply the hourly application of embodied human capital

in the same sense that the application of physical capital to

production is the hourly use of buildings and machines.

More broadly, the capital stock also includes knowledge of

how the physical and social world works and what types of machines

and human skills can be used to manipulate it. To be part of the

capital stock, this knowledge merely has to be possessed by or immediately

accessible to someone in the economy, not widely embodied in individuals.

Knowledge of how to properly lay bricks, for example, is one part of the

stock of capital---the bricklaying skills embodied in a large number of

bricklayers is an additional and separate part.

The capital stock also includes the institutional and legal

structure that governs the relationships between individuals and

groups engaging in economic activity. These institutions are

part of the capital stock to the extent their organizational forms

and principles are understood by some individuals and, where

relevant, legislated. To the extent that the functioning of

institutions requires that they be widely understood, this understanding

is part of the human capital stock---the skills of lawyers,

judges, clerics, public regulators, and the beliefs and customs

and behaviour patterns embodied in virtually the whole population.

It should be obvious that precise measurement of the various

types of capital is impossible. A common unit in which to measure

the physical quantities of all types of capital is unavailable.

How many units of capital does a particular hairdresser hold as

compared to a truck driver, or a lawyer, or a medical doctor?

It is tempting to try to measure the quantities of capital in

terms of dollars or other currency units. This would equate the

quantity of a piece of capital with its present value which depends,

as we saw in the Lesson Interest Rates and Asset Values,

on the rate of interest used to discount the future earnings stream from

the asset. But by using the interest rate to calculate the quantity of

capital, we foreclose the opportunity to use the quantity

of capital in devising a theory of interest rate determination.

Interest rate changes resulting from a change in the quantity of

capital would cause that quantity of capital to change---application

of our theory shifts its foundations.

We proceed with a purely conceptual measure of the quantity

of capital. By doing so we give up any possibility of addressing

questions whose analysis depends on the units in which capital is

measured. But we can still define observable relationships, such

as the relationship between interest rates and investment, that

will hold independently of the units in which capital is measured.

We define a unit of each type of capital good, whether human,

physical, knowledge, or institutional, as the amount that can be

obtained by giving up one unit of consumption. It is thus assumed

that society can substitute in production all capital goods for

each other or for consumer goods on a one-to-one basis. Total

output is then simply the sum of the quantities produced of an

aggregate consumer good and all capital goods.

The aggregate output produced in the economy thus depends

upon the stocks of all types of capital. Income will equal that

output minus the quantity that has to be set aside and invested in

the various types of capital to compensate for their depreciation.

Ignoring depreciation (an assumption which simplifies our analysis

but does not affect the results) we can express income (= output)

as a function of the stocks of the various types of capital:

1.

Y = F ( K1, K2,

K3,......, Kn )

where Y is aggregate income and K i is

the quantity of the i th type of capital where

i = 1, 2, 3, 4,... n.

A mathematical function such as the production function

F ( K1, K2,

K3,......, Kn )

gives the level of a dependent variable (in this case Y )

associated with each possible combination of the independent variables

( K1, K2,

K3,......, Kn ).

In the case of production functions, we assume that an

increase in the stock of any of the capital inputs will result in

an increase in aggregate output. More formally, the increase in

output associated with a one unit increase in the stock of any type

of capital K i , called the

marginal product of K i , is

positive---that is,

2.

MPKi =

∂Y / ∂ K i > 0

where the symbol ∂ here denotes

a small change in the variable that follows, holding all the

remaining Ki constant. We also assume that

the principle of diminishing returns holds---that is, that an

increase in the quantity of the i th type

of capital relative to the j th type causes

the marginal product of the expanding type of

capital ( MPKi ) to fall and the marginal

product of the contracting type of

capital ( MPKi ) to rise.

3.

∂MPKi / ∂(Ki / Kj)

< 0

4.

∂MPKj / ∂(Ki / Kj)

> 0

Given that one unit of each type of capital can be produced

by giving up one unit of consumption, and given the principle of

diminishing returns, the most efficient division of the aggregate

capital stock into the various types is the one for which the

marginal products of all types of capital are equal.

