A devaluation of the official exchange rate operates like a

tariff---it shifts world demand for goods and services off of

foreign and onto domestic output. An increase in the official

parity value of the currency---an appreciation or revaluation---has

the opposite effect.

Let us look again at the goods and asset market equilibrium conditions of

the small open economy:

1. Y

= ( a + δ

+ ΦBT + DSB)/(s + m)

− μ/(s + m) r

+ m*/(s + m) Y*

− σ/(s + m) Q

2. r*

= − (1/θ)( M/P + ΦM )

− τ + (ε/θ) Y

where Y and Y* denote domestic and foreign output and

income and employment, ΦBT represents exogenous

shocks to the balance of trade, DSB is the debt service balance,

Q is the real exchange rate, defined as the relative price of

domestic in terms of rest-of-world output, r* is the domestic real

interest rate which, is determined by world market conditions, s

is the domestic marginal propensity to save, m and m*

are the domestic and foreign marginal propensities to import, M is

the nominal money stock, P is the domestic price

level, ΦM represents an exogenous shift factor in

the demand for real money balances and τ is the expected rate

of domestic inflation.

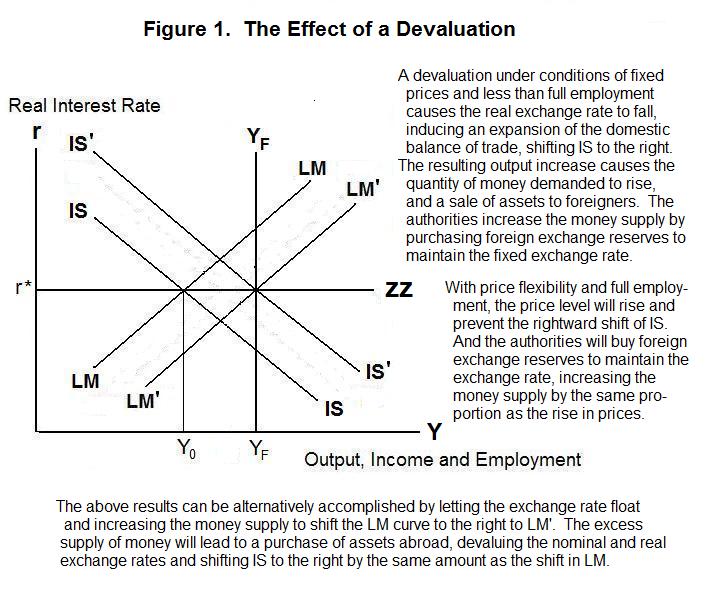

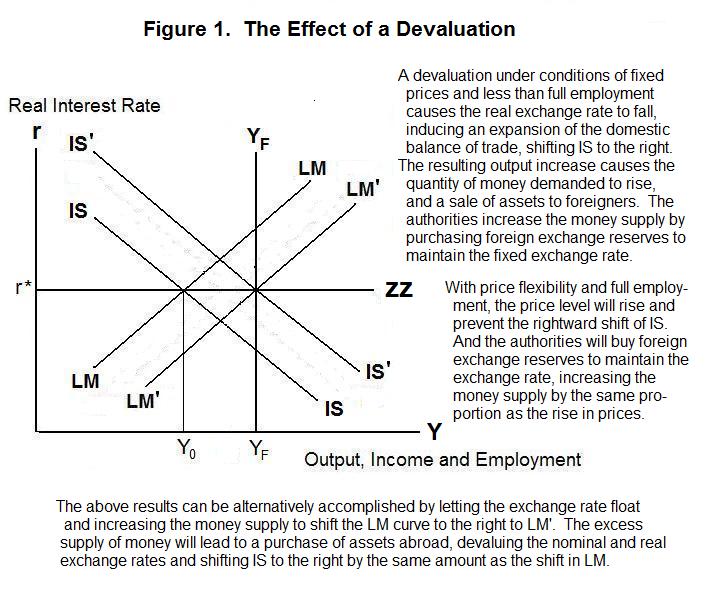

A devaluation of the official exchange rate under conditions of less than

full employment lowers Q in Equation 1, making domestic

goods cheaper in world markets. The current account balance increases,

increasing aggregate demand and shifting IS to the right. Given a fixed

exchange rate and less than full employment, small-open-economy equilibrium is

determined by the intersection of the IS curve and the ZZ line. The

rightward shift of the IS curve resulting from a devaluation of the nominal

exchange rate and corresponding reduction in Q leads to an

increase in output and employment. As output rises in Equation 2 at the

given world real interest rate, the quantity of money demanded increases

leading to a sale of assets abroad by domestic residents and an increase in

official reserve holdings as the authorities purchase the foreign exchange

necessary to keep the exchange rate from appreciating back to its old

level. This is shown in Figure 1. The LM curve shifts to pass through

the new IS-ZZ intersection, which happens here to be at the full-employment

level of output.

The adoption of a fixed exchange rate regime does not

mean that the exchange rate will never be changed. Changes in

official or parity exchange rates have typically been frequent.

Here we deal with the question of how output, employment, prices

and the balance of payments are affected when countries adjust

the level at which they fix their exchange rates.

These money supply and foreign exchange reserve adjustments can be seen more easily if we rewrite the asset Equation 2 in the form

3. M = P [ ΦM − θ (r* + τ) + ε Y ]

which puts M on the left-hand side.

Taking advantage of the fact that

4. H = mm H = mm (R + Dsc)

where H is the stock of base or high-powered money, mm is the money multiplier, R is the stock of foreign exchange reserves and Dsc is the domestic source component of the stock of base money, Equation 3 can be written

5. R = (P / mm) [ ΦM − θ (r* + τ) + ε Y ] − Dsc

The devaluation-induced rise in income leads to an increase in the demand for base money, given by the expression in the square brackets [..]. At a given level of Dsc , this results in an increase in the stock of official foreign exchange reserves.

A devaluation under less-than-full-employment conditions thus leads to an increase in output and employment and a one-shot increase in the stock of foreign exchange reserves. This increase in foreign exchange reserves would be avoided if the central bank were to increase Dsc appropriately by purchasing bonds in the open market.

It is sometimes argued that devaluations are necessary to eliminate deficits in the balance of payments. A balance of payments deficit is a continual outflow of foreign exchange reserves as indicated by a negative rate of change of R through time. For such a deficit to occur Dsc must be growing at a faster rate through time than the terms in the square brackets in Equation 5. A devaluation will increase the stock of reserves but not necessarily increase the rate of growth or reduce the rate of decline through time in that reserve stock. Thus, it will not necessarily cure a balance of payment deficit. A balance of payments deficit can be easily cured without changing the exchange rate by simply reducing the rate at which Dsc is growing through time. Also, a one-shot increase in the stock of reserves can be brought about by a one-shot reduction in Dsc without changing the official rate of exchange of domestic for foreign currency. Since a devaluation is not necessary to improve the balance of payments, what would be its purpose?

One possible reason for devaluing the currency would be to expand output and employment in a recession. The problem is, however, that when all other countries maintain their fixed exchange rates this is a strict beggar-thy-neighbor policy---any gain in domestic output which occurs through an increase in the current account balance comes at the expense of employment and output in the rest of the world.

It turns out that, apart from fiscal policies, a devaluation (or appreciation) of the exchange rate parity is the only way a country can change its price level in a fixed-exchange-rate regime under full-employment conditions. As the devaluation shifts IS to the right the price level rises to shift it back to its intersection with the ZZ curve at output and income YF. The money supply must then be increased either by an open market purchase of domestic bonds or an accumulation of official foreign exchange reserves by the central bank to maintain the position of the LM curve through that same intersection. Similarly, an appreciation of the country's currency will lower the domestic price level. Money supply manipulation is not possible when the exchange rate does not change because the authorities are forced to provide domestic residents with their desired money holdings in order to prevent the exchange rate from moving off its parity. But the price level change consequent on a devaluation can be equally well achieved by increasing the money supply and letting the exchange rate float. Indeed, the same money supply change will be associated with a given movement in the exchange rate whether the money supply adjustment is exogenous (and the exchange rate adjusts endogenously) or the exchange rate adjustment is exogenous (and the money supply adjusts endogenously). The shifts in IS and LM curves are identical in the two cases.

When countries change their official exchange rates, they usually move them by several percentage points. Since an appreciation of the domestic currency by, say, 10 percent will lower the equilibrium domestic price level by the same percentage, it would seem that official exchange rate movements are a rather blunt instrument for manipulating the domestic price level. A better approach would probably be to let the exchange rate float and gradually change the rate of domestic monetary expansion.

Time for a test. Be sure and think up your own answers before looking at the ones provided.

Choose Another Topic in the Lesson.