To see this, suppose that the marginal product of capital of

type i is higher than the marginal product of capital of

type j . Then the amount of output given up by reducing the

stock of capital of type j by one unit is less than the amount

of output that can be obtained by increasing the stock of capital of

type i by one unit. The total output from the aggregate capital

stock will thus increase if we accumulate one more unit of capital of

type i and one less unit of capital of type j . As

capital is shifted from type j to type i the marginal

product of the i th type of capital will fall and

the marginal product of the j th type will rise

(as implied by the principle of diminishing returns), driving the marginal

products to equality. At that point, output will be the maximum possible.

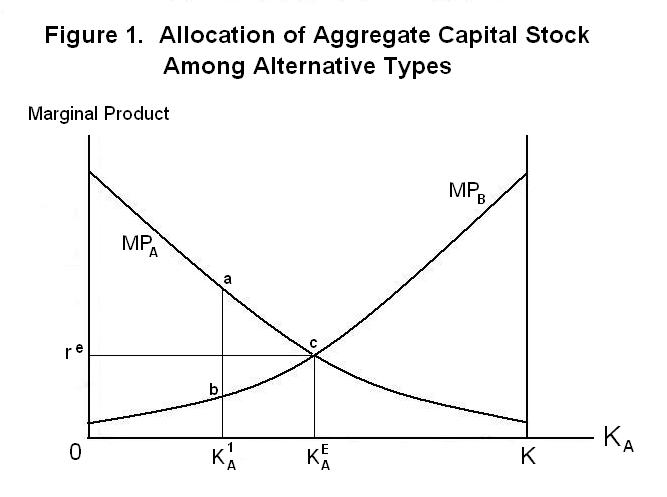

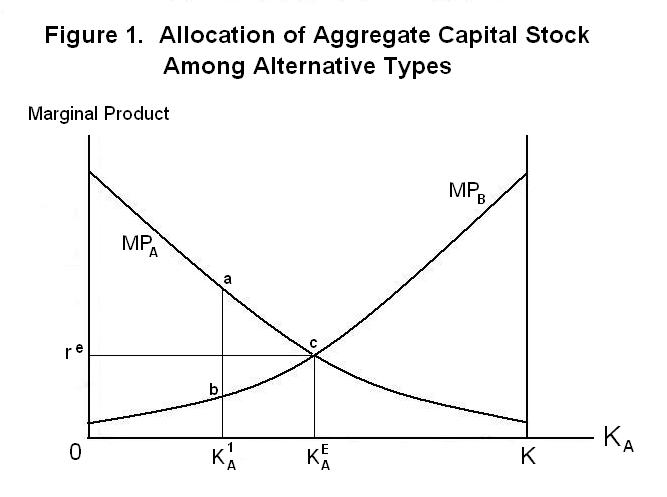

This is shown in Figure 1, which simplifies by assuming that output is produced

with only two types of capital. The lines MPA

and MPB trace out the marginal products of

type A capital and type B capital as the quantity of

A-capital goes from zero to K ,

where

K = KA +

KB .

As KA rises, and KB falls equivalently,

the marginal product of A-capital falls and the marginal product of B-capital

rises. At a quantity of A-capital equal

to KA1 the gain from shifting a unit of

capital from type A to type B will be the

distance a b ---the gain in output from having one more

unit of A-capital, given by the

distance a KA1, minus the loss from having

one less unit of B-capital, given by the

distance b KA1. Output

will be maximized when the quantity of capital of

type A is KAE and the quantity

of type B is then equal

to K - KAE.

In the first Lesson, called The Dimensions of Economic Activity

, we noted that aggregate output in the economy is the flow of

returns from the economy's stock of capital. And income is the

portion of that output left after a sufficient amount has been

set aside to cover depreciation and maintain the capital stock

intact. Analysis of economic growth---the process by which output

and income grow through time---involves an elaboration of these

ideas to consider growth of the capital stock along with changes

in the efficiency with which it produces output. It also involves

a consideration of what determines population growth because per

capita income is aggregate income divided by the number of people.

The rate of interest in the oversimplified economy, denoted by re in Figure 1, is equal to the common marginal product of the two types of capital where the two curves cross at point c . It is the additional output that can be obtained in every future period by giving up one unit of consumption today and adding to to the aggregate stock of capital one unit appropriately divided between capital types A and B .

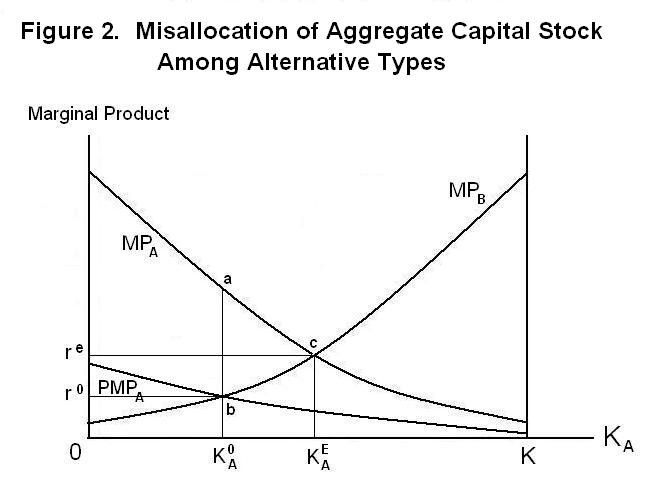

The condition of maximum efficiency, where the marginal products of all types of capital are the same, will most certainly never be met in the real world. The main problem is that the returns to some types of capital, chiefly knowledge and technology, can rarely be completely captured by their inventors, although the use of system of copyrights can go a substantial way toward dealing with this difficulty. Once produced, most knowledge is free to all users and its producers cannot claim rewards for their effort---for example, the person who dreamed up the idea of using a wheel is long forgotten, and her heirs cannot even be identified, let alone make a claim to royalties.

Consider an oversimplified example where there are two types of capital, knowledge (type A) and other (type B) and where the producer of new knowledge can capture, through patent laws, secret production processes, and so forth, 30 percent of the income flow to society from the new capital. The private return---that is, the income flow capturable by the inventor---is given by the curve PMPA in Figure 2. Investors will accumulate new capital in the form which has the highest return to them. Thus, when the private capturable returns to investing in both types of capital are the same, the equilibrium quantity of A-capital will be KA0 and the real interest rate will be r0 which will be lower than the socially optimal rate, shown as re . Output will be below the maximum possible.

Capital can be misallocated in many other ways. The most frequent misallocation is between regions of the world. Though knowledge is freely available everywhere, the returns to specific applications of it in particular countries often can not be captured by individual investors because of government prohibitions, tariffs on necessary imports or other devices used by political interests who would be adversely affected by new technology or whose agenda would otherwise be derailed. This, in turn, will reduce the private relative to the social returns to accumulating various types of human capital. The returns to many forms of capital will thus differ across regions. World output would increase if capital could be reallocated to eliminate these differences.

The other dimension of economic growth is, of course, the growth of population. Per capita income depends on the level of aggregate income (which depends on the size of the capital stock) and on the size of the population. The bigger the population, the lower will be per capita income. We thus need to think about the factors that determine population growth.

Population growth obviously depends on family size---if every family has two children (who both live to maturity) the population will be constant. Parents will choose the size of their family based on costs and returns. In primitive societies, where all human capital is acquired naturally as adulthood is achieved, with no formal education, children are assets that produce more than their subsistence. Families have an incentive to produce as many children as possible. In advanced societies, formal education and other investment in children's human capital is necessary and must be paid for by sacrificing parent's and existing children's consumption or by reducing the number of children. Parents thus have a three-dimensional choice---how much to consume themselves, how much to invest in their children's human capital, and how many children to produce. Expansion in one dimension necessitates contraction in one or both of the other dimensions.

Growth of per capita income thus involves a choice of how much capital per person to pass on to the next generation. This depends on total capital accumulation for the benefit of heirs, and the number of children or heirs that will share that capital. And, of course, to get maximum effect the capital must be optimally allocated among capital types and among regions of the world.

If an appropriate institutional framework is not present to permit individuals to maintain ownership over their capital and capture the social returns to it, investment can be reduced to the point where per capita income growth grinds to a halt.

It is time for a test. Make sure to think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson